Newly Discovered Bone Stem Cell Drives Premature Skull Fusion

Craniosynostosis, the premature fusion of the top of the skull in infants, is caused by an abnormal excess of a previously unknown type of bone-forming stem cell, according to a preclinical study published in Nature.

Occurring in one in 2500 babies, craniosynostosis arises from one of several possible gene mutations. By constricting brain growth, it can lead to abnormal brain development if not corrected surgically. In complex cases, multiple surgeries are needed.

Led by researchers at and led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, the team focused on what happens in the skull of mice with one of the most common mutations found in human craniosynostosis. They found that the mutation drives premature skull fusion by inducing the abnormal proliferation of a type of bone-making stem cell, the DDR2+ stem cell, that had never been described before.

“We can now start to think about treating craniosynostosis not just with surgery but also by blocking this abnormal stem cell activity,” said study co-senior author Dr Matt Greenblatt, an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a pathologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

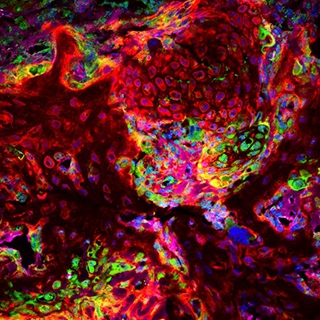

A new stem cell driving disorders of premature skull fusion was transplanted (red), showing that it makes the cartilage seen at sites of skull fusion (green). Credit: Greenblatt lab.

In a study published in Nature in 2018, Dr Greenblatt, study co-senior author Dr Shawon Debnath and their colleagues, described the discovery of a type of bone-forming stem cell they called the CTSK+ stem cell. Because this type of cell is present in the top of the skull, or “calvarium,” in mice, they suspected that it has a role in causing craniosynostosis.

For the new study, they knocked out genes associated with craniosynostosis in CSTK+ stem cells in mice. They expected that the gene deletion somehow would induce these calvarial stem cells to go into bone-making overdrive. This new bone would fuse the flexible, fibrous material called sutures in the skull that normally allow it to expand in infants.

“We were surprised to find that, instead of the mutation in CTSK+ stem cells leading to these stem cells being activated to fuse the bony plates in the skull as we expected, mutations in the CTSK+ stem cells instead led to the depletion of these stem cells at the sutures – and the greater the depletion, the more complete the fusion of the sutures,” Dr Debnath said.

The unexpected finding led the team to hypothesise that another type of bone-forming stem cell was driving the abnormal suture fusion. After further experiments, and a detailed analysis of the cells present at fusing sutures, they identified the culprit: the DDR2+ stem cell, whose daughter cells make bone using a different process than that utilised by CTSK+ cells.

The team found that CTSK+ stem cells normally suppress the production of the DDR2+ stem cells. But the craniosynostosis gene mutation causes the CTSK+ stem cells to die off, allowing the DDR2+ cells to proliferate abnormally.

Collaborating with other researchers, they found the human versions of DDR2+ stem cells and CTSK+ stem cells in calvarial samples from craniosynostosis surgeries—underscoring the likely clinical relevance of their findings in mice.

The findings suggest that inappropriate DDR2+ stem cell proliferation in the calvarium, in infants with craniosynostosis-linked gene mutations, could be treated by suppressing this stem cell population, through mimicking the methods that CTSK+ stem cells normally use to prevent expansion of DDR2+stem cells. The researchers found that the CTSK+ stem cells achieve this suppression by secreting a growth factor protein called IGF-1, and possibly other regulatory proteins.

“We observed that we could partly prevent calvarial fusion by injecting IGF-1 over the calvarium,” said study first author Dr Seoyeon Bok, a postdoctoral researcher in the Greenblatt laboratory.

“I can imagine DDR2+ stem cell-suppressing drug treatments being used along with surgical management, essentially to limit the number of surgeries needed or enhance outcomes,” Dr. Greenblatt said.

In addition to treatment-oriented research, he and his colleagues now are looking for other bone-forming stem cell populations in the skull.

“This work has uncovered much more complexity in the skull than we ever imagined, and we suspect the complexity doesn’t end with these two stem cell types,” Dr Greenblatt said.

Source: Weill Cornell Medicine