Researchers Achieve Decolonisation of S. Aureus by Using Probiotics

A clinic trial published in The Lancet Microbe found that a promising approach to that ‘decolonised’ Staphylococcus aureus by using a probiotic instead of antibiotics. The probiotic Bacillus subtilis markedly reduced S. aureus colonisation in trial participants without harming the gut microbiota.

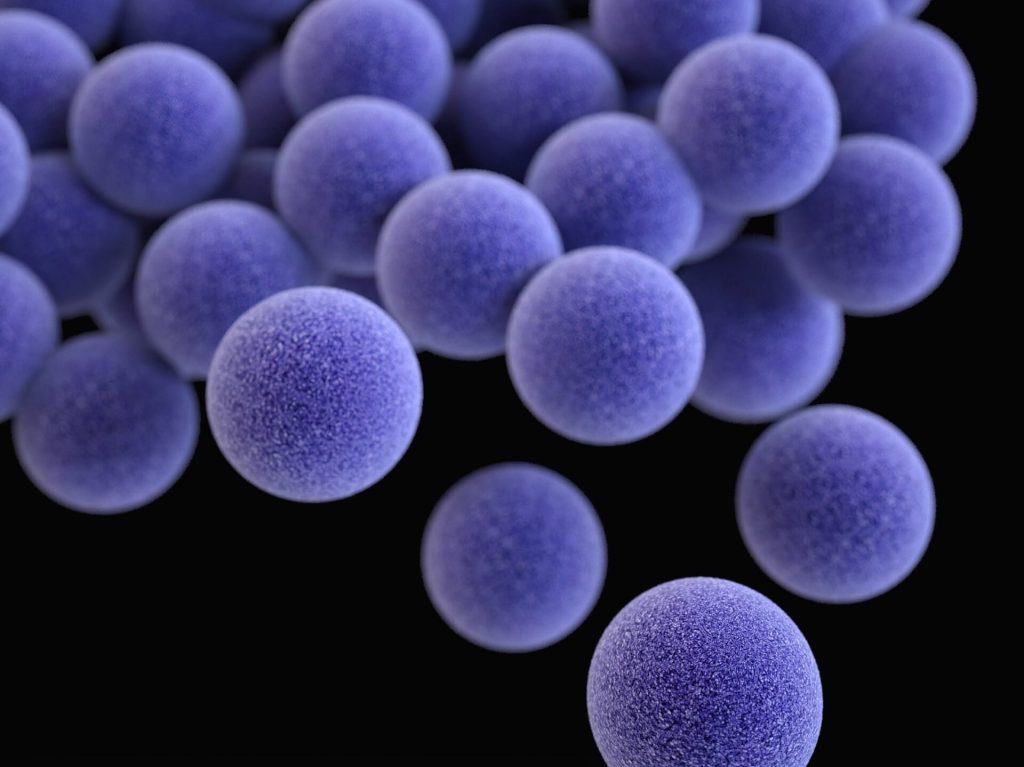

Staphylococcus aureus are colonising bacteria that often live in the nose, on the body and in the gut but if the skin barrier is broken or the immune system weakened, they can cause serious disease.

Preventing S. aureus infections by “decolonising” the body has gained increased attention as antibiotic resistance has spread, but large amounts of antibiotics are needed, damaging other microbiota and promoting more antibiotic resistance. So far, it appears that only nasal S. aureus colonisation can be targeted with topical antibiotics without doing too much harm, but bacteria quickly can recolonise in the nose from the gut.

Probiotics may be a way to complement or replace antibiotics, of which Bacillus is especially promising because it is administered orally as spores that can survive passage through the stomach and then temporarily grow in the intestine. In prior studies, Dr Otto’s group discovered an S. aureus sensing system needed for S. aureus to grow in the gut. They also found that fengycins, Bacillus lipopeptides that are part peptide and part lipid, stop the S. aureus sensing system from functioning, eliminating the bacteria.

In the clinical trial, conducted in Thailand, the research team tested whether this approach works in people. They enrolled 115 healthy participants, all of whom were colonised naturally with S. aureus. A group of 55 people received B. subtilis probiotic once daily for four weeks; a control group of 60 people received a placebo. After four weeks researchers evaluated the participants’ S. aureus levels in the gut and nose. They found no changes in the control group, but in the probiotic group they observed a 96.8% S. aureus reduction in the stool and a 65.4% reduction in the nose.

“The probiotic we use does not ‘kill’ S. aureus, but it specifically and strongly diminishes its capacity to colonise,” Dr. Otto said. “We think we can target the ‘bad’ S. aureus while leaving the composition of the microbiota intact.”

The researchers also found that levels of S. aureus bacteria in the gut far exceeded S. aureus in the nose, which for decades has been the focus of staph infection prevention research. This finding adds to the potential importance of S. aureus reduction in the gut.

“Intestinal S. aureus colonisation has been evident for decades, but mostly neglected by researchers because it was not a viable target for antibiotics,” Dr Otto said. “Our results suggest a way to safely and effectively reduce the total number of colonising S. aureus and also call for a categorical rethinking of what we learned in textbooks about S. aureus colonisation of the human body.”

The researchers plan to continue their work by testing the probiotic in a larger and longer trial. They note that their approach probably does not work as quickly as antibiotics, but can be used for long periods because the probiotic as used in the clinical trial does not cause harm.

Source: NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases