Heparin-induced Thrombocytopenia is Caused by a Single Antibody

Researchers at McMaster University have discovered that a rare but dangerous reaction to heparin is caused by a single antibody – overturning decades of medical misunderstanding and opening the door to more precise ways of diagnosing and treating this medical complication.

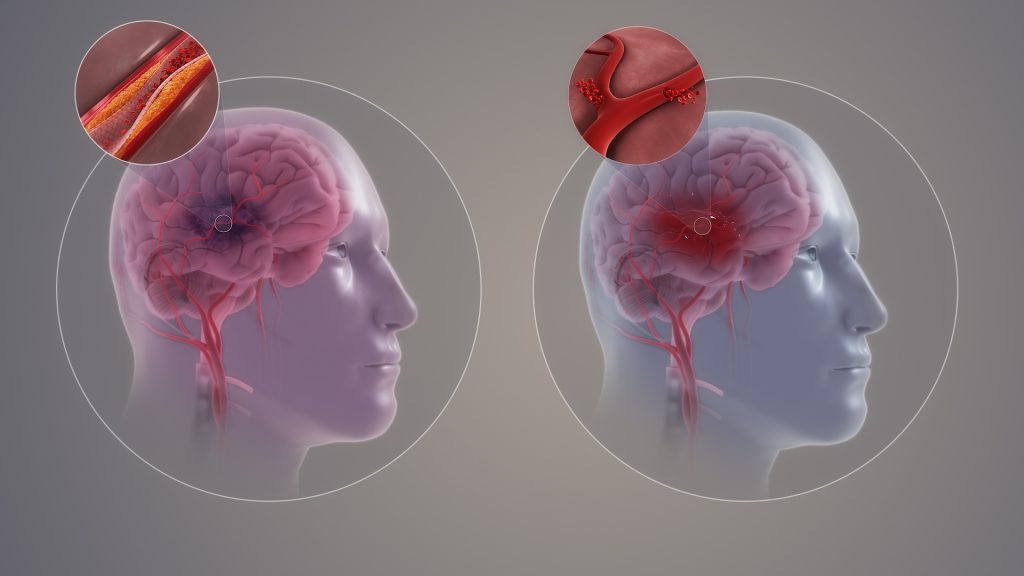

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, focused on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), a serious immune complication that affects approximately one per cent of hospitalised patients treated with the blood thinner heparin. Nearly half of those who develop HIT experience life-threatening blood clots, which can lead to strokes, heart attacks, amputations, and even death, making early detection and treatment critically important.

Until now, scientists believed that the immune response causing HIT involved many different types of antibodies working together. But this research has revealed something surprising: in every patient studied, only one antibody was causing the disease, while the rest created what the researchers describe as a kind of “smokescreen,” making it harder to identify the true culprit. This discovery helps pinpoint the exact source of the problem, opening the door to more accurate diagnosis and better-targeted treatments.

“This study not only challenges our existing understanding of HIT but also revolutionises how we think about the immune response overall,” said Ishac Nazy, senior author of the study and scientific director of the McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory and co-director of the Michael G. DeGroote Center for Transfusion Research (MCTR).

“This work corrects decades of misunderstanding in HIT. This status quo was a key reason behind the high rate of false-positive test results and frequent misdiagnoses in HIT, which can lead to severe consequences for patients, including unnecessary treatment or avoidable complications. Our findings lay the groundwork for more accurate diagnostics and targeted treatments,” said Nazy, a professor in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences at McMaster.

The research team was comprised of scientists from the McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory (MPIL) within MCTR as well as collaborators from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

They analysed blood samples from nine patients diagnosed with HIT. In each case, they found that the antibodies targeting platelet factor 4 (PF4) – a protein involved in blood clotting – were monoclonal. This suggests that HIT may be driven by a highly specific immune reaction, rather than a generalised one.

“This discovery could reshape how we diagnose HIT and eventually how we treat it,” said Jared Treverton, first author of the study and a PhD candidate at McMaster. “Knowing that HIT is caused by a monoclonal antibody will allow us to develop improved tests specific to patients with this disorder and design better targeted therapies. This is a major step towards making diagnostics more accurate and treatments much safer.”

The findings are expected to have immediate relevance for haematologists, laboratory specialists, and researchers in immunology, as well as for patients receiving heparin in hospitals across Canada and around the world.

Source: McMaster University