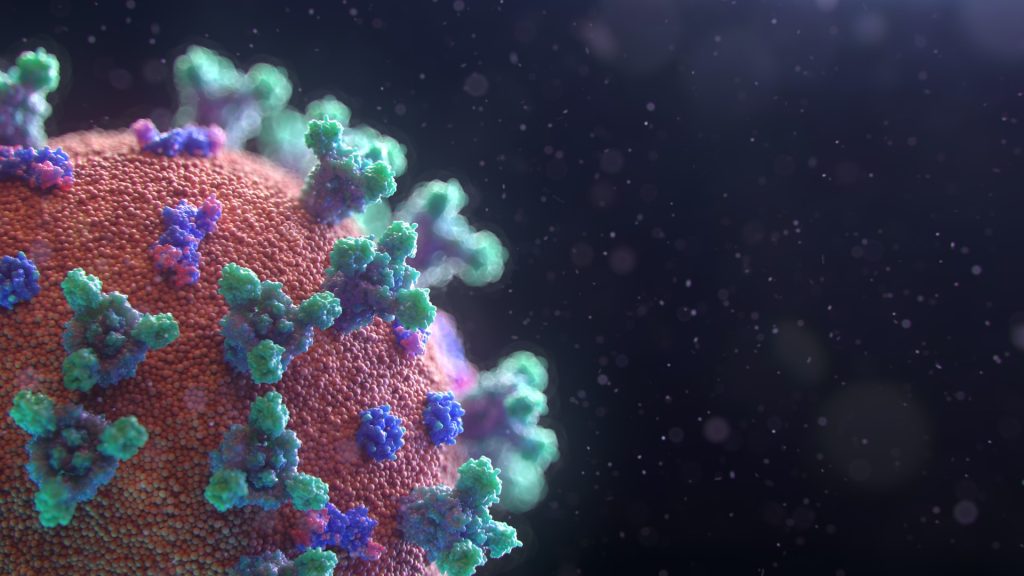

Elevated Body Temperature Helps Gut Microbiota to Fight Viruses

Researchers from The University of Tokyo have helped unravel the connection between high body temperature and increased viral resistance. Older adults are at a higher risk of contracting viral infections, research shows. Quite notably, they also have lower mean body temperatures – yet the effects of increased body temperature on fighting viral infections remain largely unexplored. The researchers found that higher temperature increased bile acids along with the infection-fighting capability of the gut microbiota. Their study was published in Nature Communications.

To conduct their experiments, the team used mice which were heat- or cold-exposed at 4°C, 22°C, or 36°C a week before influenza virus infection. After the viral infection was induced, the cold-exposed mice mostly died due to severe hypothermia, whereas the heat-exposed mice were highly resistant to the infection even at increasing doses of the virus. “High-heat-exposed mice raise their basal body temperature above 38°C, allowing them to produce more bile acids in a gut microbiota-dependent manner,” remarks Dr Takeshi Ichinohe from the Division of Viral Infection, The University of Tokyo, Japan.

The authors speculated that signalling of deoxycholic acid (DCA) from the gut microbiota and its plasma membrane-bound receptor “Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5” (TGR5) increased host resistance to influenza virus infection by suppressing virus replication and neutrophil-dependent tissue damage.

While working on these experiments, the team noticed that mice infected with the influenza virus showed decreased body temperatures nearly four days after the onset of the infection, and they snuggled together to stay warm!

The team noticed similar results after switching the influenza virus with SARS-CoV-2 and the study results were also validated using a Syrian hamster model. Their experiments revealed that body temperature over 38°C could increase host resistance to influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 infections. Moreover, they also found that such increase in body temperature catalyzed key gut microbial reactions, which in turn, led to the production of secondary bile acids. These acids can modulate immune responses and safeguard the host against viral infections.

Dr. Ichinohe explains, “The DCA and its nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist protect Syrian hamsters from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, certain bile acids are reduced in the plasma of COVID-19 patients who develop moderate I/II disease compared with the minor severity of illness group.”

The team then performed extensive analysis to gain insight into the precise mechanisms underlying the gut-metabolite-mediated host resistance to viral infections in heat-exposed rodents. Besides, they also established the role of secondary bile acids and bile acid receptors in mitigating viral infections.

“Our finding that reduction of certain bile acids in the plasma of patients with moderate I/II COVID-19 may provide insight into the variability in clinical disease manifestation in humans and enable approaches for mitigating COVID-19 outcomes,” concludes Dr. Ichinohe.

To briefly summarize, the published study reveals that the high-body-temperature-dependent activation of gut microbiota boosts the serum and intestinal levels of bile acids. This suppresses virus replication and inflammatory responses that follow influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infections.

A heartfelt appreciation to the Japanese researchers for placing their trust in their intuition and gut instincts!

Source: University of Tokyo