During Speech, The Corpus Callosum Hushes the Right Hemisphere

A study published in PLoS ONE has confirmed the role of the corpus callosum in language lateralisation, ie the distribution of language processing functions between the brain’s hemispheres. To get to this finding, the researchers applied advanced neuroimaging methods to study subjects performing an innovative language task for their study.

Functional asymmetry between the two cerebral hemispheres in performing higher-level cognitive functions is a major characteristic of the human brain. For example, the left hemisphere plays a leading role in language processing in most people. However, between 10% and 15% of people also use the right hemisphere to varying degrees for the same task.

Traditionally, language lateralisation to the right hemisphere was explained by handedness, as it is mainly found in left-handed and ambidextrous (using both hands equally well) individuals. But recent research has demonstrated a genetic difference in the way language is processed by left-handed and ambidextrous people. In addition to this, some right-handed people also involve their right hemisphere in language functions.

These findings prompted the scientists to consider alternative explanations, especially by looking at brain anatomy to find out why language functions can shift to the right hemisphere. Researchers at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain hypothesised that language lateralisation may have something to do with the anatomy of the corpus callosum, the largest commissural tract in the human brain connecting the two cerebral hemispheres.

The researchers asked 50 study participants to perform a sentence completion task. The subjects were instructed to read aloud a visually presented Russian sentence and to complete it with an appropriate final word (eg ‘Teper’ ministr podpisyvaet vazhnoe…‘ – ‘Now the minister is signing an important …’). At the same time, the participants’ brain activity was recorded using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Additionally, the volume of the corpus callosum was measured in each subject.

A comparison between the fMRI data and the corpus callosum measurements revealed that the larger the latter’s volume, the less lateralisation of the language function to the right hemisphere was observed.

When processing language, the brain tends to use the left hemisphere’s resources efficiently and the corpus callosum suppresses any additional involvement of the right hemisphere. The larger a person’s corpus callosum, the less involved their right hemisphere is in language processing (and vice versa). This finding is consistent with the inhibitory model suggesting that the corpus callosum inhibits the action of one hemisphere while the other is engaged in cognitive tasks.

The study’s innovative design and use of advanced neuroimaging have made this conclusion possible. Brain lateralisation in language processing is usually hard to measure accurately, as typical speech tasks used in earlier studies (eg image naming, selecting words that begin with a certain letter or listening to speech) tend to cause activation only in some parts of the brain responsible for language functions but not in others. Instead, we developed a unique speech task for fMRI: sentence completion, which reliably activates all language areas of the brain.

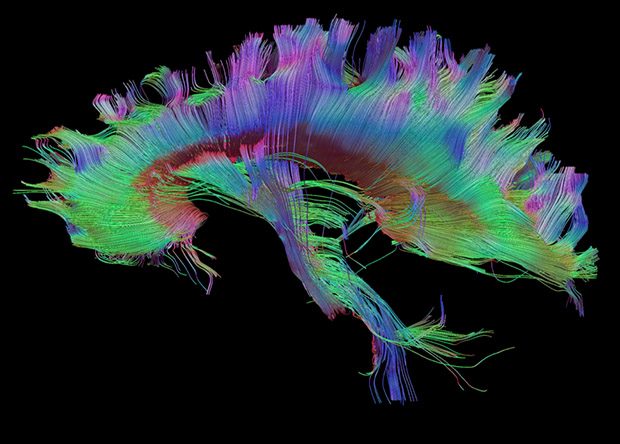

The researchers reconstructed the volume and properties of the corpus callosum from MRI data using an advanced tractography technique: constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD). This is more suitable than traditional diffusion tensor imaging for modelling crossing fibres in the smallest unit of volume, the voxel (3D pixel), and is therefore more reliable.

Source: National Research University Higher School of Economics