Fewer Types of Antibodies Produced with Age

Using short-lived killifish to study how the immune system weakens with ageing, scientists have found that fewer types of antibodies are produced as organisms age. Published in eLife, the findings could lead to ways to rejuvenate the immune systems of older people.

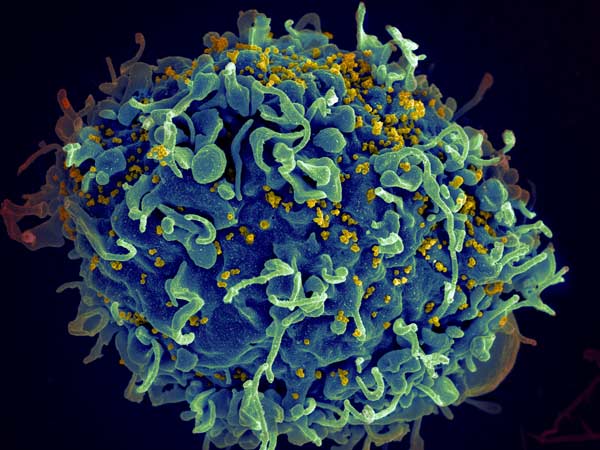

The immune system has to constantly respond to new attacks from pathogens and remember them in order to be protected during the next infection. For this purpose, B cells build a library of information that can produce a variety of antibodies to recognise the pathogens.

“We wanted to know about the antibody repertoire in old age,” explained lead researcher Dario Riccardo Valenzano. “It is difficult to study a human being’s immune system over his or her entire life, because humans live a very long time. Moreover, in humans you can only study the antibodies in peripheral blood, as it is problematic to get samples from other tissues. For this reason, we used the killifish. It is very short-lived and we can get probes from different tissues.”

The shortest-lived vertebrates that can be kept in the laboratory, killifishes quickly age over their three to four month lifespan and have become the focus of ageing research in recent years due to these characteristics.

The researchers were able to accurately characterise all the antibodies that killifish produce. They found that older killifish have different types of antibodies in their blood than younger fish. They also had a lower diversity of antibodies throughout their bodies.

The discovery could lead to ways to rejuvenate the immune system. “If we have fewer different antibodies as we age, this could lead to a reduced ability to respond to infections. We now want to further investigate why the B cells lose their ability to produce diverse antibodies and whether they can possibly be rejuvenated in the killifish and thus regain this ability,” Valenzano said.