Cutting Edge Robotic Surgery: Beacons of Excellence at Two Cape Town Public Hospitals

By Biénne Huisman

Within South Africa’s beleaguered public health sector – unsettled by budget cuts, understaffing, and divisive NHI legislation – cutting edge surgical robots that have been used to perform more than 600 surgeries at two Cape Town public hospitals are beacons of excellence that offer a glimmer of hope. Spotlight’s Biénne Huisman visited Dr Tim Forgan at Tygerberg Hospital to learn more.

Cutting edge robotic surgery might not immediately come to mind when one thinks of public hospitals, but in a first for public healthcare in South Africa, such systems are being used at two hospitals in the Western Cape.

The da Vinci Xi systems enable surgeons to control operations from a console – steering three arms with steel “hands” equipped with tiny surgical instruments; plus a fourth arm bearing a video camera (the laparoscope). The system translates a surgeon’s hand movements in real time, with enhanced precision, range and visuals, compared to manual surgery.

“It really is next level, it feels like you’re inside the patient,” says colorectal specialist Dr Tim Forgan, Tygerberg Hospital’s da Vinci robotics coordinator. “With this technology we can operate so much finer. You can see ten times better with this robot than with the naked eye; you can see tiny, tiny nerves you wouldn’t normally see. And you can manoeuvre surgical instruments so much better. Because of that, people have way better function after the procedure.”

He explains that the technology allows major surgery to be completed through small incisions – instead of larger cuts made by a doctor’s hand – leading to less bleeding and a faster recovery time.

Over 600 surgeries in two years

Lorraine Gys from Phillipstown in the Northern Cape can attest. On 22 February 2022, the 65-year-old pensioner became the first patient to undergo da Vinci robotic surgery in South Africa’s public sector. Forgan was behind the console, at Tygerberg Hospital.

Gys tells Spotlight: “The next day the sisters offered to wash me, I said to them ‘no, I’m not helpless.’ My recovery was very quick. I was up and about in no time, while the other patients had to be assisted. I was discharged on day four, and back at home I could even continue doing my own chores.”

Two years later, Gys is cancer free. The mother of three, who now lives in Eerste River, recalls how she made news headlines: “Before the operation, Dr Forgan explained everything to me. They asked my permission, saying that media will be there and the [provincial health] minister.”

Indeed, on the day Forgan operated on Gys, removing a cancerous rectal tumour, he was joined in theatre by several onlookers including former Western Cape MEC of Health and Wellness Nomafrench Mbombo.

“Yes it was a circus,” says Forgan, laughing. “A whole bunch of people watching me operate, quite bloody nerve-wracking. Fortunately I’m experienced at having lots of students around watching; plus performing surgery is just so immersive, everything else fades out.”

On that day, also in the operating room was colorectal surgeon Dr Roger Gerjy, keeping an eye. “He’s a very well-known robotic surgeon; a Swedish surgeon who works in Dubai,” says Forgan. “And if there was a problem, Roger would’ve taken over. He was also there to impart tips and tricks: move the instrument like this, shape it like a hockey stick; because with the robot it’s like having your whole arm inside [the body]. He’d give me advice on what to do with my extra floating arm – where to place it and how to manipulate it – because remember you’re controlling three arms at a time.”

Since 2022, the da Vinci robots installed at Cape Town’s two tertiary hospitals: Groote Schuur and Tygerberg, have enabled over 600 minimally invasive surgeries – including colorectal operations, prostatectomies, cystectomies (bladder removal surgery), and gynaecological procedures to treat endometriosis.

A spokesperson for the Western Cape Ministry of Health and Wellness, under former MEC Mbombo, Luke Albert explains: “We can see the immense impact it has for patients and the health system. For example, a traditional open cystectomy patient would require three days of ICU stay, as well as two weeks of hospital stay to recuperate. During this time, on average, 42% of patients require blood transfusions and almost 20% need total parenteral nutrition (when a patient is fed intravenously). A patient undergoing robotic surgery for a cystectomy requires no ICU stay and goes straight to a general ward for no more than six days on average, with no blood transfusions needed.”

Where the money came from

Asked how the department was able to afford R40 million per system for these machines in the context of severe budget cuts, Albert says: “The purchase was applicable to 2021/22 and not the current financial year; with all provincial health departments currently managing the effects of budget cuts.”

Asked the same question, Forgan explains the investment derived from surplus budget discovered within the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic: “There was a surplus because certain services just couldn’t be done. I mean, for us, we couldn’t do elective surgery. And how state funding works; if you don’t spend your [provincial] budget within the financial year, it goes back to central government.”

What it looks like

On a Friday afternoon at Tygerberg Hospital, Forgan is guiding Spotlight along corridors and up grey linoleum stairs, to the theatre where the da Vinci system is used. Dressed in black surgical scrubs bearing his name and a cap; on his feet Forgan is wearing bright pink crocs. In passing, he waves hello to fellow healthcare staff.

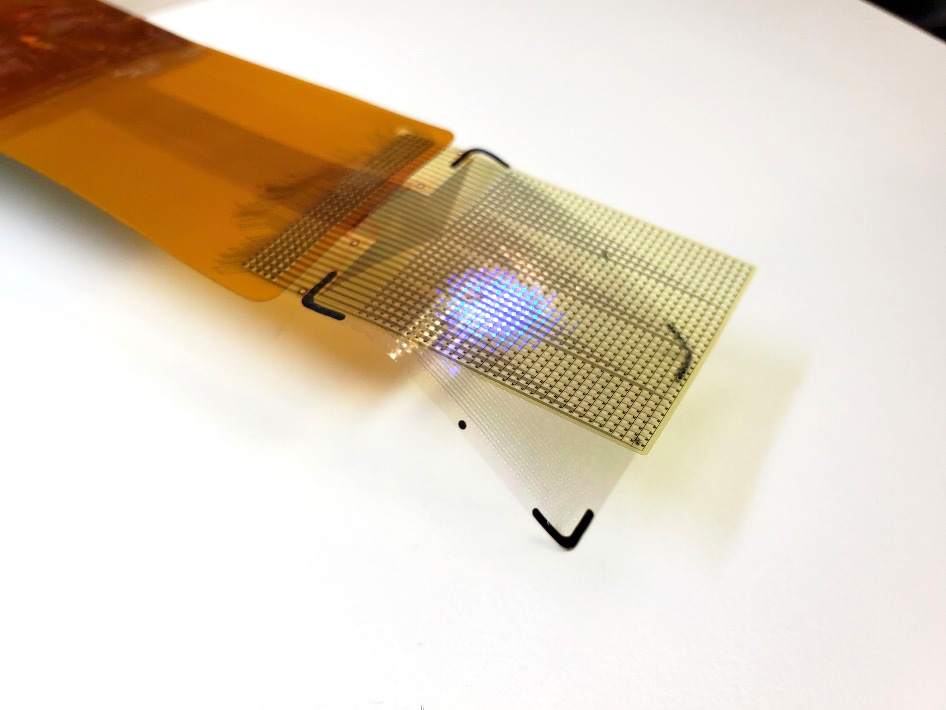

Inside the small blindingly white room, Forgan points out the three core components of the da Vinci system. There is a console with two control levers similar to refined joysticks – he demonstrates how to delicately hold them between forefingers and thumbs – a patient-side cart with four interactive metal arms (they are disposable; each arm can be used on twelve patients), and another trolley with a television screen. All connected by blue fibre optic cables.

As we speak, nurses arrive in the theatre, preparing it for upcoming gynaecology procedures scheduled for Monday. Forgan greets them, then continues to expand on his passion for colorectal surgery.

“With colorectal surgery, there’s a high rate of complications, but I really enjoy it, I really enjoy my job. When you have a successful outcome, saving a person from their cancer and prolonging their life through your intervention, that is the reward. Colorectal cancer is a very unpleasant disease, and operating like this can make one hell of a difference in a patient’s life.”

Colorectal cancer on the increase

Forgan adds that colorectal cancer is on the increase: “There aren’t many colorectal surgeons in South Africa, with a dire need for people to operate in this subspecialty. I mean, there are so few of us, we’re all on a WhatsApp group.”

Colorectal or colon cancer is the second most common cancer in South African men (following prostate cancer), and the third most common cancer in women (following breast and cervical cancer), according to the Cancer Association of South Africa.

Originally from Johannesburg, Forgan attended medical school at the University of the Witwatersrand. He qualified as a general surgeon at Stellenbosch University, sub-specialising in colorectal surgery at the University of Cape Town, before studying minimally invasive colorectal surgery at the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam.

He is also president of the South African Colorectal Society and runs a part-time private practise with his Tygerberg colleague, Dr Imraan Mia, at Cape Town’s Christiaan Barnard Hospital, where he has 32 all five-star Google reviews.

‘Early adopter’

Forgan considers himself an early adopter. But learning to use the da Vinci system did not happen overnight.

“We trained for ages,” he says. “On the surgical console there’s a simulator, so you spend hours and days and days doing procedures, over and over and over again. You have to get over 95% for each one of the procedures, before you can move on to the next skill.

“Then it’s how to use the machine, how to put it together, what to do if there’s an emergency; what if there’s a power failure and the machine stops working? How to safely remove it from the person. Then we went to the University of Lyon [in France] for two days of hands-on robotics training. And then a proctor – an international expert – comes to your theatre and does the procedures with you. So that was Dr Roger Gerjy, and that’s when we did Lorraine…”

First introduced by American biotechnology company Intuitive Surgical in 1999, the da Vinci Xi systems have sparked some liability lawsuits. An article from the Tampa Bay Times in February cites a lawsuit filed at the United States District Court in West Palm Beach, with a man claiming that a stray electrical arc from a surgical robot burned his wife’s small intestine during a colon cancer procedure, causing her death. The article quotes Intuitive Surgical’s 2023 financial report, which notes 8 606 da Vinci systems in use worldwide, having performed 2 286 000 procedures in 2023. The financial report mentions an undisclosed number of pending lawsuits, which the company disputes.

Nevertheless, Forgan remains an advocate.

Exiting via Tygerberg’s maze of corridors, he continues to reflect on his job. After our meeting, he is set to deliver a talk at the Cape Town International Convention Centre. His manner is earnest. Shrugging, he describes himself as a “glorified plumber”.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.