Community-acquired Antimicrobial Resistant UTIs can be More Deadly

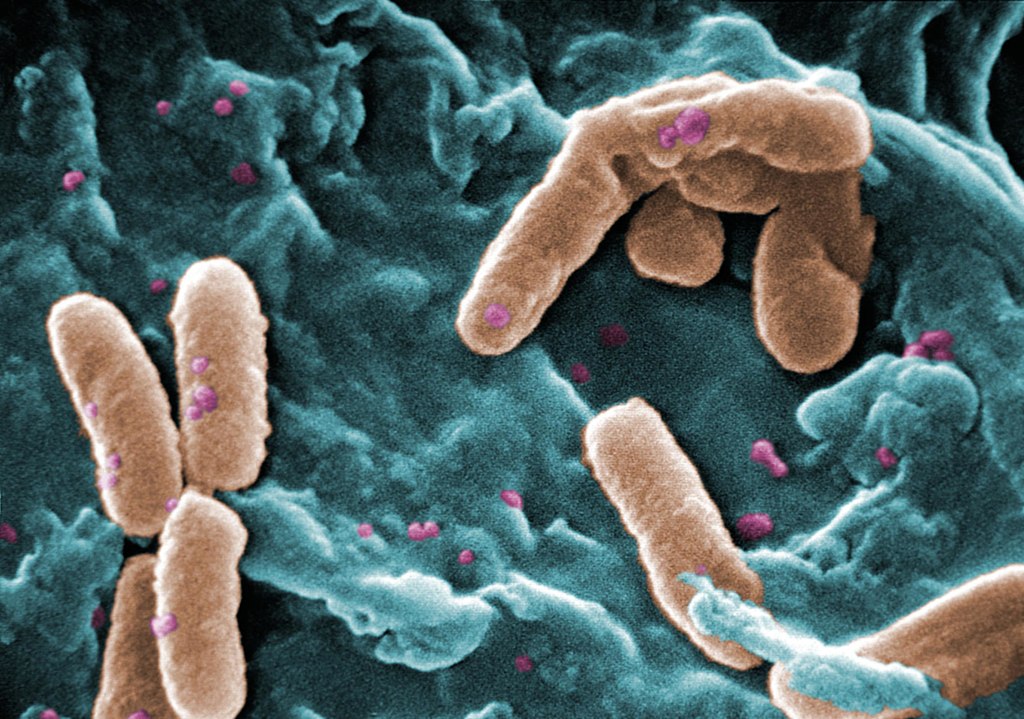

A study from Australia’s scientific organisation CSIRO has revealed that antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria in urinary tract infections are more lethal, especially Enterobacteriaceae. The findings are published online in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) bacteria can be passed between humans: through hospital transmission and community transmission. While hospital acquired resistance is well researched, there are few studies focusing on the burden of community transmission.

To address this, the study analysed data from 21 268 patients across 134 Queensland hospitals who acquired their infections in the community. The researchers found that patients were almost two and a half (2.43) times more likely to die from community acquired drug-resistant UTIs caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and more than three (3.28) times more likely to die from community acquired drug-resistant blood stream infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae than those with drug-sensitive infections. The high prevalence of UTIs make them a major contributor to antibiotic use, said CSIRO research scientist, Dr Teresa Wozniak.

“Our study found patients who contracted drug-resistant UTIs in the community were more than twice as likely to die from the infection in hospital than those without resistant bacteria,” Dr Wozniak said. “Without effective antibiotics, many standard medical procedures and life-saving surgeries will becoming increasingly life-threatening. “Tracking the burden of drug-resistant infections in the community is critical to understanding how far antimicrobial resistance is spreading and how best to mitigate it.”

The study’s findings will provide further guidance for managing AMR in the community, such as developing AMR stewardship programs that draw on data from the population being treated.

CEO of CSIRO’s Australian e-Health Research Centre, Dr David Hansen, said the magnitude of the AMR problem needs to be understood to mitigate it. “Tracking community resistance is difficult because it involves not just one pathogen or disease but multiple strains of bacteria,” Dr Hansen said. “Until now we haven’t been using the best data to support decision making in our fight against AMR. Data on community acquired resistance is an important contribution to solving the puzzle. “Digital health has an important role in using big data sets to describe patterns of disease and drive important population health outcomes.”

Source: CSIRO