Monkeypox Virus can Linger for up to a Month on Surfaces

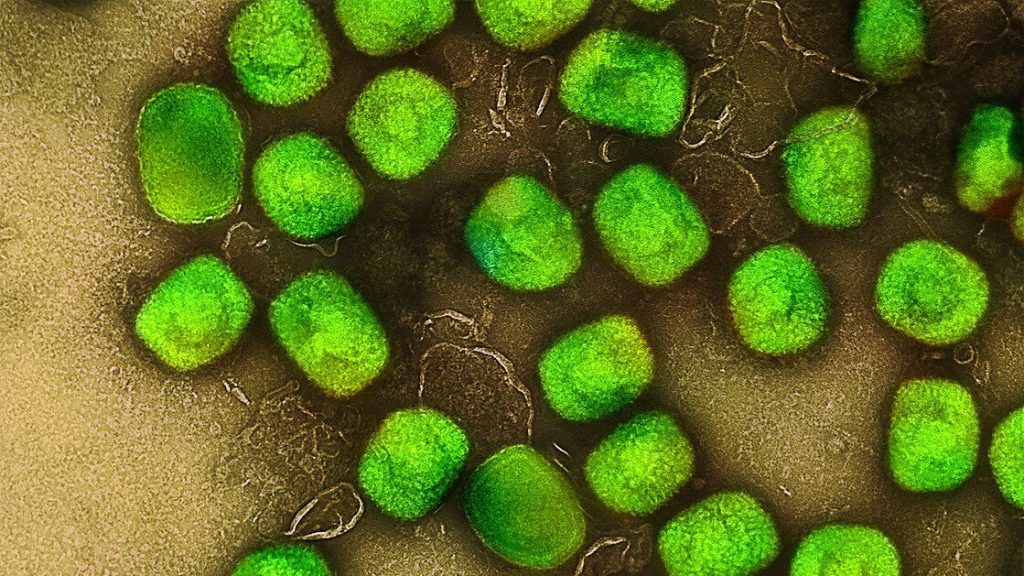

According to a study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the monkeypox virus remains infectious on steel surfaces for up to 30 days, especially in cold conditions, but can be effectively inactivated by alcohol-based disinfectants.

Smallpox viruses are notorious for their ability to remain infectious in the environment for a very long time. A study conducted by the Department of Molecular and Medical Virology at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, has shown that temperature is a major factor in this process: at room temperature, a monkeypox virus that is capable of replicating can survive on a stainless steel surface for up to 11 days, and at 4°C for up to a month. Consequently, it’s very important to disinfect surfaces. According to the study, alcohol-based disinfectants are very effective against monkeypox viruses, whereas hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants have proved inadequate.

Weeks of monitoring

Since 2022, the monkeypox virus has been transmitted more and more frequently from one human host to another. Although infections primarily result from direct physical contact, it’s also possible to contract the virus through contaminated surfaces, for example in the household or in hospital rooms. “Smallpox viruses are notorious for their ability to remain infectious in the environment for a very long time,” explains Dr Toni Meister from the Department for Molecular and Medical Virology at Ruhr University Bochum. “For monkeypox, however, we didn’t know the exact time frames until now.”

The researchers therefore studied them by applying the virus to sanitised stainless steel plates and storing them at different temperatures: at 4°C, at 22°C, which roughly corresponds to room temperature, and at 37°C. They determined the amount of infectious virus after different periods of time, ranging from 15 minutes to several days to weeks.

Viruses remain infectious for a long time

Regardless of the temperature, there was little change in the amount of infectious virus during the first few days. At 22 and 37°C, the virus concentration dropped significantly only after five days. At 37°C, no virus capable of reproducing was detected after six to seven days, at 22°C it took 10–11 days until infection was no longer possible. At 4°C, the amount of virus only dropped sharply after 20 days, and after 30 days there was no longer any danger of infection. “This is consistent with our experience that people can still contract monkeypox from surfaces in the household after almost two weeks,” points out Professor Eike Steinmann, Head of the Department for Molecular and Medical Virology.

In order to reduce the risk of infection in the event of an outbreak, it is therefore extremely important to disinfect surfaces. This is why the researchers tested the effectiveness of five common disinfectants. They found that alcohol-based or aldehyde-based disinfectants reliably reduced the risk of infection. A hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectant, however, didn’t inactivate the virus effectively enough in the study. “Our results support the WHO’s recommendation to use alcohol-based surface disinfectants,” concludes Toni Meister.

Source: Ruhr-University Bochum