‘Ultra-rapid’ Testing for Cancer Genes in the Operating Theatre

A novel tool for rapidly identifying the genetic “fingerprints” of cancer cells may enable future surgeons to more accurately remove brain tumours while a patient is in the operating room, new research reveals. Many cancer types can be identified by certain mutations, changes in the instructions encoded in the DNA of the abnormal cells.

Led by a research team from NYU Langone Health, the new study describes the development of Ultra-Rapid droplet digital PCR, or UR-ddPCR, which the team found can measure the level of tumour cells in a tissue sample in only 15 minutes while also being able to detect small numbers of cancer cells (as few as five cells/mm2).

The researchers say their tool is fast and accurate enough, at least in initial tests on brain tissue samples, to become the first practical tool of its kind for detecting cancer cells directly using mutations in real time during brain surgery.

The researchers showed that UR-ddPCR had markedly faster processing speed than standard droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR). Standard ddPCR can accurately quantify tumor cells, but it typically takes several hours to produce a result, making it impractical as a surgical guide.

“For many cancers, such as tumors in the brain, the success of cancer surgery and preventing the cancer’s return is predicated on removing as much of the tumor and surrounding cancer cells as is safely possible,” said study co-senior study investigator and neurosurgeon Daniel A. Orringer, MD.

“With Ultra-Rapid droplet digital PCR, surgeons may now be able to determine what cells are cancerous and how many of these cancer cells are present in any particular tissue region at a level of accuracy that has never before been possible,” said Dr Orringer.

Published in the journal Med, the study showed that UR-ddPCR produced the same results as standard ddPCR and genetic sequencing in more than 75 tissue samples from 22 patients at NYU Langone undergoing surgery to remove glioma tumours. Results from UR-ddPCR were also checked against known samples with cancer cells and samples without any cancer.

“Our study shows that Ultra-Rapid droplet digital PCR could be a fast and efficient tool for making a molecular diagnosis during surgery for brain cancer, and it has potential to also be used for cancers outside the brain,” said senior study investigator Gilad Evrony, MD, PhD.

To develop UR-ddPCR, researchers looked for efficiencies in each of the steps involved in standard ddPCR. The team shortened the time needed to extract DNA from tumour samples from 30 minutes to less than 5 minutes in a manner that is still compatible with subsequent ddPCR. The researchers also found efficiencies by increasing the concentrations of the chemicals used in testing, reducing the overall time needed for some steps from two hours to less than three minutes. Time savings were also achieved by using reaction vessels prewarmed to each of the two temperatures required by the PCR rather than repeatedly cycling the temperature of a single reaction vessel between two temperatures.

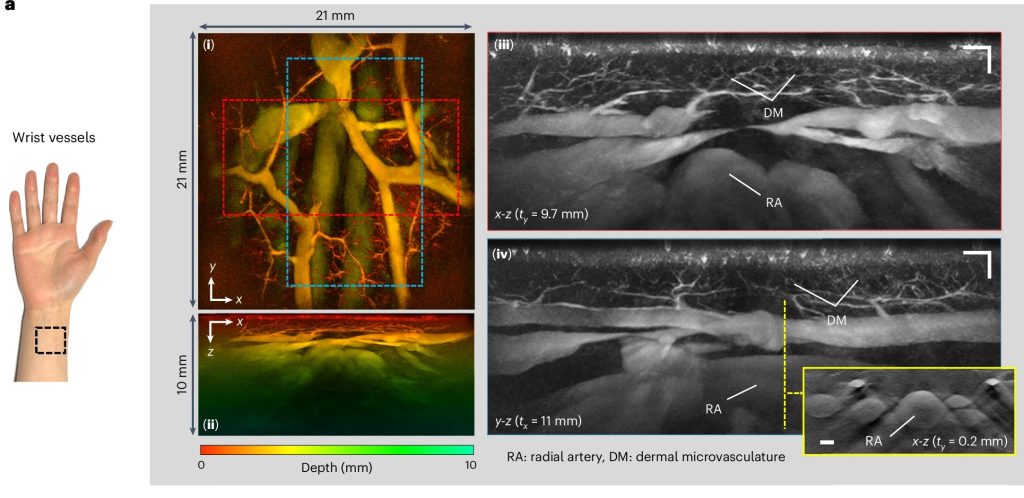

For the study, researchers used UR-ddPCR to measure the levels of two genetic mutations, IDH1 R132H and BRAF V600E, which are prevalent in brain cancers. They combined UR-ddPCR with another technique the researchers developed earlier, called stimulated Raman histology, to calculate both the fraction and the density of tumour cells within each tissue sample.

Researchers caution that widespread use of the tool awaits further refinements and clinical trials. They say their next step is to automate UR-ddPCR to make it faster and simpler to use in the operating room. Subsequent clinical trials will be necessary to compare patient outcomes using their tool compared to current diagnostic technologies. They also plan to develop the technology to identify other common genetic mutations for other cancer types.

Source: NYU Langone Health / NYU Grossman School of Medicine