Comprehensive Genome Sequencing Can Improve Cancer Outcomes

Researchers from St Jude Children’s Research Hospital have demonstrated the feasibility of comprehensive genomic sequencing for all paediatric cancer patients, which maximises the lifesaving potential of precision medicine.

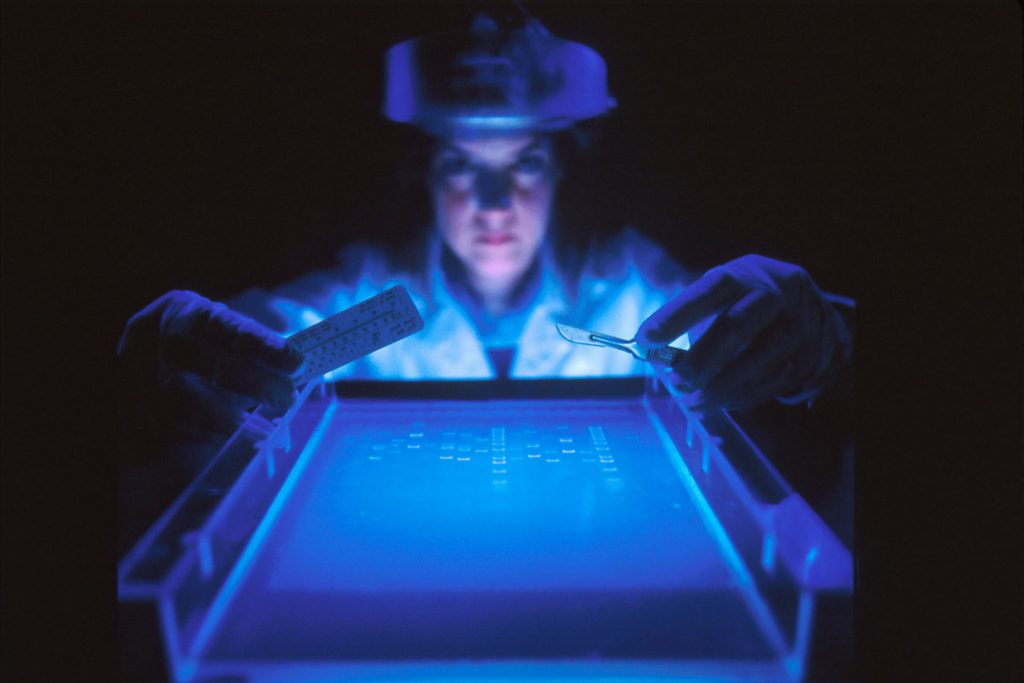

All 309 patients who enrolled in the study were offered whole genome and whole exome sequencing of germline DNA. For the 253 patients for whom adequate tumour samples were available, whole genome, whole exome and RNA sequencing of tumour DNA was carried out.

Overall, 86% of patients had at least one clinically significant variation in tumour or germline DNA. Those included variants related to diagnosis, prognosis, therapy or cancer predisposition. An estimated 1 in 5 patients had clinically relevant mutations that would not have been picked up with standard sequencing methods.

“Some of the most clinically relevant findings were only possible because the study combined whole genome sequencing with whole exome and RNA sequencing,” said Jinghui Zhang, PhD, St Jude Department of Computational Biology chair and co-corresponding author of the study.

While such comprehensive clinical sequencing is not widely available, as the technology becomes less expensive and accessible to more patients, comprehensive sequencing will become an important addition to paediatric cancer care.

“We want to change the thinking in the field,” said David Wheeler, PhD, St Jude Precision Genomics team director and a co-author of the study. “We showed the potential to use genomic data at the patient level. Even in common pediatric cancers, every tumor is unique, every patient is unique.

“This study showed the feasibility of identifying tumour vulnerabilities and learning to exploit them to improve patient care,” he said.

Tumour sequencing resulted in a change in treatment for 12 of the 78 study patients for whom standard of care was unsuccessful. In four of the 12 patients, the treatment changes stabilised disease and extended patient lives. Another patient, one with acute myeloid leukaemia, went into remission and was cured by blood stem cell transplantation.

“Through the comprehensive genomic testing in this study, we were able to clearly identify tumor variations that could be treated with targeted agents, opening doors for how oncologists manage their patients,” said co-corresponding author Kim Nichols, MD, St Jude Cancer Predisposition Division director.

The results of the study were published online in the journal Cancer Discovery.

Source: St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Journal information: Newman, S., et al (2021) Genomes for Kids: The scope of pathogenic mutations in pediatric cancer revealed by comprehensive DNA and RNA sequencing. Cancer Discovery. doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1631.