Immune Cell Networks Found to be Driving Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Rutgers Health researchers have discovered that networks of misplaced immune cells drive an aggressive lung disease, potentially opening a path to new treatments for a condition that kills 80% of patients within a decade.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) scars lung tissue and makes breathing increasingly difficult until patients can’t get enough oxygen. Available drugs provide minimal benefit. Lung transplantation works for some patients, but transplants have a 50% five-year mortality rate.

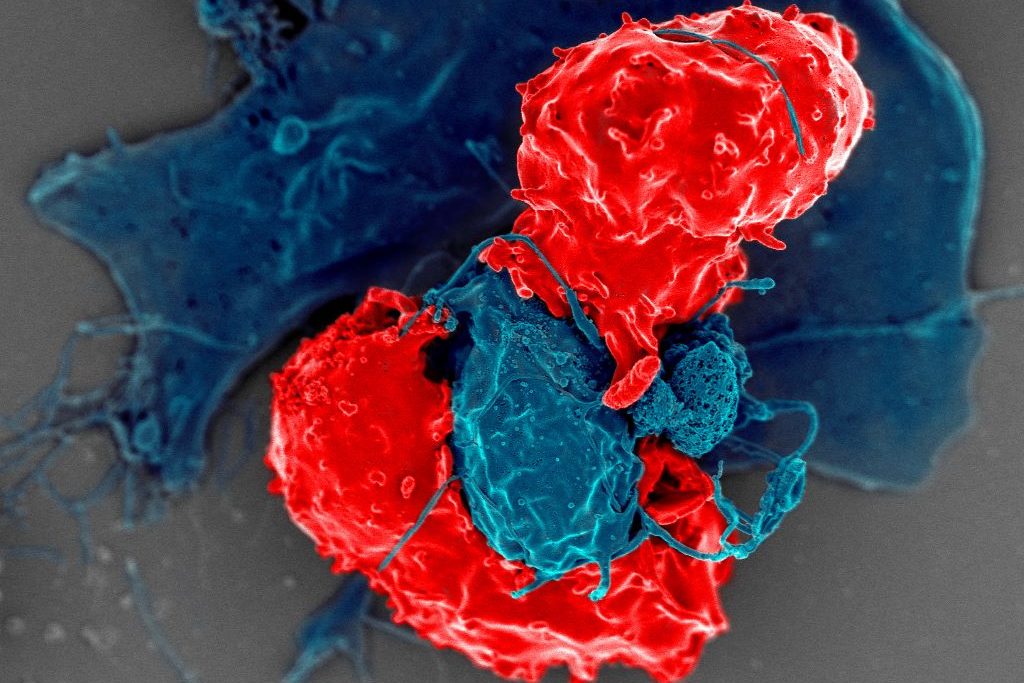

This study in the European Respiratory Journal used advanced spatial mapping techniques to compare healthy lung tissues and tissues from patients with fatal IPF. The researchers discovered that disease-scarred lung tissue abounds in plasma cells – specialised immune cells that typically reside in bone marrow and produce antibodies.

“What we found most striking in this study is that all the fibrotic regions of IPF patients’ lungs are covered by antibody-producing plasma cells,” Qi Yang, an associate paediatrics professor at Rutgers and a senior author of the study. “In normal lungs, there are almost no plasma cells. But in IPF patients, the lungs are full of them.”

The researchers identified previously unknown cellular networks orchestrating this abnormal immune response. They discovered novel mural cells wrapping around blood vessels and producing signal proteins that organize immune responses. They also found unique fibroblasts secreting a protein that attracts plasma cells to damaged areas.

“This particular type of fibroblast has never been described before,” said Reynold Panettieri, director of the Rutgers Institute for Translational Medicine and Science and a senior author of the study. “People have shown that fibroblasts are the cell types responsible for scarring – in the skin, the lungs and the brain – but this particular type of fibroblast seems unique to the lung.”

Having found the plasma cells in lung tissue taken from people who died of IPF, the team began using live mice to see if reducing plasma in the lungs slowed disease formation. This work demonstrated that blocking signaling pathways reduced plasma cell accumulation and alleviated lung scarring. Targeting these same signaling pathways may thus prove an effective disease treatment in humans, the researchers said.

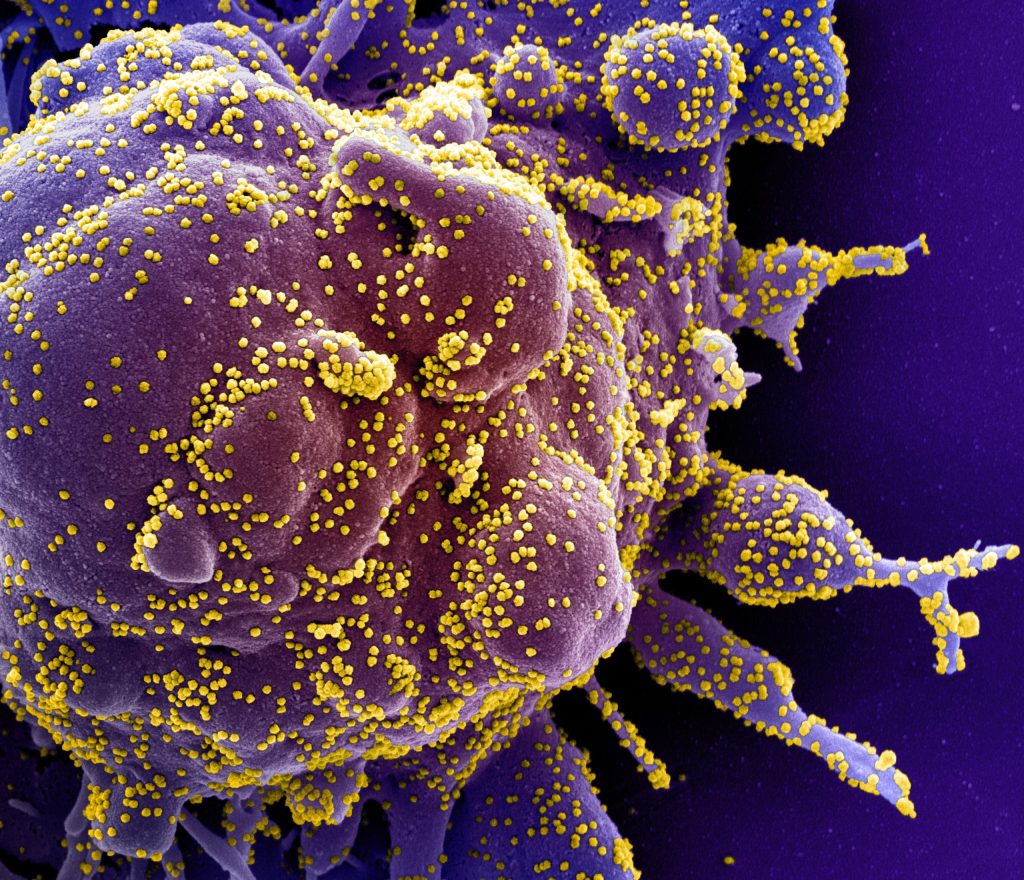

The research is particularly promising because drugs targeting plasma cells already exist. Medications used to treat multiple myeloma, a plasma cell cancer, could potentially be repurposed to treat IPF.

“If the plasma cells are really making the bad antibodies, I assume we may have to get rid of them,” said Yang, a member of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Science. “Otherwise, patients will keep making these antibodies that drive the disease.”

Previous studies have shown that IPF patients have heightened antibody responses and elevated lung antibody levels. The new research explains the origin of these antibodies and reveals how abnormal antibody-producing cells accumulate in the lungs.

The researchers said the antibodies may drive tissue damage through several mechanisms. Their data suggest that antibody-antigen complexes stimulate the production of transforming growth factor-beta from pulmonary macrophages, thus promoting fibrosis.

“Now that we have a target, a cell, a unique cell that Dr Yang has identified and phenotyped, we’re optimistic that we could affect that cell and not other fibroblasts that are important in normal injury repair response,” Panettieri said.

For patients with IPF, the findings offer hope of new treatments for a debilitating condition with limited therapeutic options. The disease typically affects men over 60 years of age, with most patients dying within five years of diagnosis.

The next steps for the research team include determining whether the plasma cells are producing autoantibodies against healthy tissues and further investigating how fibroblasts and mural cells develop their abnormal properties in IPF.

“Our research suggests that IPF might have a strong autoimmune link,” Yang said.

Source: Rutgers University