A Crystal Clear Look at Rabies Opens up New Vaccines

In a new study, researchers from La Jolla Institute have unveiled one of the first high-resolution looks at the rabies virus glycoprotein in its vulnerable ‘trimeric’ form. These new images, published in Science Advances, may open up a new vaccine for the deadly virus.

The CDC estimates that 59 000 people die from rabies virus every year, with 40% of those bitten by rabid animals being under 15. Some victims, especially kids, don’t realise they’ve been exposed until it is too late. The intense rabies treatment regimen is not widely available and the average $3800 is out of the reach of less well-off families.

Rabies vaccines, rather than treatments, are much more affordable and easier to administer. But according to Professor Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, of the La Jolla Institute, lead researcher of the new study, those vaccines also come with a massive downside.

“Rabies vaccines don’t provide lifelong protection. You have to get your pets boosted every year to three years,” she said. “Right now, rabies vaccines for humans and domestic animals are made from killed virus. But this inactivation process can cause the molecules to become misshapen – so these vaccines aren’t showing the right form to the immune system. If we made a better shaped, better structured vaccine, would immunity last longer?”

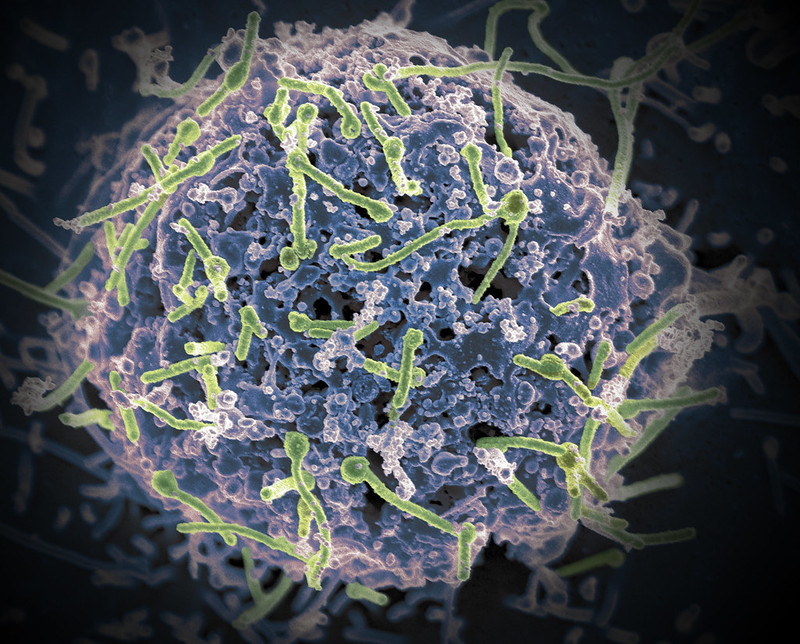

“The rabies glycoprotein is the only protein that rabies expresses on its surface, which means it is going to be the major target of neutralising antibodies during an infection,” said LJI Postdoctoral Fellow Heather Callaway, PhD, the study’s first author.

“Rabies is the most lethal virus we know. It is so much a part of our history – we’ve lived with its spectre for hundreds of years,” added Prof Saphire. “Yet scientists have never observed the organisation of its surface molecule. It is important to understand that structure to make more effective vaccines and treatments – and to understand how rabies and other viruses like it enter cells.”

Shapeshifting Rabies virus evades antibodies

Why rabies vaccines don’t provide long-term protection is still unclear, but they do know that its shape-shifting proteins are a problem.

The rabies glycoprotein has sequences that unfold and flip upward when needed, like a Swiss Army knife. The glycoprotein can shift back and forth between pre-fusion (before fusing with a host cell) and post-fusion forms. It can also come apart, changing from a trimer structure (where three copies come together in a bundle) to a monomer (one copy by itself).

This shapeshifting can make rabies invisible to human antibodies, which are built to recognise a single site on a protein. They cannot follow along when a protein transforms to hide or move those sites.

The new study gives scientists a critical picture of the correct glycoprotein form to target for antibody protection.

Capturing the glycoprotein at last

Over the course of three years, Callaway worked to stabilise and freeze the rabies glycoprotein in its pre-fusion form.

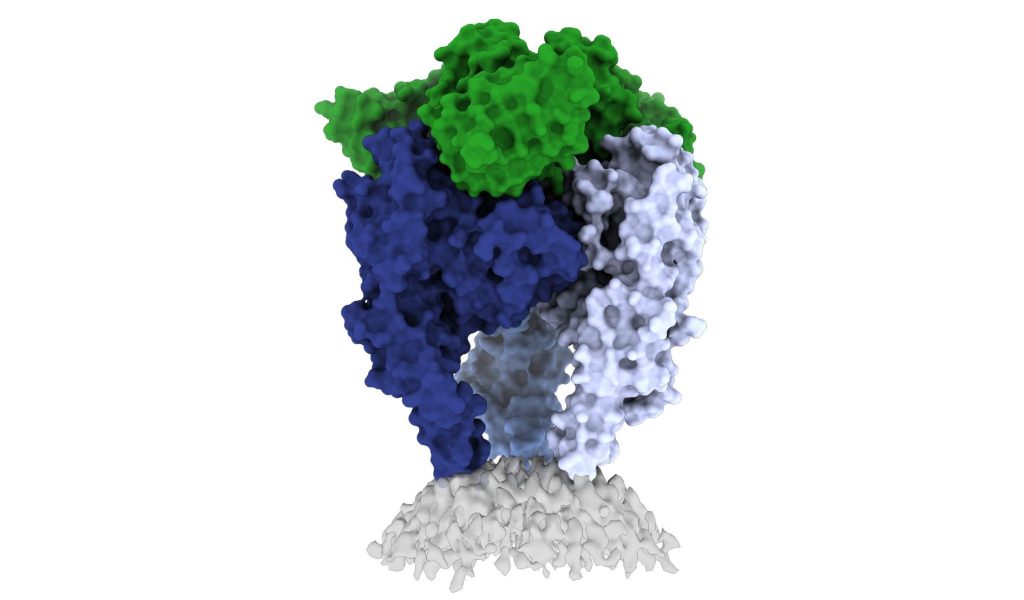

Callaway paired the glycoprotein with a human antibody, which helped her pinpoint one site where the viral structure is vulnerable to antibody attacks. The researchers then captured a 3D image of the glycoprotein using cutting-edge cryo-electron microscope equipment at LJI.

The new 3D structure highlights several key features researchers hadn’t seen before. Importantly, the structure shows the fusion peptides, the way they appear in real life. These two important sequences link the bottom of the glycoprotein to the viral membrane, but project into the target cell during infection. Getting stable image of these sequences is challenging: other rabies researchers have had to cut them off to try to get images of the glycoprotein.

Dr Callaway solved this problem by capturing the rabies glycoprotein in detergent molecules. “That let us see how the fusion sequences are attached before they snap upward during infection,” said Prof Saphire.

Now that scientists have a clear view of this viral structure, they can better design vaccines to create antibodies with a better picture of the targt.

“Instead of being exposed to four-plus different protein shapes, your immune system should really just see one – the right one,” said Dr Callaway. “This could lead to a better vaccine.”

Preventing a family of viruses

More images are needed of rabies virus and its relatives together with neutralising antibodies, and could reveal common antibody targets for lyssaviruses, which can also infect humans and animals. According to Dr Callaway, scientists are working on solving several of these structures, which could reveal antibody targets that lyssaviruses have in common.

“Because we didn’t have these structures of the rabies virus in this conformational state before, it’s been hard to design a broad-spectrum vaccine,” Dr Callaway said.