Antipsychotic Drugs Work Differently than Previously Believed, Study Finds

Antipsychotic drugs, used to treat schizophrenia, have many unpleasant side effects and are also ineffective for many patients, so new drugs are needed. New research published in Nature Neuroscience has discovered that antipsychotic drugs, which inhibit the overactive dopamine causing the symptoms of schizophrenia, interact with a completely different neuron than originally believed.

This new finding from Northwestern Medicine scientists provides a new avenue to develop more effective drugs to treat the debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia. Traditionally, researchers have screened antipsychotic drug candidates by evaluating their effects on mouse behaviour, but the approach used by a Northwestern lab outperformed these traditional approaches in terms of predicting efficacy in patients.

“This is a landmark finding that completely revises our understanding of the neural basis for psychosis and charts a new path for developing new treatments for it,” said lead investigator Jones Parker, assistant professor of neuroscience at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “It opens new options to develop drugs that have fewer adverse side effects than the current ones.”

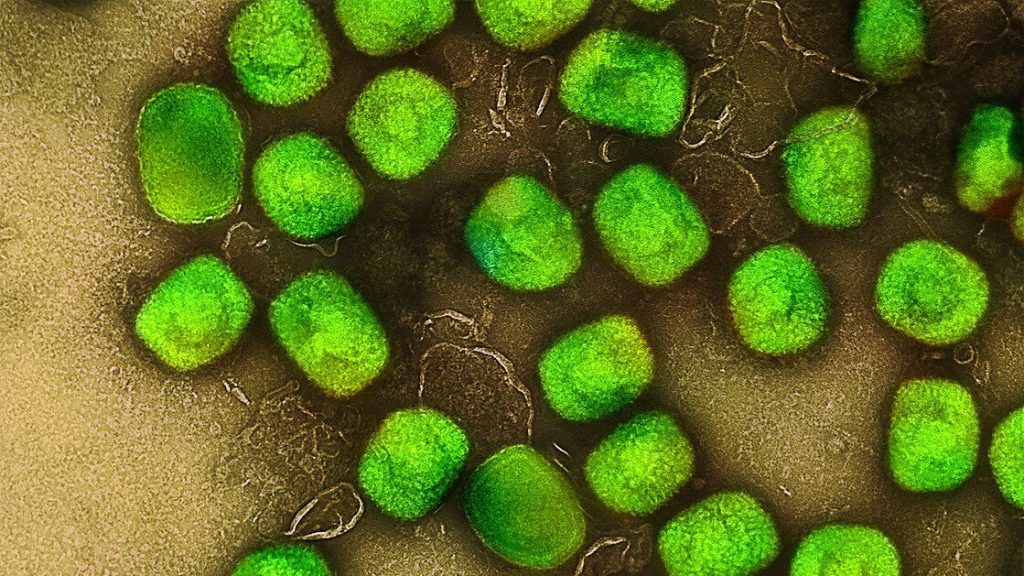

Individuals with schizophrenia have increased levels of dopamine in a region of the brain called the striatum. This region has two primary types of neurons: those with either D1 or D2 dopamine receptors.

Dopamine is a key for both receptors, but antipsychotics only block the D2 receptor locks. Therefore, experts have assumed these drugs preferentially act on neurons that express the D2 receptor locks. But, in fact, it was the other brain cells – the neighbouring ones in the striatum with D1 receptors – that responded to antipsychotic drugs in a manner that predicted clinical effect.

“The dogma has been that antipsychotic drugs preferentially affect striatal neurons that express D2 dopamine receptors,” Parker said. “However, when our team tested this idea, we found that how a drug affects the activity of D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons has little bearing on whether it is antipsychotic in humans. Instead, a drug’s effect on the other striatal neuron type, the one that expresses D1 dopamine receptors, is more predictive of whether they actually work.”

Schizophrenia is a debilitating brain disorder that affects approximately 1 in 100 people. While existing antipsychotics are effective for the hallmark symptoms of schizophrenia such as hallucinations and delusions, they are ineffective for the other symptoms of schizophrenia such as deficits in cognitive and social function.

Moreover, current antipsychotics are completely ineffective in more than 30% of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. The use of these drugs also is limited by their adverse effects, including tardive dyskinesia and parkinsonism.

The new study for the first time determined how antipsychotic drugs modulate the region of the brain thought to cause psychosis in living animals.

“Our study exposed our lack of understanding for how these drugs work and uncovered new therapeutic strategies for developing more effective antipsychotics,” Parker said.

Source: EurekAlert!