FLASH Radiation Treatment for Tumours a Step Closer

Heavy ion bombardment in FLASH radiation treatment could be the future of radiotherapy, with encouraging findings from a German lab.

The GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung and the future accelerator centre FAIR succeeded in performing a carbon ion FLASH experiment for the first time in their Phase 0 experiment.

The scientists involved were able to achieve the very high dose rates required to irradiate tumours. The success was a collective effort of the GSI Biophysics Department and the accelerator crew on the GSI/FAIR campus in close collaboration with the German Cancer Research Center DKFZ and the Heidelberg Ion Therapy (HIT) center.

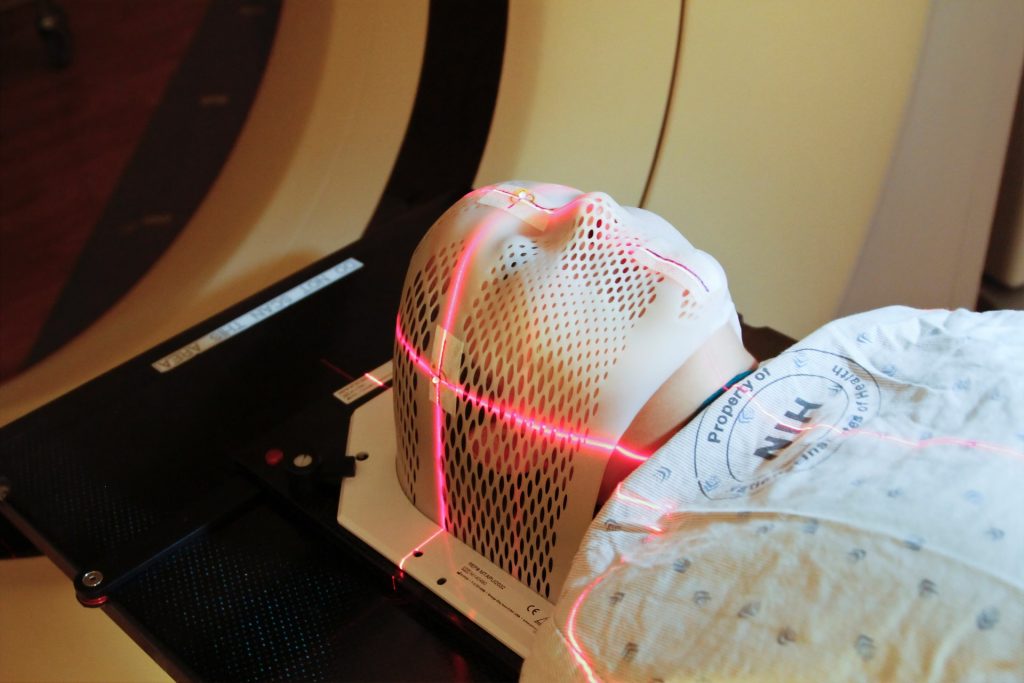

FLASH irradiation involves utra-short and ultra-high radiation, delivering the treatment dose in fractions of a second. Traditional radiation therapy, as well as proton or ion therapy, deliver smaller doses of radiation to a patient over an extended time period, whereas FLASH radiotherapy is thought to require only a few short irradiations, all lasting less than 100 milliseconds.

In the field of electron radiation, recent in vivo investigations have shown that the FLASH method’s ultra-high dose rate is less harmful to healthy tissue, but just as efficient as conventional dose-rate radiation to inhibit tumour growth. Such an effect has not yet been demonstrated for proton and for ion beam irradiation, which is the basis of the tumour therapy with carbon ions developed at GSI. There is still a lot of research to be done here. The results of the current experiment at GSI are now being evaluated and will contribute to new knowledge.

There have also been technical barriers to FLASH radiation. Until now, FLASH technique has only been applicable using electron and proton accelerators. While the required dose rates for electrons and protons can be achieved with a cyclotron (circular accelerator), this is more difficult with the synchrotrons required in heavy ion therapy, such as the SIS18 at GSI.

That is why the current FAIR Phase 0 experiment is a very crucial step: Thanks to the improvements at the existing GSI accelerator facility as part of the preparations for FAIR, the necessary dose rate in millisecond range can now also be achieved for carbon ions. However, much development work remains to be done before this procedure is mature enough to be routinely used on patients in the field of electron radiation.

Professor Marco Durante, Head of the GSI Biophysics Research Department, was very pleased with this important milestone in the development of FLASH irradiation:

“It is a forward-looking method that could significantly increase the therapeutic window in radiotherapy. I am very happy that the researchers and the accelerator team were able to demonstrate the possibility to create conditions with carbon beams that are necessary for FLASH therapy of tumors. If we can combine the great effect and precision of heavy ion therapy with FLASH irradiation while maintaining efficacy and causing little damage to healthy tissue, this could pave the way of a future radiation therapy several years from now.”

Professor Paolo Giubellino, The Scientific Managing Director of GSI and FAIR, expressed his delight at the results: “The combination of expertise in biophysics and medicine as well as engineering excellence allows the first world-class experiments FLASH irradiation with ion beams to be performed. This could result in important complements to existing radiation therapies. Applications in tumour therapy are one of the research areas that can benefit from the recent increased intensities of GSI accelerators. However, modern radiobiology will substantially benefit from beams with even higher intensities, such as we will have at the FAIR facility currently under construction. FLASH is a first example of these future directions of work”.