By Now, Nearly All South Africans Have COVID Antibodies

The latest COVID seroprevalence survey shows that nearly every adult in South Africa has either been vaccinated or had COVID. For many, it’s both.

The study analysed blood from over 3000 blood donors. It was conducted by the South African National Blood Service, which is responsible for blood donations in eight provinces, and the Western Cape Blood Service.

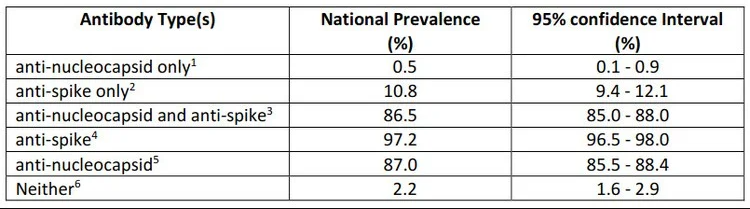

The researchers estimated that by March 2022, before the fifth wave which appears to have peaked in the last few weeks, 98% of adults had some detectable antibodies, whether from COVID or from vaccination. This means that only 2% had neither been vaccinated nor been infected.

Only 10% had been vaccinated but not infected by COVID.

(Note: The study has been published as a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed.)

What the survey tested for

Blood samples were collected and tested from 3395 consenting donors from all provinces in mid-March 2022. While blood donors are not precisely representative of the population, the researchers have argued that the study is representative enough.

This is the first time the blood services researchers have been able to look for two types of antibodies.

One test indicates if a sample has antibodies to the nucleocapsid proteins (anti-nucleocapsid antibodies). These antibodies develop if someone is infected, but won’t develop after a person receives a vaccine only (at least not those vaccines currently available in South Africa).

The other test indicates if the sample has antibodies to the spike protein (anti-spike antibodies). These antibodies develop when someone has been infected or has been vaccinated (or both).

Using these two tests together, researchers can, for the first time, evaluate the proportion of the population that has been vaccinated and not infected.

Results

After weighting the results to reflect national demographics, the researchers found that a mere 2% of the population had neither anti-spike nor anti-nucleocapsid antibodies. These are people who have likely never had COVID nor been vaccinated.

10% had only anti-spike antibodies. These are people who were likely vaccinated, but never infected.

The researchers noted that there is “an increasing incidence of reinfection” with the omicron wave.

Blood service survey is the best we have

The blood services have been regularly testing blood samples from donors throughout the pandemic, looking at the presence of anti-nucleocapsid antibodies.

While other surveys might be more representative of the population than the blood donor ones, these have been infrequently published or published long after the survey was conducted. By contrast the blood donor surveys are relatively affordable and quick to publish. Also, as far as we are aware, it is the only survey repeatedly testing the same group of people, so that comparisons across time are possible.

Past blood surveys

The blood services’ survey from samples taken in May 2021 estimated that 47% of the adult population had previously been infected.

The next survey of blood samples was taken in November 2021 after the delta wave. This was just before the omicron wave. The researchers estimated that about 70% of people had been infected.

The latest survey indicates that about 87% of people have been infected.

The previous surveys found that levels of infection differed by province. Now these differences have “largely disappeared as prevalence appears to have saturated”.

Differences across race

There are significant differences in rates of infection when different races are compared.

The November survey showed that about 80% of black donors and 40% of white donors had been infected with COVID.

In the latest survey the proportion of white and Asian donors that only have anti-spike antibodies (indicating vaccination but no infection) was higher than black and coloured donors.

The researchers suggest that “white donors are both unusually likely to avail themselves of vaccination, and they are unusually able to avoid exposure, for instance by working predominantly from home, [and] living in smaller family units.”

Article by By James Stent. Republished from GroundUp under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Source: GroundUp