What does it Mean for Health? SAMRC Experts Weigh in on Budget 2025

By Charles Parry, Funeka Bango, Tamara Kredo, Wanga Zembe, Michelle Galloway, Renee Street and Caradee Wright

While the 2025 national budget boosts health spending, researchers from the South African Medical Research Council stress the need for strong accountability measures. They also raise concerns about rising VAT and omissions related to US funding cuts and climate change.

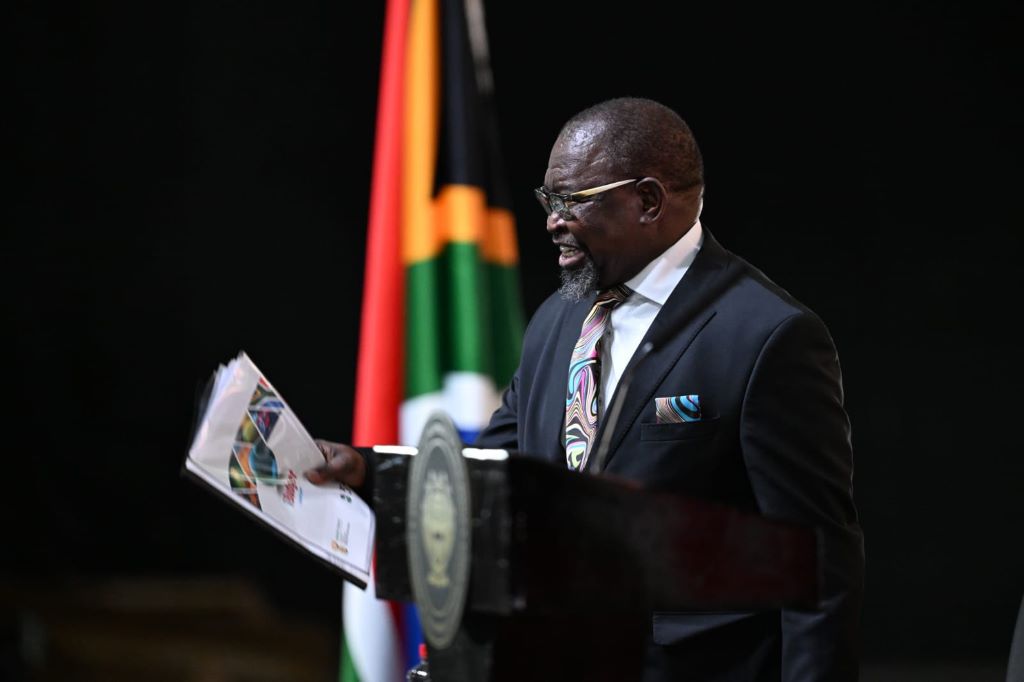

The 2025 budget speech by Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana saw a welcome boost to the health budget with an increased allocation from R277 billion in 2024/2025 to R329 billion in 2027/2028. This signals a government that is responding to the dire health needs of the public sector, that serves more than 80% of the South African population.

As researchers at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), we listened with interest and share our reflections on some of the critical areas of spend relevant for health and wellbeing.

We note the increase in investment in human resources for health and allocations for early childhood development and social grants. At the same time, we also raise concern about increasing VAT, with knock-on effects for the most vulnerable in our country. There were also worrying omissions in the speech, such as addressing the impact of the United States federal-funding freeze on healthcare services nationally, and a noticeable absence of comment on government’s climate-change plans.

Health and the link with social development: Recognising the importance of early childhood development

Education and specifically early childhood development (ECD) is known to have critical impacts on children’s health and wellbeing, with longstanding effects into youth and adulthood. In South Africa, eight million children go hungry every day, and more than a third of children are reported to live in households below the food poverty line, that is below the income level to meet basic food requirements, not even covering other basic essentials such as clothes.

While the increase in the number of registered ECDs is laudable, many more ECD centres in low-income areas remain unregistered, which means they do not get support from the government in terms of subsidies and oversight.

Social grants

The increase in social grants is welcomed. However, the marginal increase of the Child Support Grant (CSG) by only R30, from R530 to R560, is too little to impact on the high levels of child hunger and malnutrition. The release of the Child Poverty Review in 2023, which highlighted the eight million children going hungry every day, including CSG recipients, proposed the immediate increase of the CSG to at least the Food Poverty Line (R796 in 2024).

Social relief of distress still too small

The Social Relief of Distress (SRD) Grant is an important source of income for low-income, working-age, unemployed adults. Its continuance in 2025 is welcomed. However, it remains too small at R370 per person per month, and the stringent means-test criteria which disrupt continuous receipt from month-to-month, makes it an unreliable, unpredictable source of income for low-income individuals.

Strengthening the healthcare workforce

The Minister stated that “R28.9 billion is added to the health budget, mainly to keep about 9 300 healthcare workers in our hospitals and clinics”. It will also be used to employ 800 post-community service doctors, and to ensure that our pharmacies do not run out of medicines. The speech highlighted the necessary commitment to strengthening the healthcare system, specifically human resources for health.

Considering the pressures on resources, primarily due to the escalating disease burden and challenges within the health workforce, the proposed budget increase from R179 billion to R194 billion – an increase of 8.2% – to maintain the current workforce and employ additional healthcare workers signifies a positive step forward that will aid in addressing staff shortages.

However, this seems to fall short of what is needed to ensure all medical graduates are placed, and government’s own 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy.

VAT vs. health taxes

Despite the gains in health spending, the proposed increase in VAT raises substantial concerns to partially negate the potential benefits to the health sector. As the World Bank reports that approximately 60% of people living in South Africa live below the poverty line, increases to VAT will likely drive poverty levels higher.

A focus on other forms of taxation may be better, more evidence-based, and less likely to disproportionately affect those at the highest levels of poverty.

On the issue of alcohol taxes, often mischaracterised as “sin taxes” rather than “health taxes”, the Minister has proposed excise duties of 6.75% on most products for 2025/26. This is 2% above consumer inflation, which stands at 4.75%.

Raising alcohol prices through higher excise taxes is globally recognised as an effective way to address alcohol-related harms. National Treasury is to be commended for adjusting alcohol excise tax rates above CPI in the 2025/26 Budget. This is a move in the right direction, but it does not address the current anomalies in tax rates across different products. This failure to address shortcomings in the excise tax regime is expected, given the release of a discussion document on alcohol excise taxes in December 2024 with a February 2025 response date. The earliest we can expect substantial changes in excise tax rates is in February 2026.

From a public-health perspective, it makes sense to link alcohol excise taxes to the absolute alcohol content of the product to standardise across products. Ethanol is ethanol. The current differential in excise tax rates on different alcohol products is indefensible. Specifically, it makes no sense to tax wine and beer so much less than spirits in terms of absolute alcohol content. Wine, especially bag-in-box wine, is the cheapest product on the market in South Africa, and its affordability increases consumption, leading to more societal harm.

Beer is the most consumed product in the country and is increasingly sold in larger, non-resealable containers. A 2015 SAMRC study in Gauteng found the highest level of heavy episodic drinking with beer products, largely due to their affordability, especially in larger, non-resealable containers. Heavy episodic drinking is a major public-health concern in South Africa, with 43.0% of current drinkers engaging in heavy episodic drinking at least monthly, 50.9% of male and 30.3% of female drinkers. Increasing the excise tax on beer is a powerful tool that the state can use to reduce the level of such behaviour.

Additionally, it makes sense to have lower taxes on alcohol products with lower alcohol content, as this could shift consumption to less harmful products. The current excise tax regimen does not account for this within a single product type like beer or wine, as all products are taxed at the same rate regardless of their alcohol content.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw the benefits of decreased access to alcohol: fewer injuries, fewer unnatural deaths, and communities less disrupted by patrons visiting liquor outlets. While no one advocates for total liquor sales bans, increasing excise taxes on wine and beer would decrease alcohol consumption and reduce harms on drinkers, on others around them, and on society more broadly.

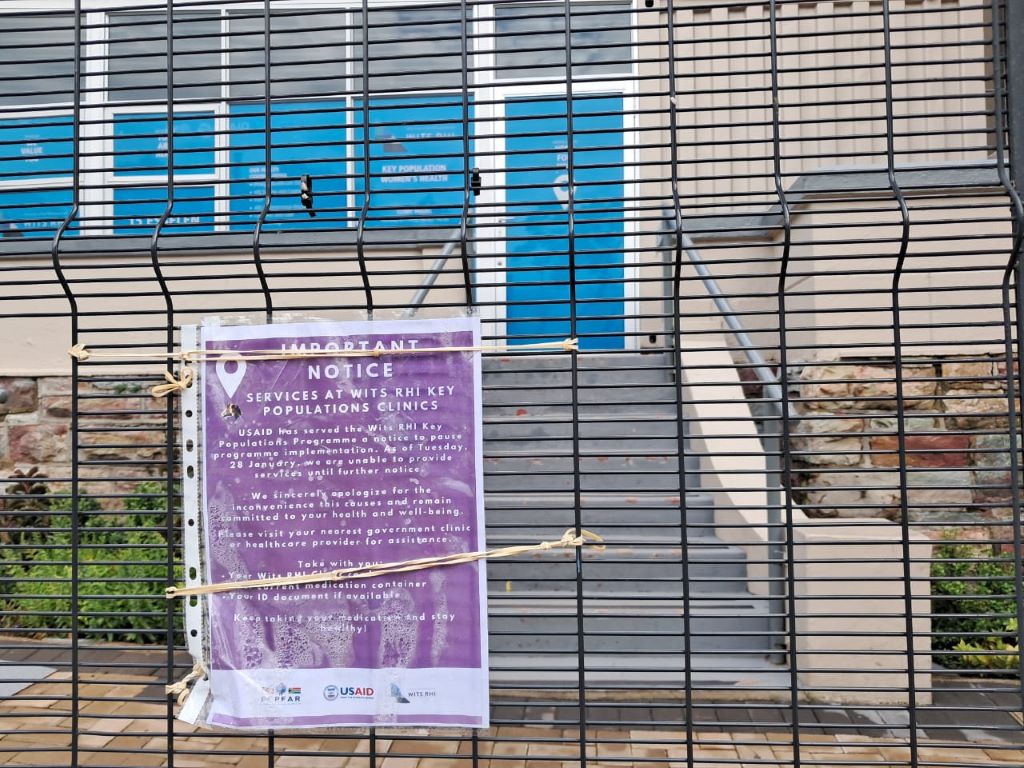

Acute risk to lives with knock on effects due to US federal funding cuts

We believe the South African government has a responsibility to step into the gap left by the sudden US federal funding freeze on HIV and TB services. The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) funds 17% of HIV and TB services in South Africa and covers salaries for thousands of health workers, including the vital services of community health workers.

The implications for people living with HIV and TB and affected by the externally funded services will be devastating. It will also have ripple effects on the health system as we see inevitable increases in demand for health services to address advancing illness, effects on families caring for ill relatives or losing income.

This area needs to be addressed and clear communication from the National Department of Health is urgently awaited. The US funding cuts clearly impact on essential research funding available to institutions like the SAMRC and no indication has been given in the budget of any plans to augment or replace such funding.

National Health Insurance for South Africa’s public sector

The Minister addressed budget allocations for NHI implementation, specifically, the mid-term indirect and direct conditional grants for NHI were R8.5 billion and R1.4 billion respectively. Although these amounts in themselves are minor compared to other health-budget allocations, allocations for infrastructure (R37.4 billion over the mid-term economic framework period) and additionally allocations for digital patient health information systems, chronic medicine dispensing and distribution systems, and medicine stock surveillance systems are vital for healthcare efficiency and improved outcomes.

Least said not soonest mended: climate change – ‘no comment’?

From a climate-crisis perspective, although the budget speech did not explicitly mention climate change or its related health challenges, there seems to be positive steps being taken to address these issues. Initiatives such as clean energy projects and efforts to improve water management have the potential to benefit all sectors of society, while helping to mitigate the health risks associated with climate change.

Promising spend on health, but who will measure the impact?

Ultimately, increasing health spend is a promising step to increase access to quality health services for South Africa’s population. However, this is not enough, government must seize the opportunity to translate the budget increase into improved health outcomes. The effectiveness of the additional funds must be maximised through efficiency, transparency, and sound governance. The government can reinforce the integrity of public-health services by aligning these increases with robust accountability measures.

Government-academic partnerships represent an opportunity to share knowledge, technical skills and resources to support evidence-informed decision-making for national health decision-making and strengthen monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. There are many examples of this working well, and we trust that the SAMRC, along with the network of higher education institutions are well placed to provide the necessary support.

*Parry, Bango, Kredo, Zembe, Galloway, Street and Wright are researchers with the SAMRC.

Note: Spotlight aims to deepen public understanding of important health issues by publishing a variety of views on its opinion pages. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily shared by the Spotlight editors.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.