Our HIV Response Will Collapse Without US Funding – Unless We Act Urgently

Reassurances that state clinics will pick up the lost services are empty

South Africa faces its worst health crisis in 20 years. Worse than COVID, and one that will overshadow diabetes as a major killer, while pouring petrol on a dwindling TB fire. But it is preventable if our government steps up urgently.

Nearly eight-million people have HIV in South Africa; they need life-long antiretroviral medicines to stay healthy.

The near-total removal of US government funding last week, a programme called PEPFAR, will see every important measure of the HIV programme worsen, including hospitalisations, new infections in adults and children, and death. Unless government meaningfully steps in to continue funding the network of highly efficient organisations that currently fill key gaps in national care, an epidemic that was tantalisingly close to coming under control will again be out of our reach. Millions of people in South Africa will become infected with HIV and hundreds of thousands more will die in the next ten years. 2025 will end much more like 2004, when we started our HIV treatment programme.

Many fail to recognize the danger. Commentators, public health officials, and government spokespeople have downplayed the US financial contributions to the HIV response, suggesting services can be absorbed within current services. The funding cuts amount to approximately 17% of the entire budget for HIV and largely go to salaries for health staff. On the face of it, this indeed seems replaceable. So why are the consequences so deadly?

To understand the impact, one must recognize how US funding has supported HIV care. The money is largely allocated to a network of non-government organisations through a competitive, focused, and rigorously monitored program in four key areas:

- Active case finding: The best way to prevent new cases of HIV is find everyone with the disease early on, and get them on treatment. These organisations deploy people in high-risk areas, to test for HIV and screen for TB, and shepherd people who test positive to treatment programmes. People are almost always healthy when they start treatment, and remain healthy, with greatly reduced time to transmit the virus, and much less chance of ever “burdening” the health sector with an opportunistic infection. They are hugely cost-effective.

- Tracing people who disappear from care: Patients on antiretrovirals fall out of care for many reasons, ranging from changing their address, to life chaos such as losing their job or mental illness. Or they are simply mixed up in the filing dysfunction within clinics. The US supported programmes helped finding people ‘lost from care’, maintaining systems able to track who has not come back, and how to contact them, often spending considerable time cleaning redundant records as people move between facilities.

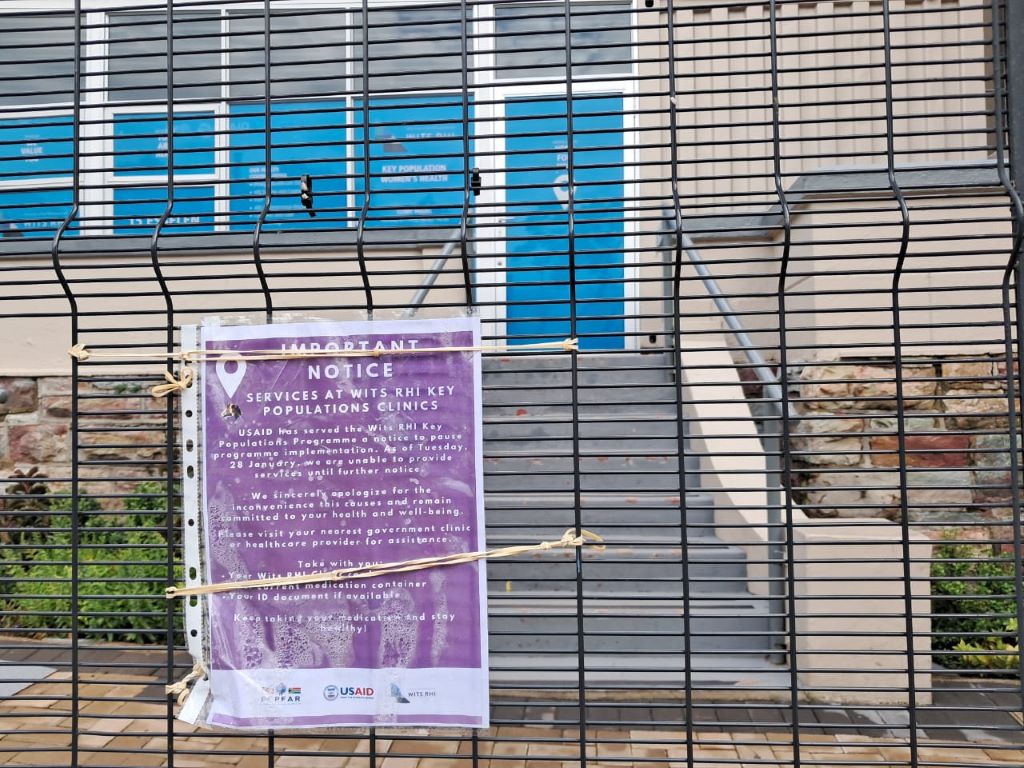

- Vulnerable population programmes: Services include those for sex workers, LGBTQ+ people, adolescents, people who use drugs, and victims of gender violence. These programs are for people who need tailored services beyond the straightforward HIV care offered in state clinics. They are often discriminated against in routine services and also at significant risk of contracting HIV.

- Supporting parts of the health system: This includes technical positions supporting medicine supply lines, laboratories and large information systems, as well as organisations doing advocacy or monitoring the quality of services. All of this keeps the health system ticking over.

In central Johannesburg, where I work, HIV testing services have collapsed. The people who fell out of programmes are not coming back. HIV prevention and TB screening have largely stopped.

Reassurances that state clinics will pick up testing are empty – the staff do not exist, and testing has not resumed. State clinics do not trace people who fall out of care for any illness, let alone for HIV. The data systems maintained by PEPFAR-supported organisations are now gone.

What happens now? The first hard sign that things are failing will be a large drop in the number of people starting treatment, versus what happened in the same month one year ago. The next metric to watch will be hospitalisations for tuberculosis and other infections associated with untreated HIV infection. This will happen towards the end of the year, as immune systems fail. Not long after, death rates will rise. We will see that in death certificates among younger people – the parents and younger adults.

Unfortunately, much of this information will not be available to the health department for at least a year or two, because among the staff laid off in this crisis are the data collectors for the programmes that tracked vital metrics.

The above should come as no surprise, especially to the public health commentators and health department, which is why it is so surprising to hear how certain they are that the PEPFAR programme can easily be absorbed into the state services. The timing of this crisis could not be worse, with huge budget holes in provincial health departments.

Why should this be a priority? After starting the HIV programme in 2004, we spent the next few years muddling through how to deliver antiretrovirals to millions of people in primary care, before we realised we also needed to diagnose them earlier. In 2004, the average CD4 count (a measure of immune strength) at initiation of treatment was about 80 cells/ul, devastatingly low – normal is > 500 cells/ul. A quarter were ill with TB.

This CD4 count average took years to go up, but only by pushing testing into clinic queues, communities, and special services for key populations, not waiting till they were sick. Recently, the average initiation CD4 count was about 400 cells/ul, stopping years of transmission, with most people healthy, and only a small number with TB.

There are many reasons to criticise the relationship between PEPFAR and the health department. It suited both parties to have a symbiotic relationship that meant each got on with their job and ticked their respective output boxes, but neither had to tussle with the messiness of trying to move the PEPFAR deliverables into the health department. As we move forward, learning from these fragilities to plan for the future of the HIV care programme, and for other diseases, will be critical.

Since the suspension of funding, many people have said, “We don’t hear much about HIV anymore”. That is because when the system works well, you don’t hear about it. Some things are far better compared to 2004:

- We have a government not in denial about HIV being a problem nor encouraging pseudoscience or crackpots.

- Our frontline health workers, in over 3000 clinics, have vast experience initiating and maintaining antiretrovirals.

- Antiretrovirals are cheaper, more potent, more durable, and safer.

- Treatment protocols are simpler.

- New infection rates are way down.

- Government delivery systems have improved.

- Data systems suggest that the majority of ‘lost’ patients are in care, often simply in another clinic.

A sensible emergency plan would do this:

- Fund existing programmes for a limited time, understanding that the level of reach and expertise is impossible for the health department to replicate at short notice.

- Couple this with a plan to make posts more sustainable over the next year or two.

- Learn from the PEPFAR programme that rigorously held organisations accountable, so that provinces can similarly be answerable for their HIV metrics.

- Ask hard questions why single patient identifiers, and government information systems, that could easily be linked to laboratory, pharmacy and radiology databases, are still not integrated within the public systems, as they are throughout the private health system.

- Accept that certain key functions and clinics may best be sited outside of the health department.

This will not save the large and valuable research programmes, which need other help. Much of the rest of Africa needs a Marshall Plan to rescue their entire HIV service, as they are almost totally dependent on US government funding.

But ideas like the above will preserve the current South African HIV response and allow us to imagine interventions that could end the disease as a threat for future generations.

No one disputes we need a move away from donor-assisted health programmes. But the scale and immense urgency of this oncoming emergency needs to be understood. We need a plan and a budget, and fast. Or we will have an overwhelmed hospital system and busy funeral services again.

Professor Francois Venter works for Ezintsha, a policy and research unit at Wits. He has been involved in the HIV programme since 2001, and ran several large PEPFAR programmes till 2012. Venter and his unit do not receive funding from PEPFAR, USAID or CDC. Thank you to several experts for supplying analysis and ideas for the initial draft of the article.

Published by GroundUp and Spotlight

Republished from GroundUp under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Read the original article.