A Single Gene Causes Mitochondria to ‘Fragment’ in Obesity

While lifestyle factors like diet and exercise play a role in the development and progression of obesity, scientists have come to understand that obesity is also associated with intrinsic metabolic abnormalities. Now, researchers from University of California San Diego School of Medicine have shed new light on how obesity affects our mitochondria, the all-important energy-producing structures of our cells.

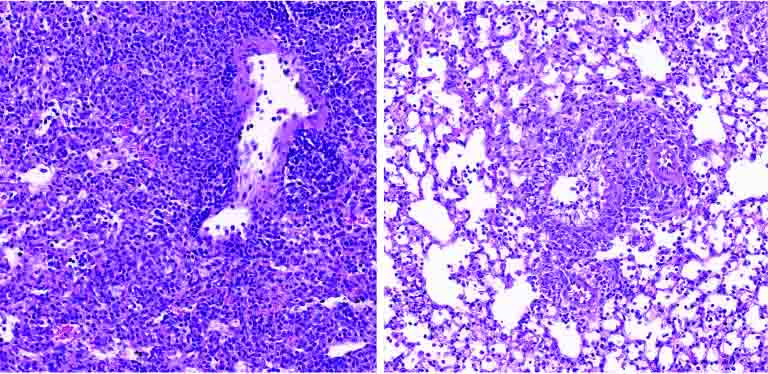

In a study published January 29, 2023 in Nature Metabolism, the researchers found that when mice were fed a high-fat diet, mitochondria within their fat cells broke apart into smaller mitochondria with reduced capacity for burning fat. Further, they discovered that this process is controlled by a single gene. By deleting this gene from the mice, they were able to protect them from excess weight gain, even when they ate the same high-fat diet as other mice.

“Caloric overload from overeating can lead to weight gain and also triggers a metabolic cascade that reduces energy burning, making obesity even worse,” said Alan Saltiel, PhD, professor in the Department of Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “The gene we identified is a critical part of that transition from healthy weight to obesity.”

Obesity occurs when the body accumulates too much fat, which is primarily stored in adipose tissue. Adipose tissue normally provides important mechanical benefits by cushioning vital organs and providing insulation. It also has important metabolic functions, such as releasing hormones and other cellular signaling molecules that instruct other tissues to burn or store energy.

In the case of caloric imbalances like obesity, the ability of fat cells to burn energy starts to fail, which is one reason why it can be difficult for people with obesity to lose weight. How these metabolic abnormalities start is among the biggest mysteries surrounding obesity.

To answer this question, the researchers fed mice a high-fat diet and measured the impact of this diet on their fat cells’ mitochondria, structures within cells that help burn fat. They discovered an unusual phenomenon. After consuming a high-fat diet, mitochondria in parts of the mice’s adipose tissue underwent fragmentation, splitting into many smaller, ineffective mitochondria that burned less fat.

In addition to discovering this metabolic effect, they also discovered that it is driven by the activity of single molecule, called RaIA. RaIA has many functions, including helping break down mitochondria when they malfunction. The new research suggests that when this molecule is overactive, it interferes with the normal functioning of mitochondria, triggering the metabolic issues associated with obesity.

“In essence, chronic activation of RaIA appears to play a critical role in suppressing energy expenditure in obese adipose tissue,” said Saltiel. “By understanding this mechanism, we’re one step closer to developing targeted therapies that could address weight gain and associated metabolic dysfunctions by increasing fat burning.”

By deleting the gene associated with RaIA, the researchers were able to protect the mice against diet-induced weight gain. Delving deeper into the biochemistry at play, the researchers found that some of the proteins affected by RaIA in mice are analogous to human proteins that are associated with obesity and insulin resistance, suggesting that similar mechanisms may be driving human obesity.

“The direct comparison between the fundamental biology we’ve discovered and real clinical outcomes underscores the relevance of the findings to humans and suggests we may be able to help treat or prevent obesity by targeting the RaIA pathway with new therapies,” said Saltiel “We’re only just beginning to understand the complex metabolism of this disease, but the future possibilities are exciting.”

Source: EurekAlert!