Common Eye Ointment can Damage Glaucoma Implants, Study Warns

Research shows that petrolatum-based eye ointments can cause the device to swell and potentially rupture, prompting an urgent update to clinical guidance.

Widely-used eye ointments can cause glaucoma implants to swell and potentially rupture, according to new research from Nagoya University in Japan. This study is the first to show, using clinical and experimental evidence, that petrolatum-based eye ointments can compromise the PRESERFLO® MicroShunt, an implant used in over 60 countries to treat glaucoma.

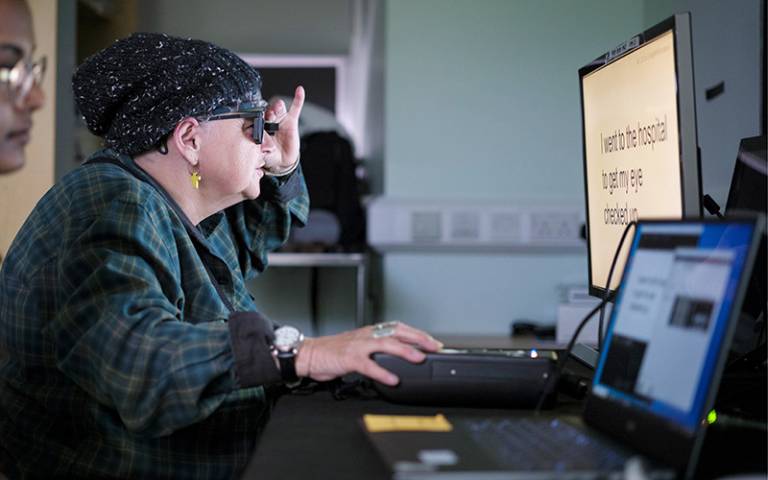

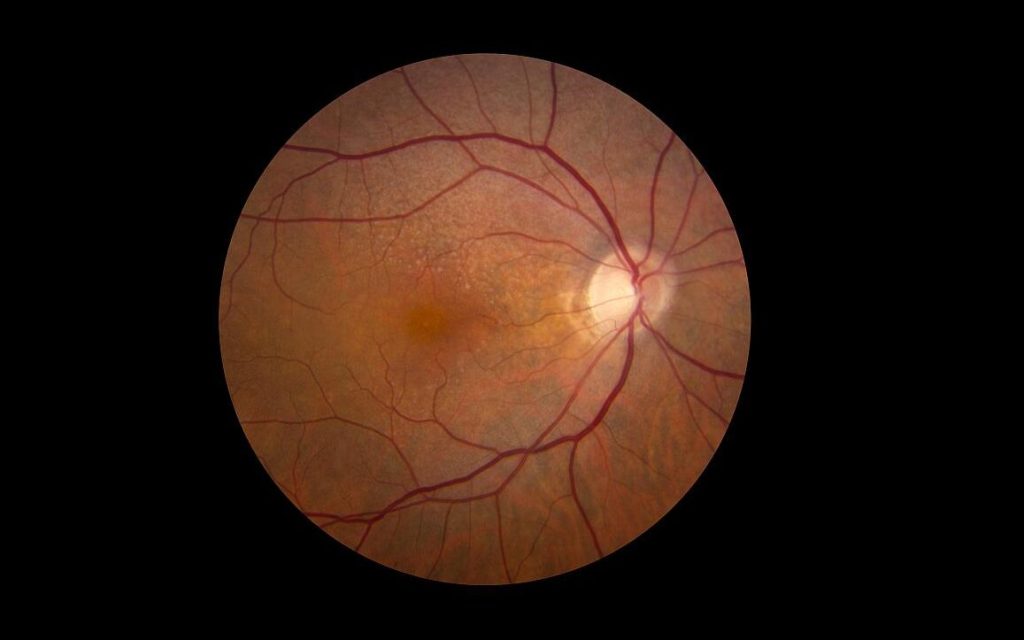

Glaucoma is an eye disease that damages the optic nerve and can lead to vision loss. It often results from increased intraocular pressure caused by blocked drainage of eye fluid. A recent study estimated that 76 million people globally are affected by glaucoma.

(Credit: Ryo Tomita)

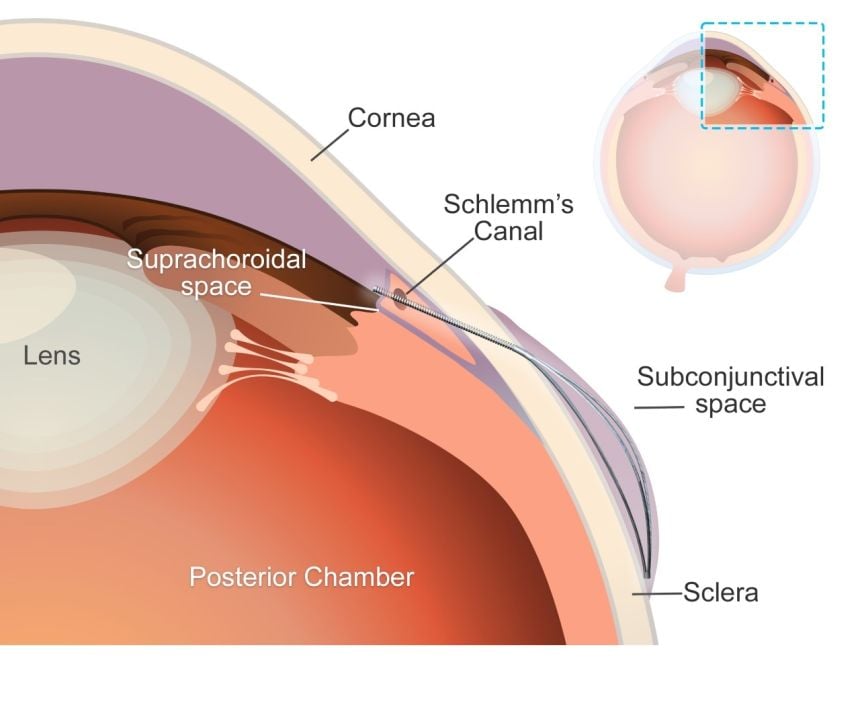

MicroShunt is a small filtration device implanted in the eye to improve fluid drainage in glaucoma patients. Compared to traditional surgeries, it lowers post-operative complications and reduces reliance on additional medications.

MicroShunt is made from a styrenic thermoplastic elastomer based on a polystyrene-block-polyisobutylene-block-polystyrene (SIBS) block polymer, which is highly biocompatible, flexible, and less likely to cause inflammation or scarring. However, this material is vulnerable when it comes into contact with hydrocarbon- and oil-based materials. Due to its high oil affinity, exposure to petrolatum-based eye ointments may allow oil components to penetrate the device, causing swelling and potential changes in its shape and flexibility.

The MicroShunt manufacturer’s instructions state that “the MicroShunt should not be subjected to direct contact with petrolatum-based (ie, petrolatum jelly) materials, such as ointments and dispersions.” But this precaution is not widely recognised or consistently followed in clinical practice.

“Swollen MicroShunts can be structurally fragile,” said ophthalmologist and Assistant Professor Ryo Tomita of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, the study’s first author. “During surgery, I observed a rupture in a swollen MicroShunt. If more clinicians are aware of this risk, they will be able to prevent similar problems.”

Tomita and colleagues, including Assistant Professor Taiga Inooka and Associate Professor Kenya Yuki from Nagoya University Hospital and the Graduate School of Medicine collaborated with Dr. Takato Kajita and Junior Associate Professor Atsushi Noro from the Graduate School of Engineering to examine changes in the MicroShunt after exposure to a petrolatum-based eye ointment.

The medical team reviewed clinical cases, while the engineering team conducted laboratory analyses. The findings were published in Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology.

Clinical evidence

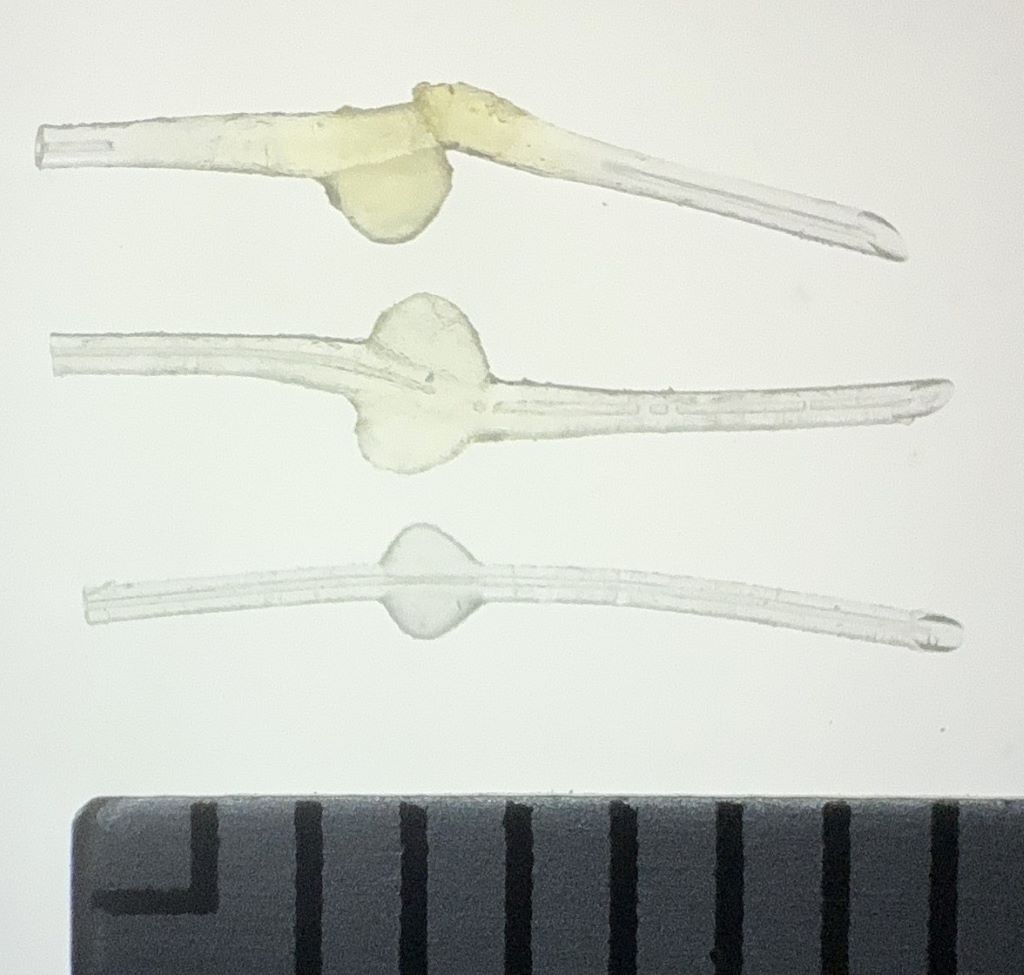

The clinical study examined seven glaucoma patients whose MicroShunt implants were later removed for different reasons. The results revealed a clear pattern. In three cases, the MicroShunt was exposed outside the conjunctiva, and patients received a petrolatum-based eye ointment. All three explanted devices showed significant swelling, and two of them ruptured.

In three other cases, the MicroShunt remained covered by the conjunctiva, and no ointment was administered. These devices retained their original structure. Crucially, in one additional case, the MicroShunt was exposed outside the conjunctiva, but no ointment was applied. The device did not swell. This indicates that direct contact with the ointment, rather than conjunctival rupture alone, is the primary cause of swelling.

Top: MicroShunt explanted from a patient, exhibiting diffuse swelling with fracture and loss of one fin

Middle: MicroShunt explanted from another patient, showing localized swelling around the fin

Bottom: Unused MicroShunt (control)

Scale: 1 division = 1 mm

(Credit: Ryo Tomita)

Laboratory confirmation

Laboratory experiments confirmed the clinical findings. The team immersed unused MicroShunts in petrolatum-based eye ointment to reproduce the swelling seen in clinical cases. Microscopic measurements showed significant changes. After 24 hours in the ointment, the MicroShunt’s outer diameter increased to 1.44 times its original size, and the fin-like portion widened to 1.29 times its initial value.

Chemical analysis identified the cause of this change. After 24 hours of immersion, oil components made up approximately 45% of the MicroShunt’s total weight, rising to 73% after three months. These results confirmed the primary cause of swelling to be the absorption of oil-based ointment constituents into the material.

Clinical implications

The research team emphasises that clinicians should avoid using petrolatum-based ointments on patients with MicroShunt implants, particularly when the device is exposed outside the conjunctiva. Alternative post-operative treatments should be considered, while further research is needed to assess whether swelling impacts MicroShunt performance even when rupture does not occur.

“Our study found that commonly used medical materials can cause unexpected complications if their chemical properties and usage environments are not fully understood,” Noro stated. “From both medical and engineering perspectives, we emphasise the importance of understanding the chemical properties of medical materials and appropriately managing their usage environments.”

Paper information:

Ryo Tomita, Taiga Inooka, Takato Kajita, Hideyuki Shimizu, Ayana Suzumura, Jun Takeuchi, Tsuyoshi Matsuno, Hidekazu Inami, Koji M. Nishiguchi, Atsushi Noro, and Kenya Yuki. (2026) Petrolatum-based ointment application induces swelling of the PRESERFLO MicroShunt. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology

DOI: 10.1007/s00417-025-07075-2