What’s the Mechanism behind Behavioural Side Effects of GLP1RAs?

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP1RA) – medications for type 2 diabetes and obesity that have recently been making headlines due to a rise in popularity as weight loss agents – have been linked with behavioural side effects. A large population-based analysis in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism assessed whether certain genetic variants might help explain these effects.

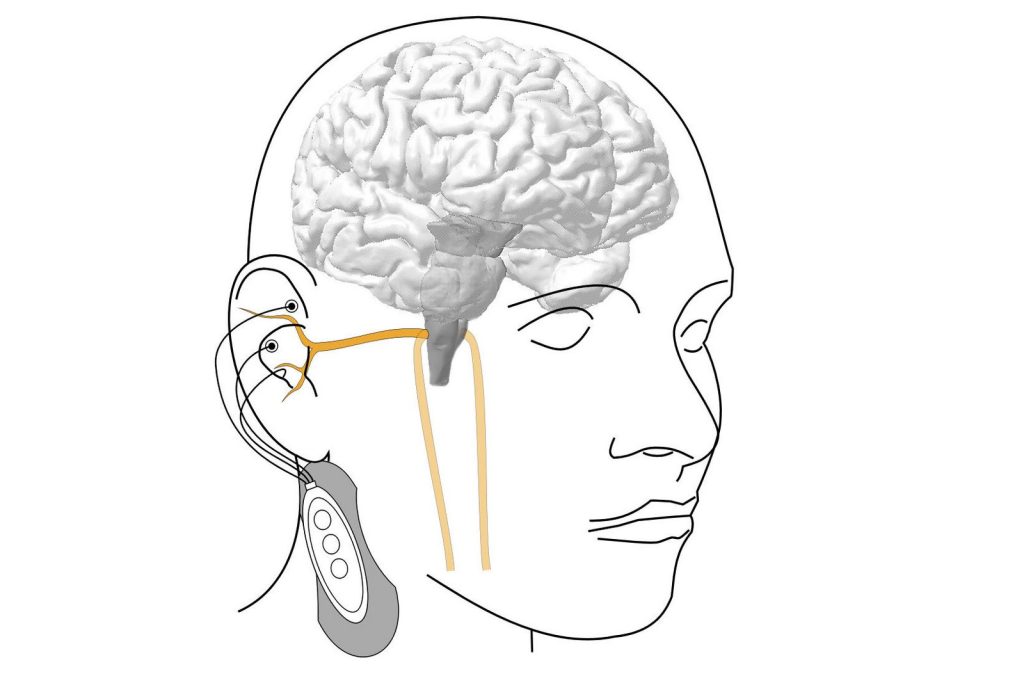

GLP1RA mimic the GLP-1 hormone in the body that helps control insulin and blood glucose levels and promotes feelings of satiety. GLP-1 binds to GLP1R on cells in the brain and pancreas.

Observational and epidemiological studies have shown that there may be neutral or protective effects of GLP1RAs on mental health symptoms. However, a study based on individuals taking GLP1RA suggests there is increased prescription of anti-depressants when used for treatment of diabetes. Early evidence in animal models suggest GLP1RA may decrease depressive and anxious symptoms, potentially presenting new treatment pathways; however, comparing these studies to human clinical evidence will not be possible for some time.

For the analysis, investigators examined common genetic variants in the GLP1R gene in 408 774 white British, 50 314 white European, 7 667 South Asian, 10 437 multiple ancestry, and 7641 African-Caribbean individuals.

Variants in the GLP1R gene had consistent associations with cardiometabolic traits (body mass index, blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes) across ancestries. GLP1R variants were also linked with risk-taking behavior, mood instability, chronic pain, and anxiety in most ancestries, but the results were less consistent. The genetic variants influencing cardiometabolic traits were separate from those influencing behavioral changes and separate from those influencing expression levels of the GLP1R gene.

The findings suggest that any observed behavioral changes with GLP1RA are likely not acting directly through GLP1R.

“Whilst it is not possible to directly compare genetic findings to the effects of a drug, our results suggest that behavioural changes are unlikely to be a direct result of the GLPRAs. Exactly how these indirect effects are occurring is currently unclear,” said corresponding author Rona J. Strawbridge, PhD, of the University of Glasgow, in the UK.

Source: Wiley