X-chromosome Inactivation may Reduce Females’ Autism Risk

A study using mice published in the journal Cell Reports suggests how chromosome inactivation may protect women from autism disorder inherited from their father’s X chromosome.

Because cells do not need two copies of the X chromosome, the cells inactivate one copy early in embryonic development, a well-studied process known as X chromosome inactivation. As a result of this inactivation, every female is made up of a mix of cells, some have an active X chromosome from her father and others from her mother, a phenomenon known as mosaicism.

For many years, it has been thought that this was random and would result, on average, in a roughly 50/50 mix of cells, with 50% having an active paternal X chromosome and 50% an active maternal X chromosome.

Now a new study finds that, in the mouse brain at least, this is not the case. Instead, there appears to be a bias in the process that results in the paternal X chromosome being inactivated in 60% of the cells rather than the expected 50%.

When the X-linked mutation that is the most common cause of autism spectrum disorder is inherited from the father, the pattern of X-chromosome inactivation in the brain circuitry of females can prevent the effects of that mutation, the study found.

“This bias may be a way to reduce the risk of harmful mutations, which occur more frequently in male chromosomes,” said corresponding author Eric Szelenyi, acting assistant professor of biological structure at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

The X-chromosome is of particular interest because it carries more genes involved in brain development than any other chromosome. Mutations in the chromosome are linked to more than 130 neurodevelopmental disorders, including fragile X syndrome and autism.

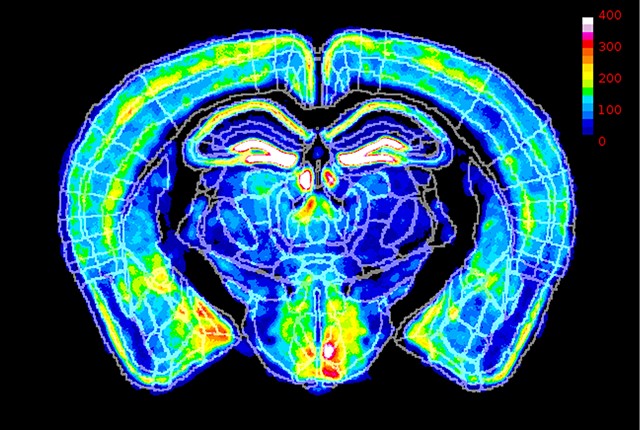

In the study, the researchers first determined the ratio of X chromosome inactivation in healthy mice by analyzing roughly 40 million brain cells per mouse. The scientists did this by using high-throughput volumetric imaging and automated counting. This analysis revealed a systematic 60:40 ratio across all possible anatomical regions.

They then examined what would happen if they genetically added a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. This syndrome is the most common form of inherited intellectual and developmental disability in humans.

They first tested the mice for behaviors thought to be analogous to those impaired in people with fragile X syndrome. These tests evaluate such things as their sensorimotor function, spatial memory and tendencies towards anxiety and sociability.

They found that the mice who inherited the mutation on their mother’s X chromosome, which are less likely to be inactivated in the 60:40 ratio, were more likely to exhibit behaviour analogous to fragile X syndrome. They exhibited more signs of anxiety, less sociability, poor performance in spatial learning, and deficits in sensorimotor function.

But mice that inherited the mutation from one their father’s X chromosomes, which were more likely to be inactivated, did not appear impaired.

“What was most interesting is that using each animal’s behavioural performance was most accurately predicted by X chromosome inactivation in brain circuits, rather than just looking at the brain as a whole, or single brain regions,” said Szelenyi. “This suggests that having more mutant X-active cells due to maternal inheritance increases overall disease risk, but specific mosaic pattern within brain circuitry ultimately decides which behaviors are impacted the most.”

“This suggests that the 20% difference in mutant X-active cells created by the bias can be protective against X mutations from the father, which occur more commonly,” he said.

The findings may also explain why symptoms of X-linked syndromes, like X-linked autism spectrum disorder, vary more in females than males.

Source: University of Washington