A New Way to Kill Cancer Cells via Ferroptosis

In a first, a team in Germany has produced a substance capable of sending cancer cells into ferroptosis, a form of cell death discovered only in recent years. This could pave the way for the development of new drugs.

Conventional cancer drugs work by triggering apoptosis, that is programmed cell death, in tumour cells. However, tumour cells have the ability to develop strategies to escape apoptosis, rendering the drugs ineffective. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, a research team from Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, describes a new mechanism of action that kills cancer cells through ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is another form of programmed cell death that wasn’t discovered until the 2010s. The Bochum group synthesised a metal complex, demonstrated its effectiveness in cell cultures and on microtumours and identified the chemical processes underlying the mechanism of action.

Two types of programmed cell death

In programmed cell death, certain signaling molecules initiate a kind of suicide program to cause cells to die in a controlled manner. This is an essential step to eliminate damaged cells or to control the number of cells in certain tissues, for example. Apoptosis has long been known as a mechanism for programmed cell death. Ferroptosis is another mechanism that has recently been discovered which, in contrast to other cell death mechanisms, is characterised by the accumulation of lipid peroxides. This process is typically catalysed by iron which is where the name ferroptosis derives from.

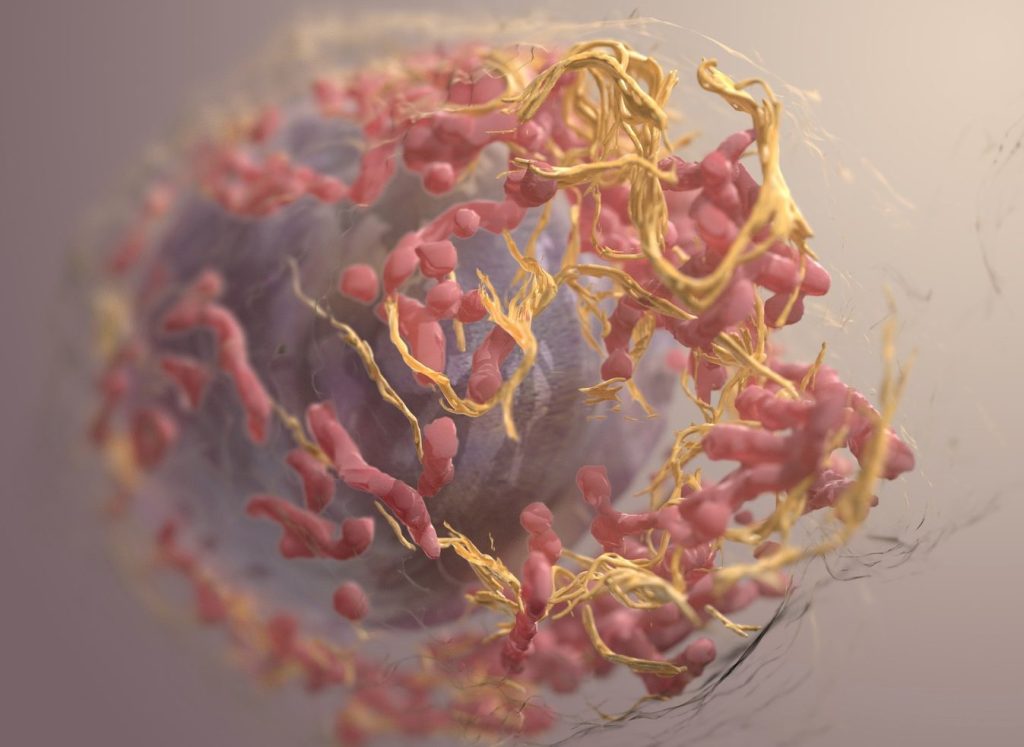

“Searching for an alternative to the mechanism of action of conventional chemotherapeutic agents, we specifically looked for a substance capable of triggering ferroptosis,” explains Johannes Karges. His group synthesized a cobalt-containing metal complex that accumulates in the mitochondria of cells and generates reactive oxygen species, more precisely hydroxide radicals. These radicals attack polyunsaturated fatty acids, resulting in the formation of large quantities of lipid peroxides, which in turn trigger ferroptosis. The team was thus the first to produce a cobalt complex designed to specifically trigger ferroptosis.

Effectiveness demonstrated on artificial microtumours

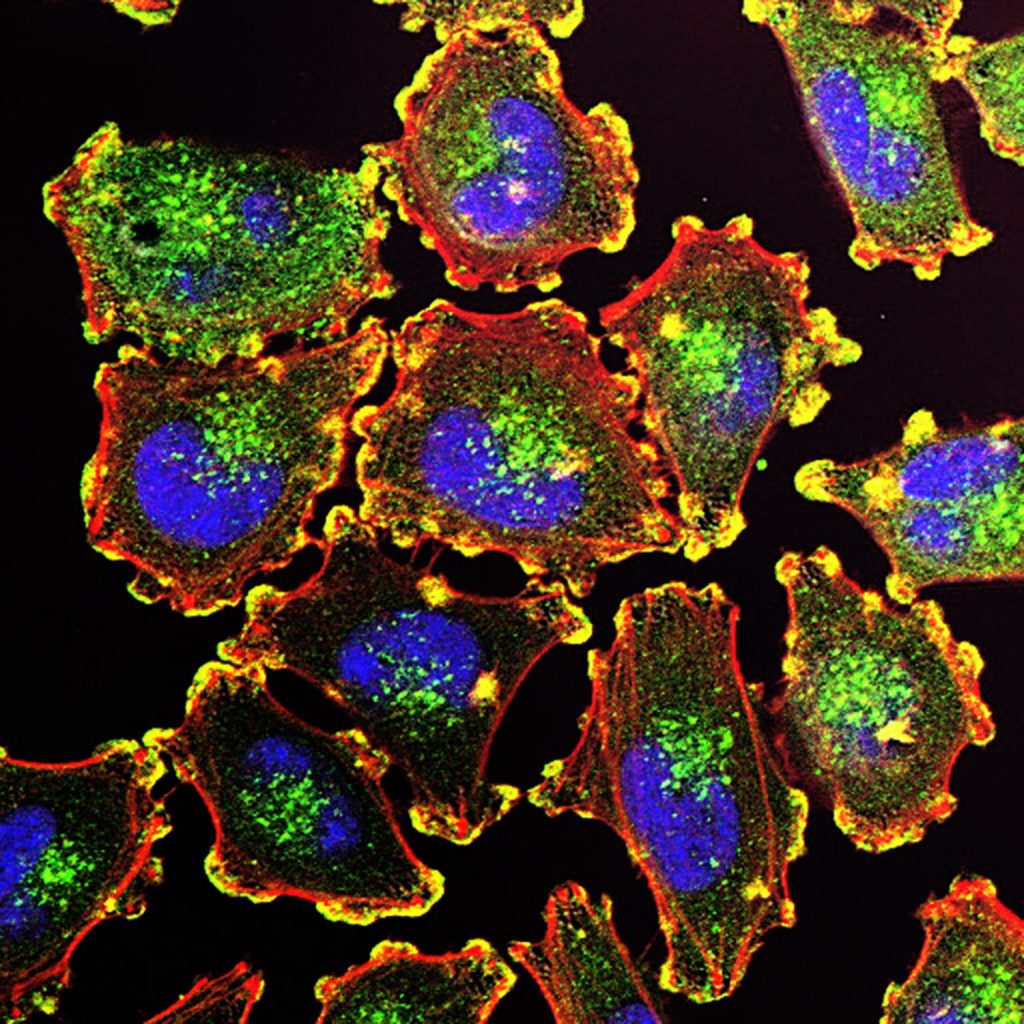

The researchers from Bochum used a variety of cancer cell lines to show that the cobalt complex induces ferroptosis in tumour cells. On top of that, the substance slowed down the growth of artificially produced microtumours .

“We are confident that the development of metal complexes that trigger ferroptosis is a promising new approach for cancer treatment,” as Johannes Karges sums up the research, adding: “However, there’s still a long way to go before our studies result in a drug.” The metal complex must first prove effective in animal studies and clinical trials. What’s more, the substance doesn’t currently selectively target tumour cells, but would also attack healthy cells. This means that researchers must first find a way to package the cobalt complex in such a way that it damages nothing but tumour cells.

Source: Ruhr-University Bochum