Pharmacists Can Treat People with HIV, Appeal Court Rules

“Legitimate and compelling public interests” to allow pharmacists to initiate antiretroviral treatment, says judge

The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) has dismissed, with costs, an appeal by a doctor’s organisation, the IPA Foundation, aimed at stopping specially trained pharmacists from treating people with HIV and TB.

The IPA first took its dispute with the South African Pharmacy Council (SAPC) to the Gauteng High Court in Pretoria. In 2023, Judge Elmarie van der Schyff ruled in favour of the pharmacists, giving a judicial go-ahead for the council to introduce its Pharmacy-Initiated Management of Antiretroviral Treatment (PIMART) initiative.

However the IPA Foundation, intent on having the initiative set aside, took this ruling on appeal to the SCA. In that court, five judges this week ruled against it. The ruling came nearly 11 months after the case was heard, far more than the three months that judicial norms provide for when a judgment is reserved.

Read the judgment

Justice Tati Makgoka, writing for the court, said the initiative was created in response to a persistent rise in new HIV infection rates.

The SAPC, at the department’s request, deemed PIMART suitable for addressing this issue.

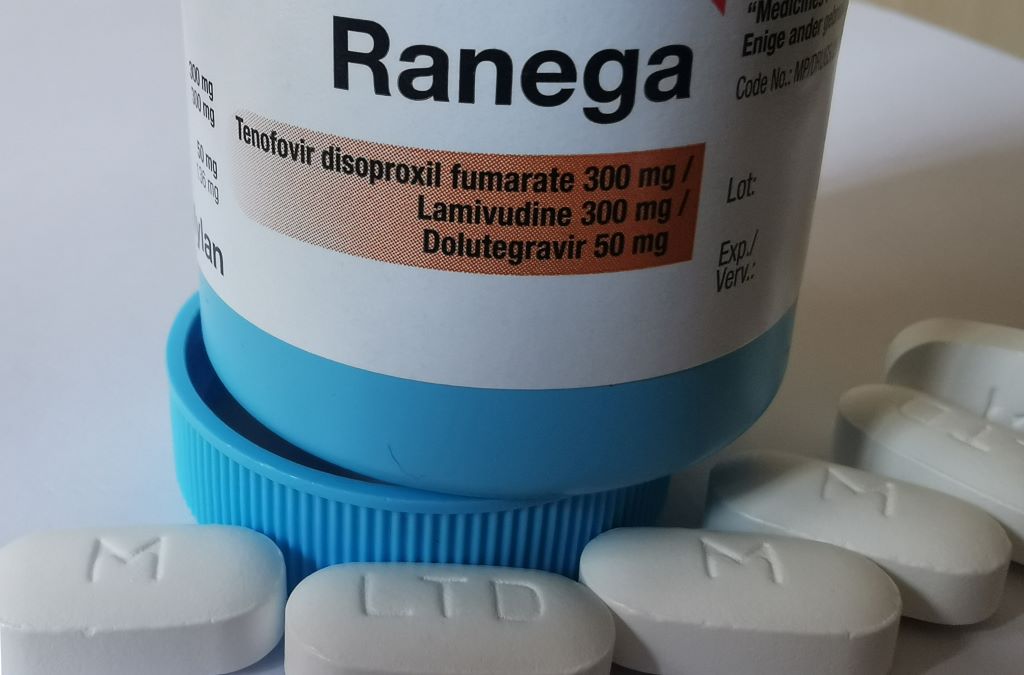

“As the high court correctly found, the SAPC evaluated the risks associated with pharmacists initiating first-line ART [antiretroviral treatment] and TPT [tuberculosis preventive therapy] as well as providing medicines for PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of HIV] and PEP [Post Exposure Prophylaxis of HIV], considering the risks when deciding to approve the PIMART training.

“The uncontested evidence presented by the SAPC demonstrates that the approved accreditation process for PIMART was rigorous and thorough,” Makgoka said.

In her previous judgment, Van Der Schyff had noted that a pilot project had emphasised the value of the initiative, which was in line with the World Health Organisation’s vision to promote widely accessible primary health care.

“The untapped value of pharmacists in fighting HIV was also emphasised by the efficient role pharmacies played in meeting health care needs and providing health care services during the Covid-19 pandemic,” she said.

“The need to widen access to first line ART and TPT therapy on a community level is not a figment of SAPC’s imagination but a dire need that is also evinced in other countries.”

The IPA Foundation had approached the Pretoria court, under the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA), seeking to review and set aside the SAPC’s decision to implement PIMART.

IPA claimed that the SAPC had failed to give interested parties an adequate opportunity to comment before the initiative was implemented. It further contended that PIMART unjustifiably encroached on the domain of medical practitioners and was in conflict with legislation.

On appeal, the IPA persisted with these arguments.

Dealing with the background, Justice Makgoka said the SAPC had published a notice in the government gazette in March 2021 regarding the proposed adoption of PIMART, giving interested parties 60 days to comment. This resulted in government approval later that year.

It was only after this that the IPA submitted its comments and objections.

Following engagements, the IPA lodged the review application in the high court.

On the issue that the IPA and its members claimed they were not given sufficient notice of PIMART, because it was advertised in the government gazette during the Covid-19 pandemic – Makgoka said there was no suggestion that the pandemic had “paralysed the administrative functions” of the IPA.

Remarkably, the judge said, the IPA had not suggested that the notice did not come to its attention, finding that adequate notice had been given. Makgoka said that several other organisations had submitted comments during the prescribed period.

He said the IPA had also not challenged the validity of the Pharmacy Act, which specified publication in the gazette and in the absence of that, it was not open for it to say the publication was inadequate.

Makgoka said the IPA had introduced the issue of “rationality” only in its notice of appeal. However, the court had dealt with this because there was no prejudice to the SAPC.

In ruling on this issue, he said PIMART was a crucial intervention in the public interest, which had been devised by a group of medical experts.

“Through PIMART, the SAPC aimed to improve access to healthcare. Contrary to the IPA’s contentions, PIMART is an essential intervention in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Its introduction constitutes a rational legislative and practical measure with the competence of the SAPC as an organ of the state in enhancing access to healthcare for HIV treatment, in fulfilment of the state’s obligation under the Constitution,” Makgoka said.

“These are legitimate and compelling public interests.”

He said the IPA was wrong in believing that PIMART was a blanket licence for pharmacists to treat HIV patients.

“Its scope is limited and applies only to accredited pharmacists. It will not alter the scope of practice for medical practitioners. The fact is that medical practitioners do not have the exclusive rights to care for people living with HIV/AIDS. This is a collaborative effort involving various health professionals.”

The IPA had also submitted that pharmacists were not authorised to prescribe schedule 3, 4 and 5 medicines without a prescription.

However, the judge said, the Medicines Act carved out an exception to this with authorisation of the Director-General. It was through this that PIMART-accredited pharmacists could apply for permits to prescribe schedule 3 – 5 substances.

The appeal was dismissed with costs.

Certainly not all doctors oppose the idea of pharmacists initiating patients with HIV on treatment: the South African HIV Clinicians Society stated: “We look forward to supporting the rollout of PIMART which will further contribute to South Africa’s HIV response and progress towards the 2030 target of eliminating HIV as a public health concern.”

Republished from GroundUp under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Read the original article.