Study Shows that Intermittent Fasting Might Improve Alzheimer’s Symptoms

Circadian disruption is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, affecting nearly 80% of patients with issues such as difficulty sleeping and worsening cognitive function at night. Currently there are no treatments for Alzheimer’s that target this aspect of the disease.

A new study in Cell Metabolism from researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine has shown in mice that it is possible to correct the circadian disruptions seen in Alzheimer’s disease with time-restricted feeding, a type of intermittent fasting focused on limiting the daily eating window without limiting the amount of food consumed.

In the study, mice that were fed on a time-restricted schedule showed improvements in memory and reduced accumulation of amyloid proteins in the brain. The authors say the findings will likely result in a human clinical trial.

“For many years, we assumed that the circadian disruptions seen in people with Alzheimer’s are a result of neurodegeneration, but we’re now learning it may be the other way around – circadian disruption may be one of the main drivers of Alzheimer’s pathology,” said senior study author Paula Desplats, PhD, professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “This makes circadian disruptions a promising target for new Alzheimer’s treatments, and our findings provide the proof-of-concept for an easy and accessible way to correct these disruptions.”

People with Alzheimer’s experience a variety of disruptions to their circadian rhythms, including changes to their sleep/wake cycle, increased cognitive impairment and confusion in the evenings, and difficulty falling and staying asleep.

“Circadian disruptions in Alzheimer’s are the leading cause of nursing home placement,” said Desplats. “Anything we can do to help patients restore their circadian rhythm will make a huge difference in how we manage Alzheimer’s in the clinic and how caregivers help patients manage the disease at home.”

Boosting the circadian clock is an emerging approach to improving health outcomes, and one way to accomplish this is by controlling the daily cycle of feeding and fasting. The researchers tested this strategy in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, feeding the mice on a time-restricted schedule where they were only allowed to eat within a six-hour window each day. For humans, this would translate to about 14 hours of fasting each day.

Compared to control mice who were provided food at all hours, mice fed on the time-restricted schedule had better memory, were less hyperactive at night, followed a more regular sleep schedule and experienced fewer disruptions during sleep. The test mice also performed better on cognitive assessments than control mice, demonstrating that the time-restricted feeding schedule was able to help mitigate the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

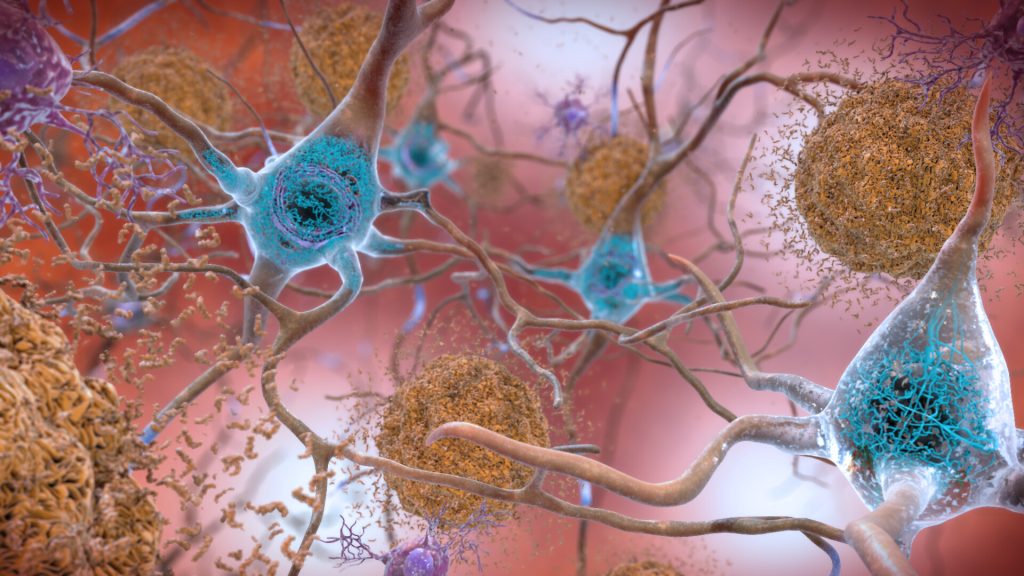

The researchers also observed improvements in the mice on a molecular level. In mice fed on a restricted schedule, the researchers found that multiple genes associated with Alzheimer’s and neuroinflammation were expressed differently. They also found that the feeding schedule helped reduce the amount of amyloid protein that accumulated in the brain. Amyloid deposits are one of the most well-known features of Alzheimer’s disease.

Because the time-restricted feeding schedule was able to substantially change the course of Alzheimer’s in the mice, the researchers are optimistic that the findings could be easily translatable to the clinic, especially since the new treatment approach relies on a lifestyle change rather than a drug.

“Time-restricted feeding is a strategy that people can easily and immediately integrate into their lives,” said Desplats. “If we can reproduce our results in humans, this approach could be a simple way to dramatically improve the lives of people living with Alzheimer’s and those who care for them.”