Survey Sheds Light on the Phenomenon of Topical Steroid Withdrawal

Painful skin and trouble sleeping are among the problems reported when tapering cortisone cream for atopic eczema, as shown by a study headed by the University of Gothenburg. Many users consider the problems to be caused by cortisone dependence.

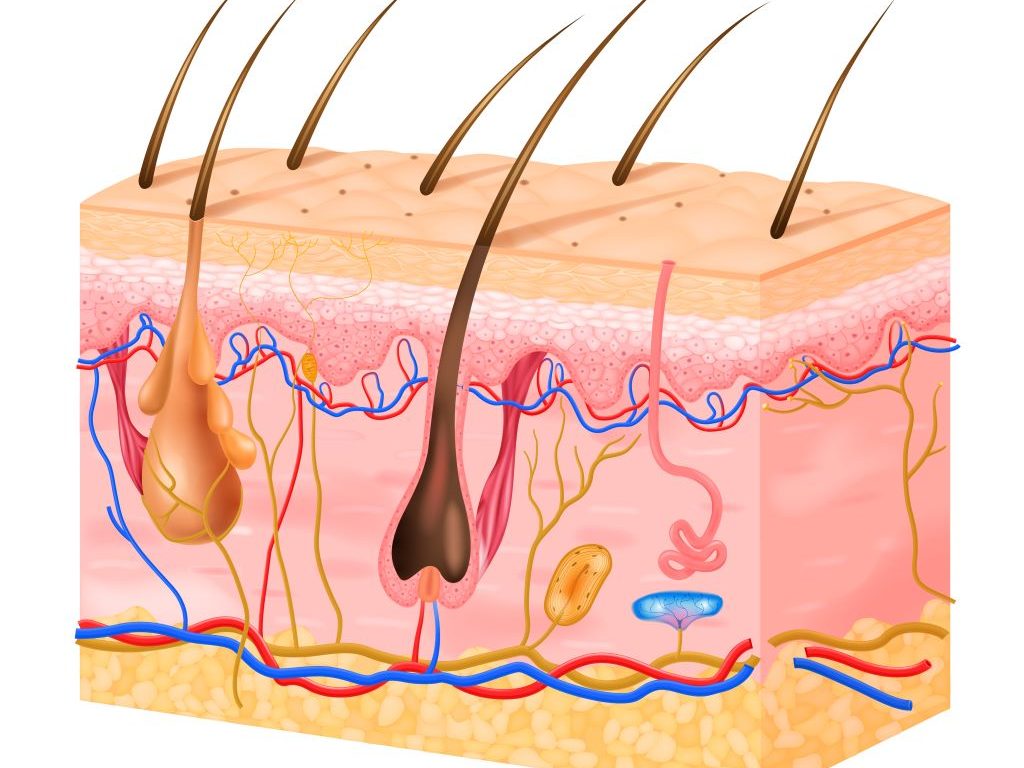

Topical steroid withdrawal (TSW) is a phenomenon commonly described as extremely red and painful skin arising when cortisone cream treatment is tapered or stopped.

While TSW is not an established diagnosis, the name indicates that the skin has become dependent on cortisone. Little research has been conducted to identify a dependency mechanism, so scientific support is lacking. At the same time, the term has become commonplace on social media, raising concerns among patients about cortisone cream safety.

Now, a national research group in Sweden, headed by Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, has conducted the first study in which a larger group has been asked to provide a detailed account of what they consider to be TSW. The results are published in the journal Acta Dermato-Venereologica.

Questionnaire via social media

The study targeted adults with atopic eczema, a group that often uses cortisone cream, who also identified as suffering from TSW. The study was conducted by means of an anonymous questionnaire presented in Swedish in social media forums, with the option to share a link to invite other potential participants. The questionnaire was answered by almost one hundred people aged 18–39, the majority of whom were women.

“We wanted to gain more knowledge about how those who identify as suffering from TSW define the phenomenon and which symptoms they describe,” says Mikael Alsterholm, a researcher at the University of Gothenburg and a senior consultant in dermatology and venereology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

The results show variations in how the participants defined TSW. Most common was to define it as a dependence on cortisone, with symptoms arising when tapering or stopping its use, although many others also defined TSW as a reaction to cortisone already during its use.

It was also common to define TSW on the basis of the symptoms seen in the skin, such as redness and pain. While the symptoms described varied, they were largely similar to the symptoms seen in an exacerbation of atopic eczema.

In addition to the skin becoming red, dry, and blistered – mainly on the face, neck, torso, and arms – the participants also described sleep problems due to itching as well as signs of anxiety and depression.

Healthcare and research involvement

A majority of the participants described concurrent symptoms of both atopic eczema and TSW. Cortisone cream was most often cited as the triggering factor, while some cited cortisone tablets and a few cortisone-free treatments.

“It’s important that healthcare professionals and researchers are involved in the discussion on TSW and contribute science-based knowledge where possible. Cortisone cream is an effective and safe treatment for most people, and at present there’s no support for avoiding its use for fear of the types of symptoms described in the context of TSW,” says Mikael Alsterholm.

“At the same time, there’s a patient group with different experiences, expressed as TSW, and their symptoms and the potential causes need to be investigated by means of both research and practical healthcare. To do this, we first need to define TSW. While we understand that this is complicated, we hope that this study can help establish such a definition,” he concludes.

Source: University of Gothenburg