The Urgent Need for Early Detection Emphasised this Bone Marrow & Leukaemia Awareness Month

Leukaemia has been identified as the most prevalent cancer among the country’s youth, according to the latest report from the National Cancer Registry (NCR) of South Africa (2021). However, approximately half of children with cancer remain undiagnosed, with the majority of cases only being detected during the advanced stages of the illness. This is partly attributed to a lack of awareness of the early warning signs of childhood cancer.

As the world observes Bone Marrow & Leukaemia Awareness Month until the 15th of October, Dr Candice Hendricks, Paediatric Haematologist and Medical Spokesperson for DKMS Africa shares that leukaemia can be categorised as acute leukaemias or chronic leukaemias, each with varying symptoms. “Acute leukaemias are far more common in children and can further be divided into acute lymphoblastic- (ALL) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Among children, especially those aged between two and 10, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the most common blood cancer in this age group.

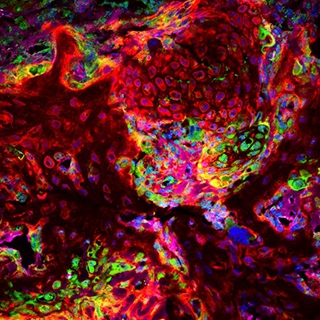

“This disease arises from genetic mutations in immature lymphocytes called lymphoblasts which are located in the bone marrow. The mutations lead to uncontrolled growth of these lymphoblasts,” she explains. “Lymphoblasts are abnormal blood stem cells that lose the ability to make mature blood cells. The uncontrolled growth of these cells in the bone marrow displaces normal blood cell development and leads to a decrease in properly functioning red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Patients may potentially present with an elevated white blood cell count on blood results, however, their impaired function leaves the body vulnerable to infections.”

Aligned with the NCR, Dr Hendricks emphasises that early symptoms often go unnoticed, as they mimic common, mild conditions, causing many patients and those who care for them to overlook them. “However, the severity of these symptoms escalates rapidly with acute leukaemias and persist even after standard treatment for infections. A high index of suspicion is required in diagnosing patients, and if any symptom persists, an immediate full blood count test is necessary, followed by additional tests if irregularities are detected.”

Prominent symptoms indicating the disease include:

- Blood clotting disorders or blood diathesis characterised by easy bruising from minor impacts and the appearance of small reddish spots on the skin. Other signs encompass blood in urine, as well as uncontrollable gum and nose bleeding.

- Muscle and joint pain, particularly in the limbs, along with frequent limb numbness.

- Fever and night sweats.

- Anaemia caused by a deficiency of red blood cells, leading to constant fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, lethargy, sleepiness, and pale skin.

- Recurrent infections that persist despite antibiotic treatment due to cancer cells impairing the immune system. Pathological cancer cells displace healthy leukocytes, rendering the body susceptible to various viral, bacterial, and fungal infections.

- Loss of appetite and weight loss.

- Enlarged lymph nodes.

- Stomach pain resulting from spleen and/or liver enlargement.

In support of Bone Marrow & Leukaemia Awareness Month, DKMS Africa continues to raise awareness and funds to cover the registration costs for as many potential stem cell donors as possible. Stem cell donations offer the best chance of survival for children afflicted by high-risk leukaemia which does not respond to or recurs after standard treatment. Answer the call! If you’re aged between 17 and 55 and in good general health, please register at https://www.dkms-africa.org/register-now. Registration is entirely free and takes less than five minutes.

For further information, get in touch with DKMS Africa at 0800 12 10 82.

About DKMS

DKMS is an international non-profit organisation dedicated to saving the lives of patients with blood cancer and blood disorders. Founded in Germany in 1991 by Dr. Peter Harf, DKMS and organisations of over 1,000 employees have since relentlessly pursued the aim of giving as many patients as possible a second chance at life. With over 11 million registered donors, DKMS has succeeded in doing this 100,000 times to date by providing blood stem cell donations to those in need. This accomplishment has led to DKMS becoming the global leader in the facilitation of unrelated blood stem cell transplants. The organisation has offices in Germany, the US, Poland, the UK, Chile and South Africa. In India, DKMS has founded the joint venture DKMS-BMST together with the Bangalore Medical Services Trust. International expansion and collaboration are key to helping patients worldwide because, like the organisation itself, blood cancer knows no borders.

DKMS is also heavily involved in the fields of medicine and science, with its own research unit focused on continually improving the survival and recovery rate of patients. In its high-performance laboratory, the DKMS Life Science Lab, the organisation sets worldwide standards in the typing of potential blood stem cell donors.