Mastering a Third Robotic Arm is Surprisingly Quick

Busy doctors and nurses may have often found themselves wishing they had an extra arm to help with a patient or help with a difficult suture. Researchers around the world are developing supernumerary robotic arms to help workers achieve certain tasks unaided, or with less strain – but how long would it take to master learning an additional limb? The answer is: not long at all. One hour’s worth of training is enough for people to carry out a task with their ‘third arm’ as effectively as with a partner, according to the results of a new study published in IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology.

A new study by researchers at Queen Mary University of London, Imperial College London and The University of Melbourne has found that people can learn to use supernumerary robotic arms as effectively as working with a partner in just one hour of training.

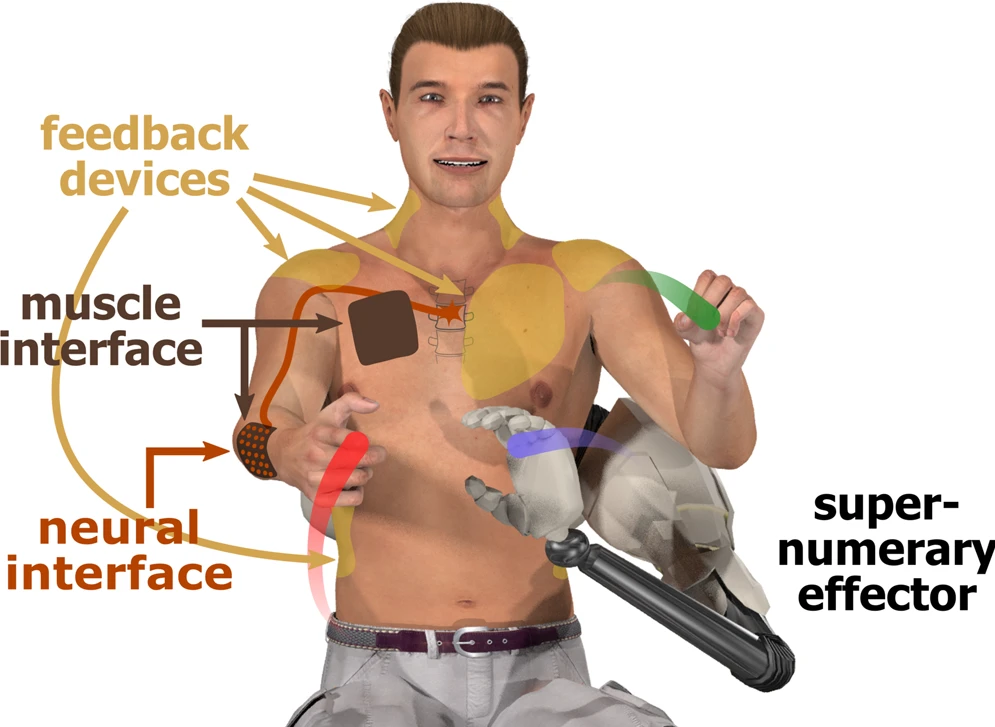

The study investigated the potential of supernumerary robotic arms to help people perform tasks that require more than two hands. The idea of human augmentation with additional artificial limbs has long been a staple of science fiction.

“Many tasks in daily life, such as opening a door while carrying a big package, require more than two hands,” said Dr Ekaterina Ivanova, lead author of the study from Queen Mary University of London. “Supernumerary robotic arms have been proposed as a way to allow people to do these tasks more easily, but until now, it was not clear how easy they would be to use.”

The study involved 24 participants who were asked to perform a variety of tasks with a supernumerary robotic arm. The participants were either given one hour of training in how to use the arm, or they were asked to work with a partner.

The results showed that the participants who had received training on the supernumerary arm performed the tasks just as well as the participants who were working with a partner. This suggests that supernumerary robotic arms can be a viable alternative to working with a partner, and that they can be learned to use effectively in a relatively short amount of time.

“Our findings are promising for the development of supernumerary robotic arms,” said Dr Ivanova. “They suggest that these arms could be used to help people with a variety of tasks, such as surgery, industrial work, or rehabilitation.”

Source: Queen Mary University of London