Why Some Patients Respond Poorly to Wet Macular Degeneration Treatment

A new study from researchers at Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine explains not only why some patients with wet age-related macular degeneration (or “wet” AMD) fail to have vision improvement with treatment, but also how an experimental drug could be used with existing wet AMD treatments to save vision.

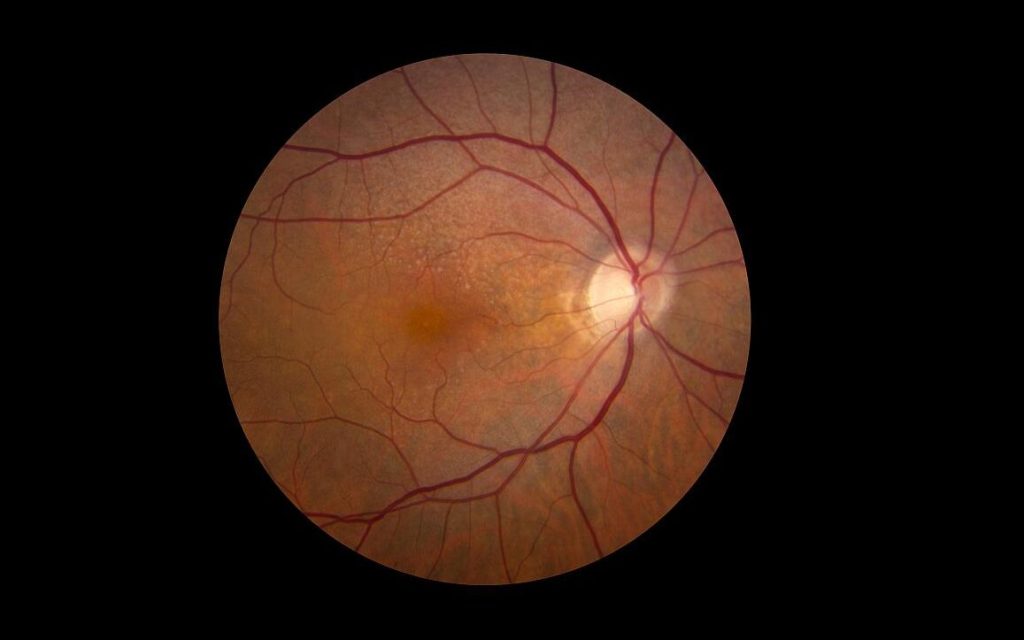

Wet AMD, one of two kinds of AMD, is a progressive eye condition caused by an overgrowth of blood vessels in the retina. Such blood vessels – caused by an overexpression of a protein known as VEGF that leads to blood vessel growth – then leak fluid or bleed and damage the retina, causing vision loss.

Despite the severe vision loss often experienced by people with wet AMD, less than half of patients treated with monthly eye injections, known as anti-VEGF therapies, show any major vision improvements. Additionally, for those who do benefit with improved vision, most will lose those gains over time.

Now, in the full report published November 4 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the Wilmer-led team of researchers share how such anti-VEGF therapies may actually contribute to lack of vision improvements by triggering the overexpression of a second protein. Known as ANGPTL4, the protein is similar to VEGF, as it can also stimulate overproduction of abnormal blood vessels in the retina.

“We have previously reported that ANGPTL4 was increased in patients who did not respond well to anti-VEGF treatment,” says Akrit Sodhi, MD, PhD, corresponding author and associate professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Wilmer Eye Institute. “What we saw in this paper was a paradoxical increase of ANGPTL4 in patients that received anti-VEGF injections – the anti-VEGF therapy itself turned on expression of this protein.”

The team compared VEGF and ANGPTL4 levels in the eye fluid of 52 patients with wet AMD at various stages of anti-VEGF treatment. Prior to anti-VEGF injections, patients with wet AMD had high levels of ANGPTL4 and VEGF proteins. After treatment, their VEGF levels predictably decreased, yet ANGPTL4 levels rose higher, indicating ANGPTL4 remained active following the anti-VEGF injections and the treatments contributed to an increase in ANGPTL4. Such ANGPTL4 activity can lead to blood vessel overgrowth and lack of vision improvement.

The team then investigated ways to bridge the gap between patients with increased ANGPTL4 following anti-VEGF treatments by testing the experimental drug 32-134D in mice with wet AMD. The drug decreases levels of a third protein, HIF-1, known to be involved in wet AMD and diabetic eye disease for its role in switching on VEGF production. Researchers believed the HIF-inhibitor 32-134D would have a similar effect on ANGPTL4 following anti-VEGF treatment, since ANGPTL4 production is also turned on by HIF-1.

In mice treated with 32-134D, the team observed a decrease in HIF-1 levels and VEGF, as well as decreased levels of ANGPTL4 and blood vessel overgrowth. Mice treated only with anti-VEGF therapies corroborated the team’s findings in human patients: levels of VEGF were lower, yet ANGPTL4 levels rose, preventing anti-VEGF therapies from fully working to prevent blood vessel growth (and vision loss). Researchers also determined that combining 32-134D with anti-VEGF treatments prevented the increase in HIF-1, VEGF and ANGPTL4. This treatment combination was more effective than either drug alone, showing promise for treating wet AMD.

“This work exposes a way to improve anti-VEGF therapy for all patients and potentially help a subset of patients with wet AMD who still lose vision over time despite treatment,” Sodhi says. “Our hope is that this [project] will further the three goals we have related to wet AMD: make current therapies as effective as possible, identify new therapies, and prevent people from ever getting wet AMD.”

Source: John Hopkins Medicine