Peacekeeper Cells Protect the Body from Autoimmunity During Infection

In the flurry of immune activity in an infection, immune cells need to be prevented from mistakenly attacking each other. New research from the University of Chicago shows how a specially trained population of immune cells keeps the peace by preventing other immune cells from attacking their own. The study, published in Science, provides a better understanding of immune regulation during infection and could provide a foundation for interventions to prevent or reverse autoimmune diseases.

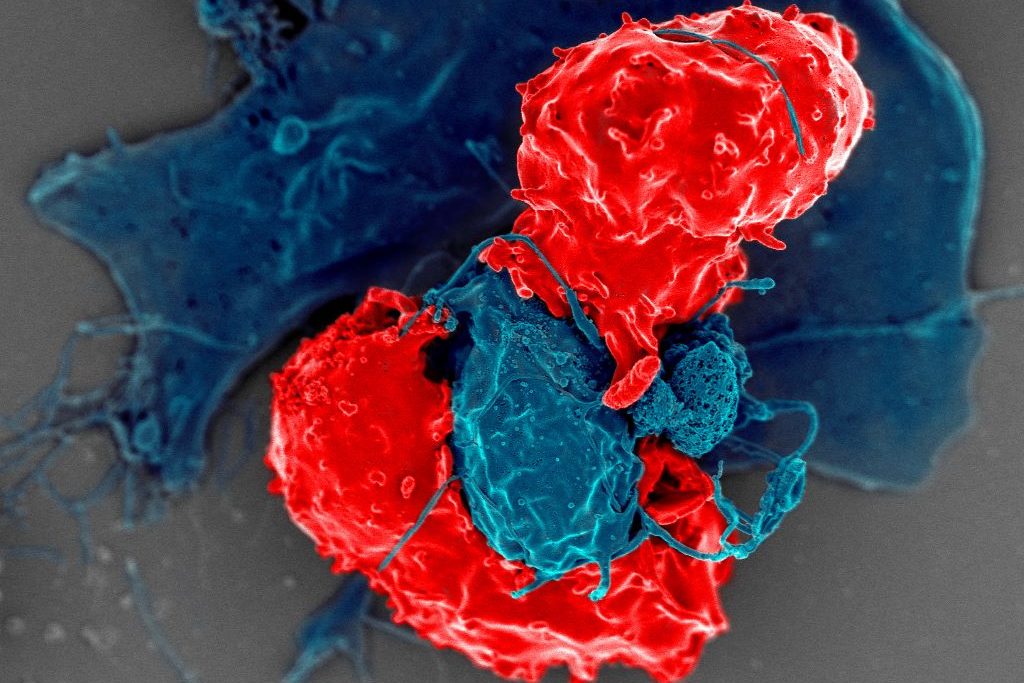

Several groups of white blood cells help coordinate immune responses. Dendritic cells take up proteins from foreign pathogens, chop them up into peptides called antigens, and display them on their surface. CD4+ conventional T (Tconv) cells, or helper T cells, inspect the peptides presented by dendritic cells. If the peptides are foreign antigens, the T cells expand in numbers and transform into an activated state, specialized to eradicate the pathogen. If the dendritic cell is carrying a “self-peptide,” or peptides from the body’s own tissue, the T cells are supposed to lay off.

During an autoimmune response, the helper T cells don’t distinguish between foreign peptide antigens and self-peptides properly and go on the attack no matter what. To prevent this from happening, another group of T cells called CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, are supposed to intervene and prevent friendly fire from the Tconv cells.

“You can think of them [Treg cells] as peacekeeper cells,” said Pete Savage, PhD, Professor of Pathology at UChicago and senior author of the new study. Tregs obviously do their job well most of the time, but Savage said that it has never been clear how they know when to intervene and prevent helper T cells from starting an autoimmune response, and when to hold back and let them fight an infection.

So, Savage and his team, led by David Klawon, PhD, a former graduate student in his lab who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), wanted to explore this property of the immune system, known in the field as self-nonself discrimination. T cells are produced in the thymus, a specialised organ of the immune system. During development, Treg cells are trained to recognise specific peptides, including self-peptides from the body. When dendritic cells present a self-peptide, the Treg cells trained to spot them intervene to stop helper T cells from getting triggered.

For the study, Savage and Klawon worked in close collaboration with co-first author Nicole Pagane, a graduate student at MIT, as well as co-corresponding authors Harikesh Wong at the Ragon Institute of the Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT and Harvard University, and Ron Germain at the National Institutes of Health.

T cell specificity is what the team found makes a crucial difference in self-nonself discrimination. The researchers experimentally depleted Treg cells in mice that were specific to a single self-peptide from the prostate. In healthy mice in the absence of infection, this change did not trigger autoimmunity to the prostate. When the researchers infected mice with a bacterium that expressed the prostate self-peptide, however, the absence of matched, prostate-specific Treg cells triggered prostate-reactive T helper cells and introduced autoimmunity to the prostate.

Interestingly though, this alteration did not impair the ability of helper T cells to control the bacterial infection by responding to foreign peptides.

“It’s like a doppelganger population of T cells. The CD4 helper cells that could induce disease by attacking the self share an equivalent, matched population of these peacekeeper Treg cells,” Savage said. “When we removed Treg cells reactive to a single self-peptide, the T helper cells reactive to that self-peptide were no longer controlled, and they induced autoimmunity.”

The root causes of autoimmune disease are a complex interaction of genetics, the environment, lifestyle, and the immune system. Classic, conventional thinking in the immunology field promoted the idea that the immune system establishes self-nonself discrimination by purging the body of helper T cells that are reactive to self-peptides, thereby preventing autoimmunity. Savage said this study shows that purging is inefficient though, and that specificity matching by Treg cells may be equally as important.

“The idea is that specificity matters, and for a fully healthy immune system, you need to have a good collection of these doppelganger Treg cells,” he said. As long as the immune system generates enough matched Treg cells, they can prevent autoimmune responses without impacting responses to infections.

“It’s like flipping the idea of self-nonself discrimination upside down. Instead of having to delete all helper T cells reactive to self-antigens, you simply generate enough of these Treg peacekeeper cells instead,” Savage said.

Source: University of Chicago