Infection by HIV Leaves a ‘Memory’ in Cells

Despite the benefits of antiretroviral therapy, people living with HIV often suffer from chronic inflammation, increasing the risk of developing comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and neurocognitive dysfunction. Now, a new study in Cell Reports explains why chronic inflammation may be happening and how suppression or even eradication of HIV in the body may not resolve it.

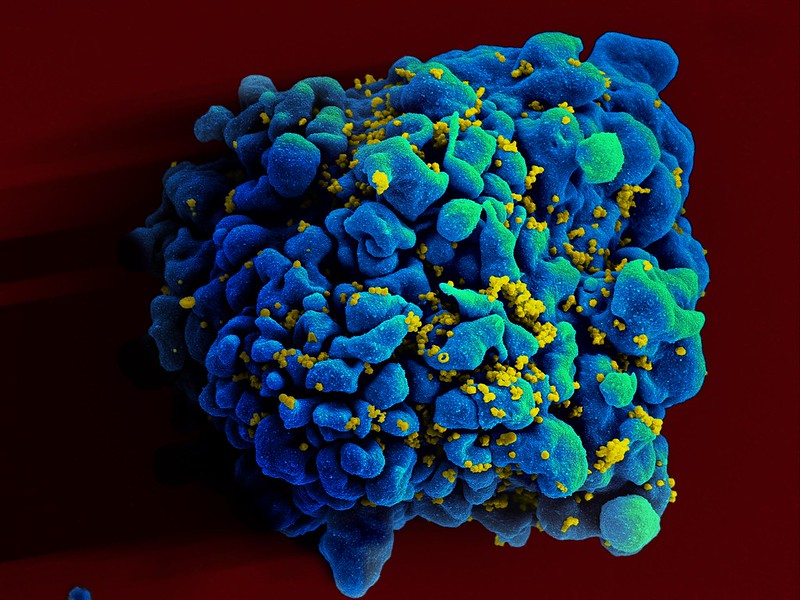

In the study, researchers from the George Washington University show how an HIV protein permanently alters immune cells in a way that causes them to overreact to other pathogens. When the protein is introduced to immune cells, genes in those cells associated with inflammation turn on, or become expressed, the study showed. These pro-inflammatory genes remain expressed, even when the HIV protein is no longer in the cells. According to the researchers, this “immunologic memory” of the original HIV infection is why people living with HIV are susceptible to prolonged inflammation, putting them at greater risk for developing cardiovascular disease and other comorbidities.

“This research highlights the importance of physicians and patients recognizing that suppressing or even eliminating HIV does not eliminate the risk of these dangerous comorbidities,” Michael Bukrinsky,professor of microbiology, immunology, and tropical medicine at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Science and lead author on the study, said. “Patients and their doctors should still discuss ways to reduce inflammation and researchers should continue pursuing potential therapeutic targets that can reduce inflammation and co-morbidities in HIV-infected patients.”

For the study, the research team isolated human immune cells in vitro and exposed them to the HIV protein Nef. The amount of Nef introduced to the cells is similar to the amount found in about half of HIV-infected people taking antiretrovirals whose HIV load is undetectable. After a period of time, the researchers introduced a bacterial toxin to generate an immune response from the Nef-exposed cells. Compared to cells that were not exposed to the HIV protein, the Nef-exposed cells produced an elevated level of inflammatory proteins, called cytokines. When the team compared the genes of the Nef-exposed cells with the genes of the cells not exposed to Nef, they identified pro-inflammatory genes that were in a ready-to-be-expressed status as a result of the Nef exposure.

According to Bukrinsky, the findings in this study could help explain why certain comorbidities persist following other viral infections, including COVID-19.

“We’ve seen this pro-inflammatory immunologic memory reported with other pathogenic agents and often referred to as ‘trained immunity,'” Bukrinsky explains. “While this ‘trained immunity’ evolved as a beneficial immune process to protect against new infections, in certain cases it may lead to pathological outcomes. The ultimate effect depends on the length of this memory, and extended memory may underlie long-lived inflammatory conditions like we see in HIV infection or long COVID.”

Source: George Washington University