Adding Complex Milk Component to Infant Formula Confers Long-term Cognitive Benefits

Breastfeeding in infancy has been shown to confer cognitive and health benefits. For decades, researchers have sought to create a viable complement or alternative to breast milk to give children their best start for healthy development. New research out of the University of Kansas and published in the Journal of Pediatrics has shown how a complex component of milk that can be added to infant formula has been shown to confer long-term cognitive benefits, including measures of intelligence and executive function in children.

The research by John Colombo, KU Life Span Institute director and investigator, along with colleagues at Mead Johnson Nutrition and in Shanghai, China, adds to the growing scientific support for the importance of ingredients found in milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) in early human development.

The study showed that feeding infants formula supplemented with MFGM and lactoferrin for 12 months raised IQ by 5 points at 5 ½ years of age. The effects were most evident in tests of children’s speed of processing information and visual-spatial skills. Significant differences were also seen in children’s performance on tests of executive function, which are complex skills involving rule learning and inhibition.

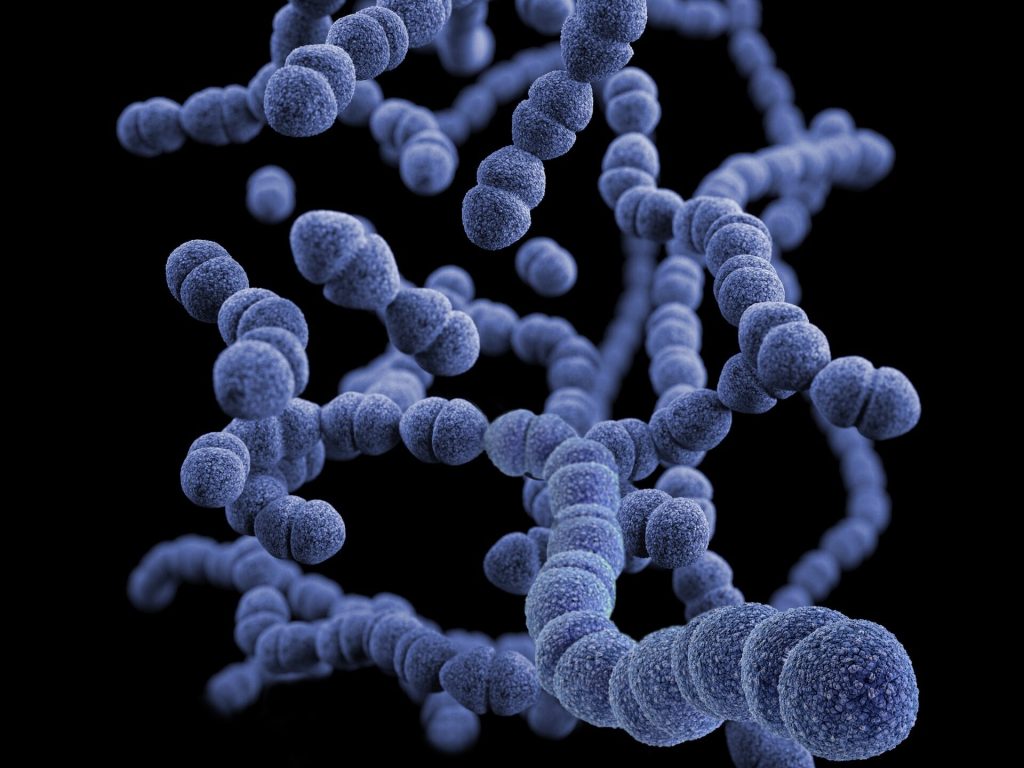

All forms of mammalian milk contain large fat globules that are surrounded by a membrane composed of a variety of nutrients important to human nutrition and brain development, Colombo said. When milk-based infant formula is manufactured, the membrane has typically been removed during processing.

“No one thought much about this membrane,” Colombo said, “until chemical analyses showed that it’s remarkably complex and full of components that potentially contribute to health and brain development.”

The 2023 study was a follow-up to a 2019 one also published in the Journal of Pediatrics, which showed that babies who were fed formula with added bovine MFGM and lactoferrin had higher scores on neurodevelopmental tests during the first year and on some aspects of language at 18 months of age.

The global nutrition research community has been looking at MFGM for about a decade, Colombo said. Because the membrane is made up of several different components, it isn’t known whether one of the components is responsible for these benefits, or whether the entire package of nutrients act together to improve brain and behavioural development.

These benefits were seen in children long after the end of formula feeding at 12 months of age.

“This is consistent with the idea that early exposure to these nutritional components contribute to the long-term structure and function of the brain,” said Colombo, who has spent much of his career researching the importance of early experience in shaping later development.

Source: University of Kansas