Fungal Microbiota May Explain Antibiotics’ Long Term Effects in Infants

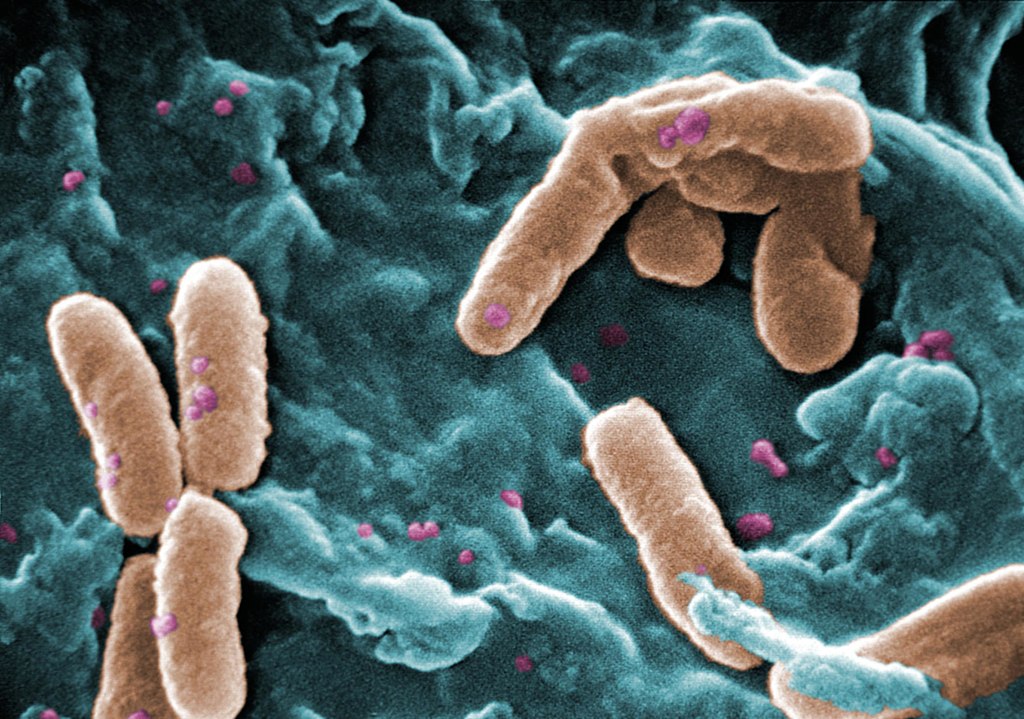

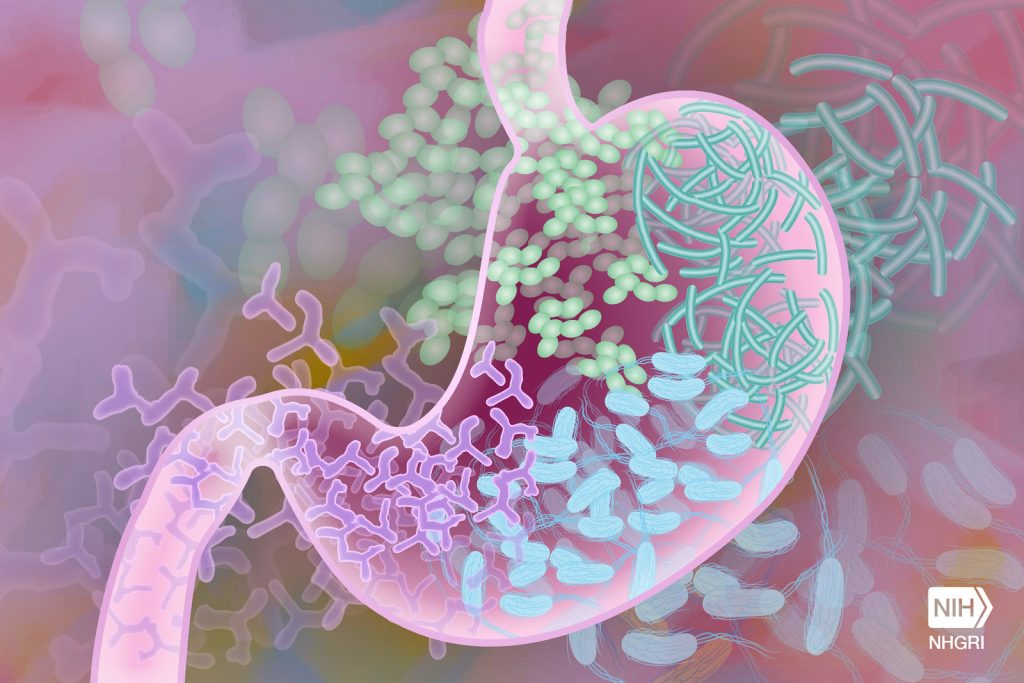

In infants treated with antibiotics, fungal gut microbiota are more abundant and diverse compared with the control group even six weeks following the start of the antibiotic course, according to a study published in the Journal of Fungi. The study’s authors suggest that reduced competition from gut bacteria being killed by antibiotics left more space for fungi to multiply.

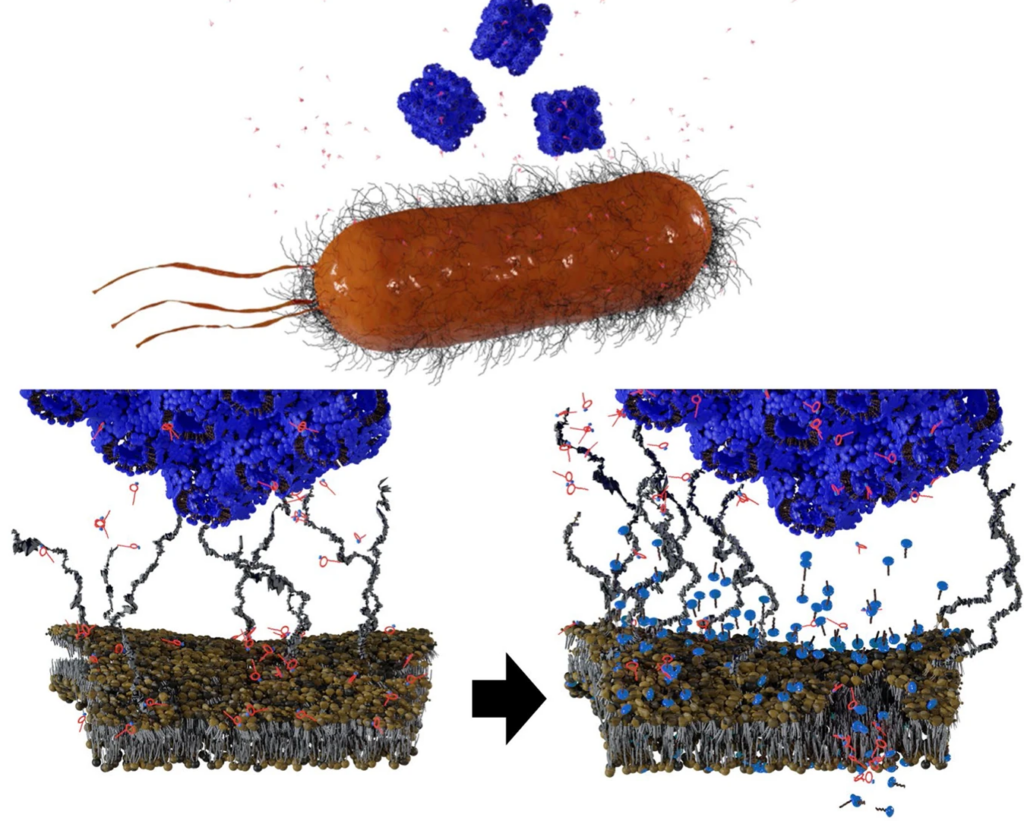

“The results of our research strongly indicate that bacteria in the gut regulate the fungal microbiota and keep it under control. When bacteria are disrupted by antibiotics, fungi, Candida in particular, have the chance to reproduce,” explained PhD student Rebecka Ventin-Holmberg from the University of Helsinki.

A new key finding in the study was that the changes in the fungal gut microbiota, together with the bacterial microbiota, may be partly responsible for the long-term adverse effects of antibiotics on human health.

Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed drugs for infants, causing changes in the gut microbiota at its most important developmental stage. These changes are more long-term compared to those in adults.

“Antibiotics can have adverse effects on both the bacterial and the fungal microbiota, which can result in, for example, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea,” Ventin-Holmberg said.

“In addition, antibiotics increase the risk of developing chronic inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and they have been found also to have a link to overweight,” she added.

These long-term effects are thought to be caused, at least in part, by an imbalance in the gut microbiota.

This study involved infants with a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection who had never previously received antibiotics. While some of the children were given antibiotics due to complications, others received no antibiotic therapy throughout the study.

“Investigating the effects of antibiotics is important for the development of techniques that can be used to avoid chronic inflammatory diseases and other disruptions to the gut microbiota in the future,” Ventin-Holmberg emphasised.

While there have been many studies on the effect of antibiotics on bacterial microbiota, there has been a lack of studies on fungal microbiota. This study’s findings indicate that fungal microbiota may also have a role in the long-term effects of imbalance in the gut microbiota.

“Consequently, future research should focus on all micro-organisms in the gut together to better understand their interconnections and to obtain a better overview of the microbiome as a whole,” Ventin-Holmberg noted.

Source: University of Helsinki