Drug Enhances Radiotherapy for Lung Cancer Metastases in the Brain

In new research, a team led by University of Cincinnati researchers has identified a potential new way to make radiation more effective and improve outcomes for patients with lung cancer that has spread to the brain. The study, led by first author Debanjan Bhattacharya, PhD, appears in the journal Cancers, and uses a benzodiazepine analogue.

According to the American Cancer Society, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, accounting for about one in five cancer deaths. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most prevalent type of lung cancer, making up approximately 80% to 85% of all lung cancer cases.

Up to 40% of lung cancer patients develop brain metastases during the course of the disease, and these patients on average survive between eight and 10 months following diagnosis.

Current standard of care treatments for lung cancer that spreads to the brain include surgical removal and stereotactic brain radiosurgery (using precisely focused radiation beams to treat tumours) as well as whole brain irradiation in patients with more than 10 metastatic brain lesions.

“Lung cancer brain metastasis is usually incurable, and whole brain radiation treatment is palliative, as radiation limits therapy due to toxicity,” said Bhattacharya, research instructor in the Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation Medicine in UC’s College of Medicine. “Managing potential side effects and overcoming resistance to radiation are major challenges when treating brain metastases from lung cancer. This highlights the importance of new treatments which are less toxic and can improve the efficacy of radiation therapy, are less expensive, and can improve the quality of life in patients.”

Research focus

Bhattacharya and his colleagues at UC focused on AM-101, a synthetic analogue, meaning it has a close resemblance to the original compound, in the class of benzodiazepine drugs. It was first developed by James Cook, a medicinal chemist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Prior to this study, AM-101’s effect in non-small cell lung cancer was unknown.

AM-101 is a particularly useful drug in the context of brain metastases in NSCLC, Bhattacharya said, as benzodiazepines are known to be able to pass through the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from potential harmful invaders that can also block some drugs from reaching their target in the brain.

Research results

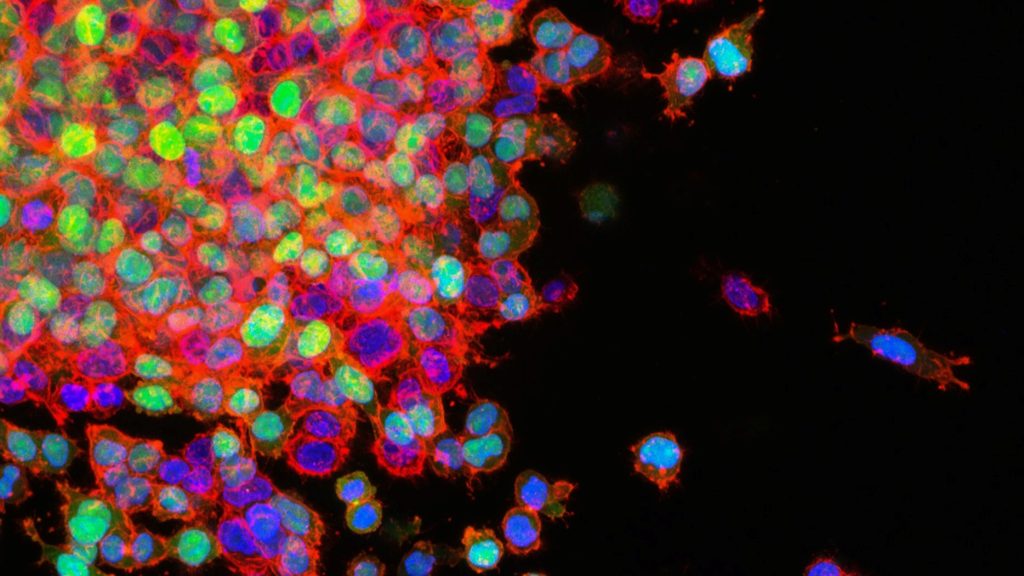

The team found that AM-101 activated GABA(A) receptors located in the NSCLC cells and lung cancer brain metastatic cells. This activation triggers the “self-eating” process of autophagy where the cell recycles and degrades unwanted cellular parts.

Specifically, the study showed that activating GABA(A) receptors increases the expression and clustering of GABARAP and Nix (an autophagy receptor), which boosts the autophagy process in lung cancer cells. This enhanced “self-eating” process of autophagy makes lung cancer cells more sensitive to radiation treatment.

Using animal models of lung cancer brain metastases, the team found AM-101 makes radiation treatment more effective and significantly improves survival. Additionally, the drug was found to slow down the growth of the primary NSCLC cells and brain metastases.

In addition to making radiation more effective, adding AM-101 to radiation treatments could allow for lower radiation doses, which could reduce side effects and toxicity for patients, Bhattacharya said. The team is now working toward opening Phase 1 clinical trials testing the combination of AM-101 and radiation both in lung cancer within the lungs and lung cancer that has spread to the brain.

Source: Aalto University