Scientists Discover How Aspirin Could Prevent Metastasis in Some Cancers

Scientists have uncovered the mechanism behind how aspirin could reduce the metastasis of some cancers by stimulating the immune system.

In the study published in Nature, the scientists say that discovering the mechanism will support ongoing clinical trials, and could lead to the targeted use of aspirin to prevent the spread of susceptible types of cancer and the development of more effective drugs to prevent cancer metastasis.

The scientists caution that aspirin can have serious side effects and that trials are underway to establish safety and efficacy.

A reduction in the spread of some cancers

Studies of people with cancer have previously observed that those taking daily low-dose aspirin have a reduction in the spread of some cancers, such as breast, bowel, and prostate cancers, leading to ongoing clinical trials. However, until now it wasn’t known exactly how aspirin could prevent metastases.

In this study, led by researchers at the University of Cambridge, the scientists say their discovery of how aspirin reduces cancer metastasis was serendipitous.

They were investigating the process of metastasis, because, while cancer starts out in one location, 90% of cancer deaths occur when cancer spreads to other parts of the body.

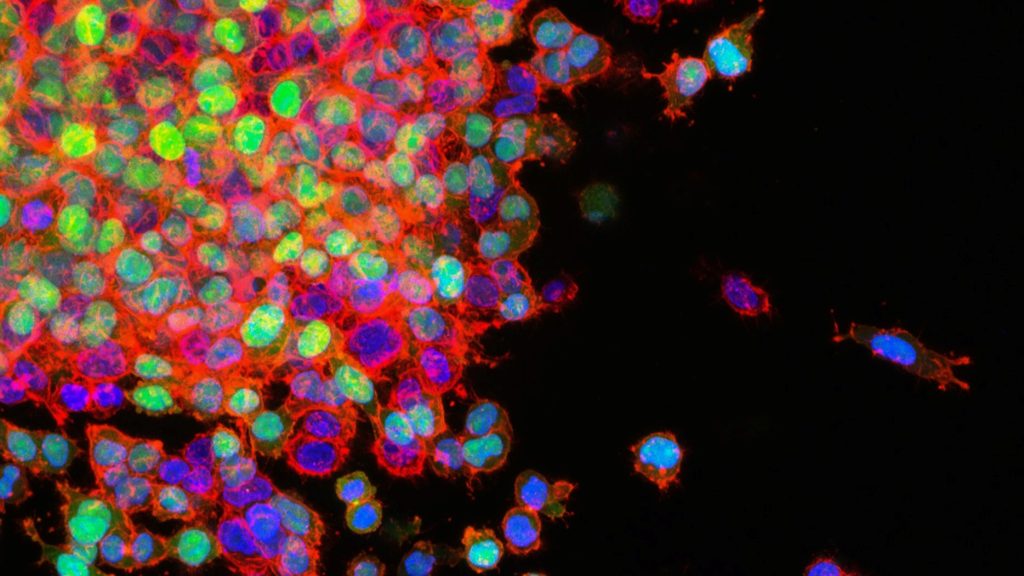

The scientists wanted to better understand how the immune system responds to metastasis. This is because when individual cancer cells break away from their originating tumour and spread to another part of the body, they are particularly vulnerable to immune attack.

An effect on cancer metastasis

The immune system can recognise and kill these lone cancer cells more effectively than cancer cells within larger originating tumours, which have often developed an environment that suppresses the immune system.

The researchers previously screened 810 genes in mice and found 15 that had an effect on cancer metastasis. In particular, they found that mice lacking a gene that produces a protein called ARHGEF1 had less metastasis of various primary cancers to the lungs and liver.

The researchers determined that ARHGEF1 suppresses T cells, which can recognise and kill metastatic cancer cells.

To find a suitable drug, the scientists traced signals in the cell to determine that ARHGEF1 is switched on when T cells are exposed to a clotting factor called thromboxane A2 (TXA2).

This was an unexpected revelation for the scientists, because TXA2 is already well-known and linked to how aspirin works.

Reduces the production of TXA2

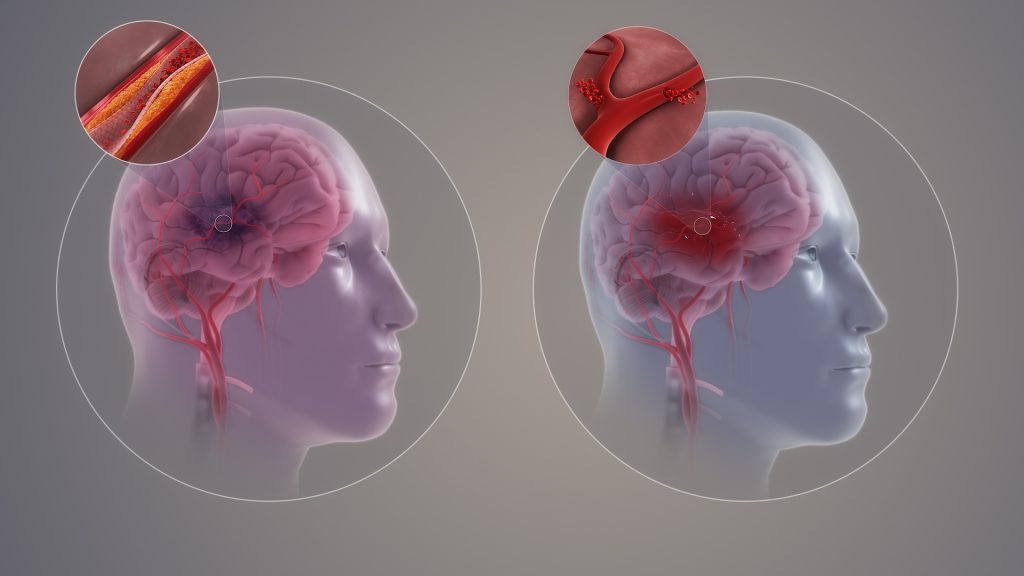

TXA2 is produced by platelets; aspirin reduces the production of TXA2, leading to the anti-clotting effects, which underlies its ability to prevent heart attacks and strokes.

This new research found that aspirin prevents cancers from spreading by decreasing TXA2 and releasing T cells from suppression. They used a mouse model of melanoma to show that in mice given aspirin, the frequency of metastases was reduced compared to control mice, and this was dependent on releasing T cells from suppression by TXA2.

Professor Rahul Roychoudhuri, from the University of Cambridge, who led the study, said:

Despite advances in cancer treatment, many patients with early stage cancers receive treatments, such as surgical removal of the tumour, which have the potential to be curative, but later relapse due to the eventual growth of micrometastases – cancer cells that have seeded other parts of the body but remain in a latent state.

Most immunotherapies are developed to treat patients with established metastatic cancer, but when cancer first spreads there’s a unique therapeutic window of opportunity when cancer cells are particularly vulnerable to immune attack.

We hope that therapies that target this window of vulnerability will have tremendous scope in preventing recurrence in patients with early cancer at risk of recurrence.

More accessible globally

Dr Jie Yang, who carried out the research, at the University of Cambridge, said:

It was a Eureka moment when we found TXA2 was the molecular signal that activates this suppressive effect on T cells.

Before this, we had not been aware of the implication of our findings in understanding the anti-metastatic activity of aspirin. It was an entirely unexpected finding which sent us down quite a different path of enquiry than we had anticipated.

Aspirin, or other drugs that could target this pathway, have the potential to be less expensive than antibody-based therapies, and therefore more accessible globally.

In the future, the researchers plan to help the translation of their work into potential clinical practice by collaborating with Professor Ruth Langley, of the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, who is leading the Add-Aspirin clinical trial, to find out if aspirin can stop or delay early stage cancers from coming back.

Caution on aspirin use

Professor Langley, who was not involved in this study, commented:

This is an important discovery. It will enable us to interpret the results of ongoing clinical trials and work out who is most likely to benefit from aspirin after a cancer diagnosis.

In a small proportion of people, aspirin can cause serious side-effects, including bleeding or stomach ulcers. Therefore, it is important to understand which people with cancer are likely to benefit and always talk to your doctor before starting aspirin.

Source: UK Research and Innovation