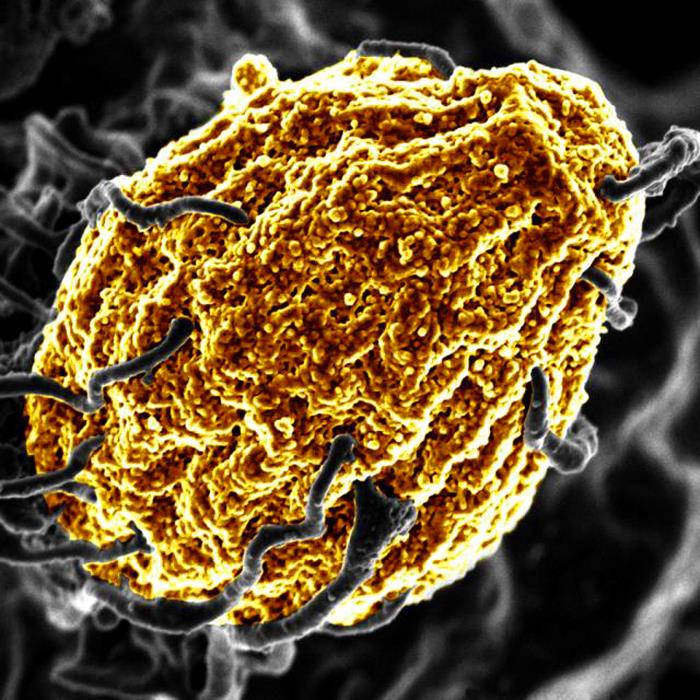

Monkeypox Symptoms Described in Case Series

A large case series on monkeypox was published in The New England Journal of Medicine, which will help direct the limited resources such as vaccines to contain the recent spread of the virus. In the study, clinicians led by Queen Mary University of London identified new clinical symptoms of monkeypox infection, which will aid future diagnosis and help to slow the spread of infection. This is the largest case study series to date, reporting on 528 confirmed monkeypox infections at 43 sites between 27 April and 24 June 2022.

Gay and bisexual men make up 98% of infected persons in the current spread of the virus. While in most cases sexual closeness is the most likely route of transmission, researchers stress that the virus can be transmitted by any close physical contact through large respiratory droplets and potentially through clothing and other surfaces.

There is a global shortage of both vaccines and treatments for human monkeypox infection. The findings of this study, including the identification of those most at risk of infection, will help to aid the global response to the virus. Public health interventions aimed at higher risk of exposure could help to detect and slow the spread of the virus. Recognising the disease, contact tracing and advising people to isolate will be key components of the public health response.

Many of the infected individuals reviewed in the study presented with symptoms not recognised in current medical definitions of monkeypox. These symptoms include single genital lesions and sores on the mouth or anus. The clinical symptoms are similar to those of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and can easily lead to misdiagnosis.

In some people, anal and oral symptoms have led to people being admitted to hospital for management of pain and difficulties swallowing. Since misdiagnosis can slow detection, hindering efforts to control the spread of the virus, this information is important for clinicians. This information will help increase diagnoses in persons from at-risk groups present with traditional STI symptoms.

Public health measures – such as enhanced testing and education – should be developed and implemented working with at-risk groups to ensure that they are appropriate, non-stigmatising, and to avoid messaging that could drive the outbreak underground.

Source: Queen Mary University of London