Rare Disease Sheds Light on a Side Effect of Immunotherapy

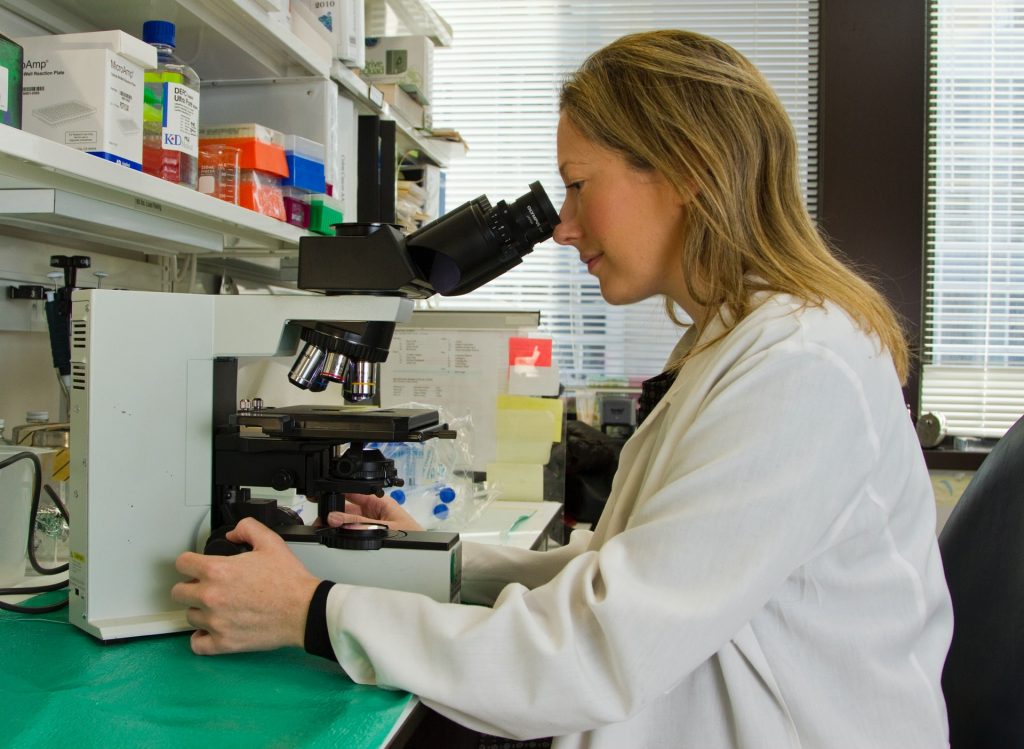

A multinational collaboration co-led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research has uncovered a potential explanation for why some cancer patients receiving a type of immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors experience increased susceptibility to common infections.

The findings, published in the journal Immunity, provide new insights into immune responses and reveal a potential approach to preventing the common cancer therapy side effect.

“Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies have revolutionised cancer treatment by allowing T cells to attack tumours and cancer cells more effectively. But this hasn’t been without side effects – one of which is that approximately 20% of cancer patients undergoing checkpoint inhibitor treatment experience an increased incidence of infections, a phenomenon that was previously poorly understood,” says Professor Stuart Tangye, co-senior author of the study and Head of the Immunology and Immunodeficiency Lab at Garvan.

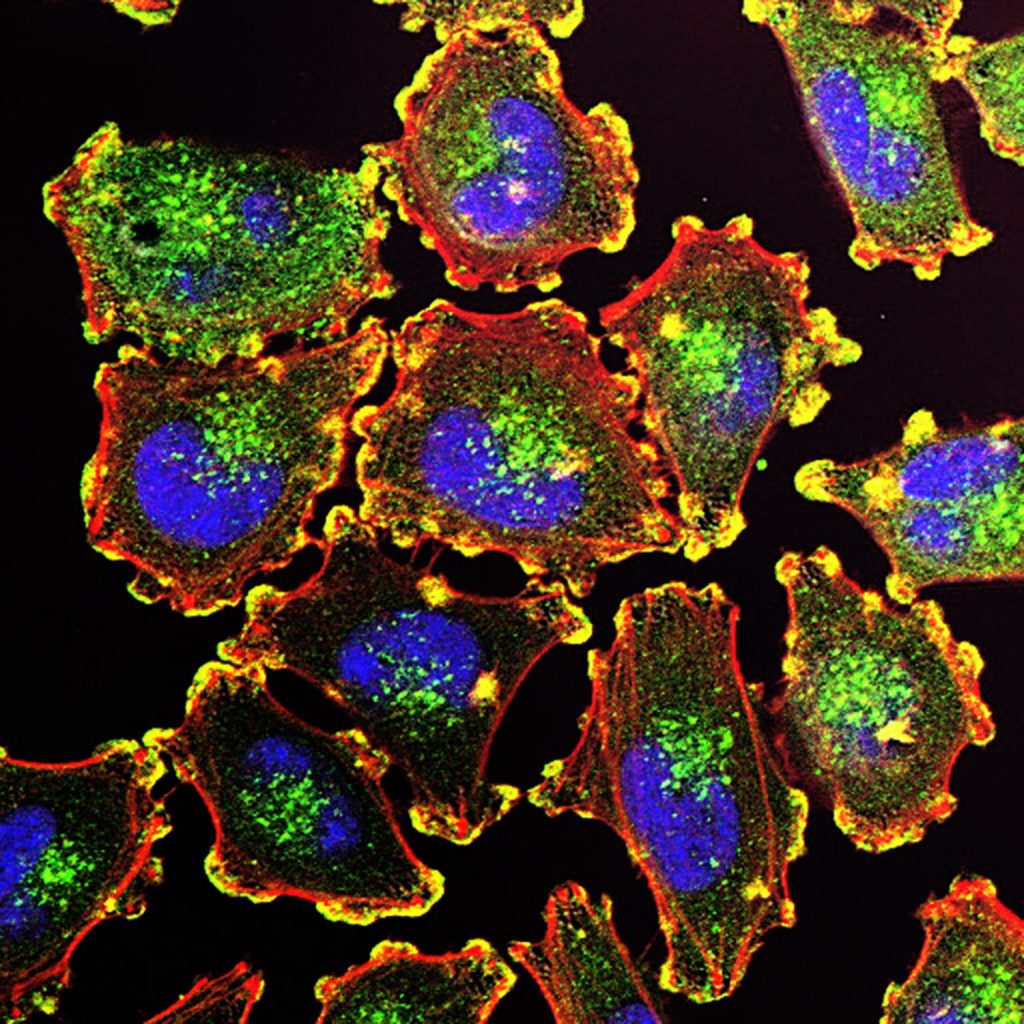

“Our findings indicate that while checkpoint inhibitors boost anti-cancer immunity, they can also handicap B cells, which are the cells of the immune system that produce antibodies to protect against common infections. This understanding is a critical first step in understanding and reducing the side effects of this cancer treatment on immunity.”

Insights to improve immunotherapy

The researchers focused on the molecule PD-1, which acts as a ‘handbrake’ on the immune system, preventing overactivation of T cells. Checkpoint inhibitor therapies work by releasing this molecular ‘handbrake’ to enhance the immune system’s ability to fight cancer.

The study, which was conducted in collaboration with Rockefeller University in the USA and Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan, examined the immune cells of patients with rare cases of genetic deficiency of PD-1, or its binding partner PD-L1, as well as animal models lacking PD-1 signalling. The researchers found that impaired or absent PD-1 activity can significantly reduce the diversity and quality of antibodies produced by memory B cells – the long-lived immune cells that ‘remember’ past infections.

“We found that people born with a deficiency in PD-1 or PD-L1 have reduced diversity in their antibodies and fewer memory B cells, which made it harder to generate high-quality antibodies against common pathogens such as viruses and bacteria,” says Dr Masato Ogishi, first author of the study, from Rockefeller University.

Professor Tangye adds: “This dampening of the generation and quality of memory B cells could explain the increased rates of infection reported in patients with cancer receiving checkpoint inhibitor therapy.”

Co-author Dr Kenji Chamoto, from Kyoto University, says, “PD-1 inhibition has a ‘yin and yang’ nature: it activates anti-tumour immunity but at the same time impedes B-cell immunity. And this duality seems to stem from a conserved mechanism of immune homeostasis.”

New recommendation for clinicians

The researchers say the findings highlight the need for clinicians to monitor B cell function in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors and point to preventative interventions for those at higher risk of infections.

Co-senior author Dr Stéphanie Boisson-Dupuis, from Rockefeller University, says, “Although PD-1 inhibitors have greatly improved cancer care, our findings indicate that clinicians need to be aware of the potential trade-off between enhanced anti-tumour immunity and impaired antibody-mediated immunity.”

“One potential preventative solution is immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IgRT), an existing treatment used to replace missing antibodies in patients with immunodeficiencies, which could be considered as a preventative measure for cancer patients at higher risk of infections,” she says.

From rare cases to insights to benefit all

“Studying cases of rare genetic conditions such as PD-1 or PD-L1 deficiency enables us to gain profound insights into how the human immune system normally works, and how our own manipulation of it can affect it. Thanks to these patients, we’ve found an avenue for fine-tuning cancer immunotherapies to maximise benefit while minimising harm,” says Professor Tangye.

Looking ahead, the researchers will explore ways to refine checkpoint inhibitor treatments to maintain their powerful anti-cancer effects while preserving the immune system’s ability to fight infections.

“This research highlights the potential for cancer, genomics and immunology research to inform one another, enabling discoveries that can benefit the broader population,” says Professor Tangye.

Professor Stuart Tangye is a Conjoint Professor at St Vincent’s Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, UNSW Sydney.