Elevated Cancer Risk in 9/11 Responders 20 Years On

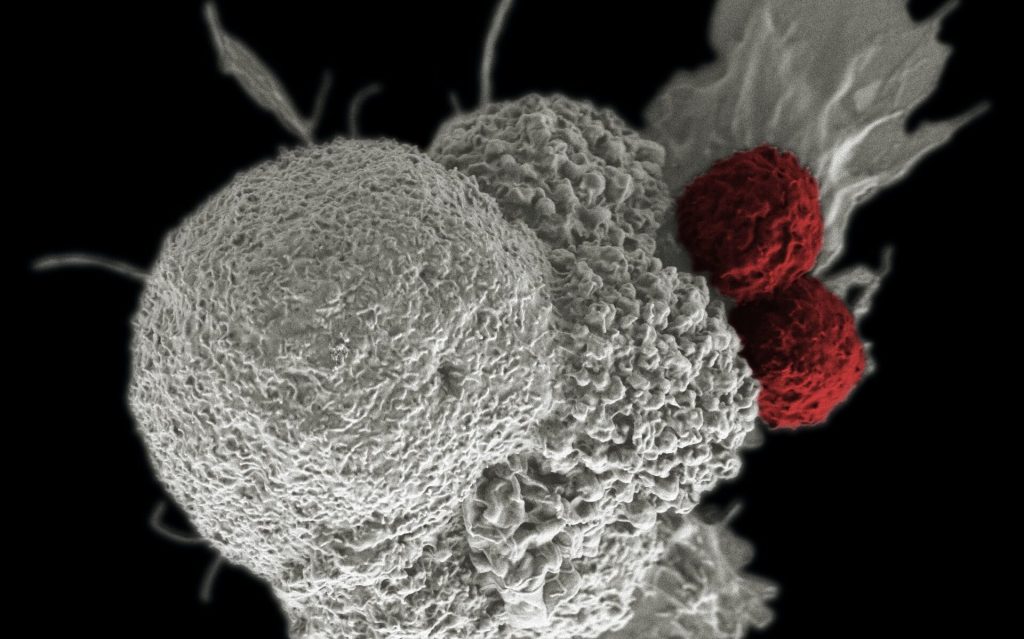

Associations between responders exposed to toxins at the World Trade Center (WTC) collapse site and increased cancer risk continue to be observed 20 years after the tragic event.

Thousands of rescue workers and first responders were exposed to toxins (asbestos, polychlorinated biphenyls, benzene, dioxins) in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2011. Two studies recently published in Occupational & Environmental Medicine reported on the cancer incidence rates among the WTC Health Program General Responder Cohort.

According to the first study, male New York City firefighters exposed to the WTC site had higher rates of all cancers 13% increase and a younger median age at diagnosis (55.6 vs 59.4 years) compared with male non-WTC-exposed firefighters.

The WTC-exposed firefighters had increased rates of a number of cancers, the highest of which was thyroid cancer (153%) reported Mayris Webber, DrPH, of the Bureau of Health Services at the Fire Department of the City of New York, and colleagues.

The second study from Charles Hall, PhD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, and colleagues, found that, beginning in 2007, rescue/recovery workers at the WTC site had a 24% increased risk for prostate cancer compared with the general population in New York State.

Webber and colleagues noted that all firefighters are repeatedly exposed to occupational hazards, including known carcinogens. Their 2016 study found no difference between WTC-exposed firefighters and a group of non-WTC-exposed firefighters from three other cities. The current study extended follow-up to allow for detection of cancers up to 15 years after WTC site exposure.

In this analysis of 10 786 WTC-exposed firefighters and 8813 non-WTC-exposed firefighters, prostate cancer was the most commonly diagnosed cancer among both groups.

In comparison to the US male population, all-cancer incidence among exposed firefighters was “higher than expected”, an increase of 9% even after adjustment for possible surveillance bias.

The researchers adjusted for earlier detection made possible through free screenings, but elevated rates persisted for all cancers (7%), prostate cancer (28%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (21%), and thyroid cancer (111%).

Webber and colleagues acknowledged that assessment of cancer risk among WTC-exposed firefighters is complex, as “these firefighters were subject to carcinogenic exposures, while also enduring enormous physical and mental burdens related to the attacks.”

“Evidence is slowly accruing about cancer and other long latency illnesses in relation to WTC exposure, although much remains to be determined,” they added.

Research has shown a lag of 10 to 20 years from exposure to a carcinogen to prostate cancer diagnosis. While WTC exposure was known to be linked to prostate cancer risk among responders, the length of time between exposure and cancer diagnosis was unknown.

Among the 54 394 rescue/recovery workers in the study, 1120 prostate cancer cases were diagnosed from 2002 to 2015.

The median time from the attacks to a diagnosis was 9.4 years, with the majority (66%) of cases diagnosed from 2009 to 2015.

Higher screening rates among first responders may have contributed to the increased incidence of prostate cancer seen in the study, the researchers acknowledged.

Comparing the responders who arrived earliest to the site with those who arrived later revealed a positive, monotonic, dose-response association with the early (2002-2006) and late (2007-2015) periods.

“The increased hazard among those who responded to the disaster earliest or were caught in the dust cloud suggests that a high intensity of exposure may have played some role in premature oncogenesis,” Hall and colleagues wrote. “Our findings support the need for continued research evaluating the burden of prostate cancer in WTC responders.”

Source: MedPage Today