Time of Injury Matters: Circadian Rhythms Affect Muscle Repair

Circadian rhythms doesn’t just dictate when we sleep — it also determines how quickly our muscles heal. A new Northwestern Medicine study in mice, published in Science Advances, suggests that muscle injuries heal faster when they occur during the body’s natural waking hours.

The findings could have implications for shift workers and may also prove useful in understanding the effects of aging and obesity, said senior author Clara Peek, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

The study also may help explain how disruptions like jetlag and daylight saving time changes impact circadian rhythms and muscle recovery.

“In each of our cells, we have genes that form the molecular circadian clock,” Peek said. “These clock genes encode a set of transcription factors that regulate many processes throughout the body and align them with the appropriate time of day. Things like sleep/wake behaviour, metabolism, body temperature and hormones — all these are circadian.”

How the study was conducted

Previous research from the Peek laboratory found that mice regenerated muscle tissues faster when the damage occurred during their normal waking hours. When mice experienced muscle damage during their usual sleeping hours, healing was slowed.

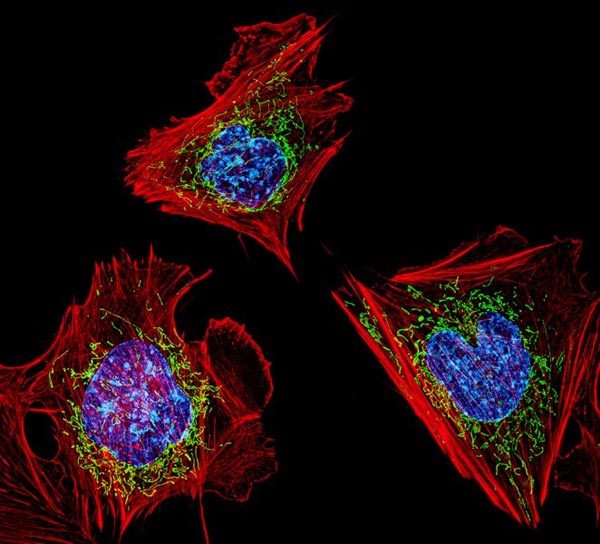

In the current study, Peek and her collaborators sought to better understand how circadian clocks within muscle stem cells govern regeneration depending on the time of day.

For the study, Peek and her collaborators performed single-cell sequencing of injured and uninjured muscles in mice at different times of the day. They found that the time of day influenced inflammatory response levels in stem cells, which signal to neutrophils — the “first responder” innate immune cells in muscle regeneration.

“We discovered that the cells’ signalling to each other was much stronger right after injury when mice were injured during their wake period,” Peek said. “That was an exciting finding and is further evidence that the circadian regulation of muscle regeneration is dictated by this stem cell-immune cell crosstalk.”

The scientists found that the muscle stem cell clock also affected the post-injury production of NAD+, a coenzyme found in all cells that is essential to creating energy in the body and is involved in hundreds of metabolic processes.

Next, using a genetically manipulated mouse model, which boosted NAD+ production specifically in muscle stem cells, the team of scientists found that NAD+ induces inflammatory responses and neutrophil recruitment, promoting muscle regeneration.

Why it matters

The findings may be especially relevant to understanding the circadian rhythm disruptions that occur in aging and obesity, Peek said.

“Circadian disruptions linked to aging and metabolic syndromes like obesity and diabetes are also associated with diminished muscle regeneration,” Peek said. “Now, we are able to ask: do these circadian disruptions contribute to poorer muscle regeneration capacity in these conditions? How does that interact with the immune system?”

What’s next

Moving forward, Peek and her collaborators hope to identify exactly how NAD+ induces immune responses and how these responses are altered in disease.

“A lot of circadian biology focuses on molecular clocks in individual cell types and in the absence of stress,” Peek said. “We haven’t had the technology to sufficiently look at cell-cell interactions until recently. Trying to understand how different circadian clocks interact in conditions of stress and regeneration, is really an exciting new frontier.”

Source: Northwestern University