Tryptophan-rich Foods might Ease Colitis… and Braai Smoke may Help too

…although braai smoke still isn’t great for your lungs

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease that is prone to flareups, especially around feasts. New research in mice suggests that certain foods – especially those high in tryptophan, like turkey, pork, nuts and seeds – could reduce the risk of a colitis flare. It also helps explain why cigarette smokers are less likely to have colitis. The findings, published in Nature Communications, point to a noninvasive method of improving long-term colitis management, if the results are validated in people.

“Although there are some treatments for ulcerative colitis, not everyone responds to them,” says senior author Sangwon Kim, PhD, an assistant professor of immunology at Thomas Jefferson University.

“This disease has a huge impact on quality of life, and can lead to surgery to remove the colon or cancer.”

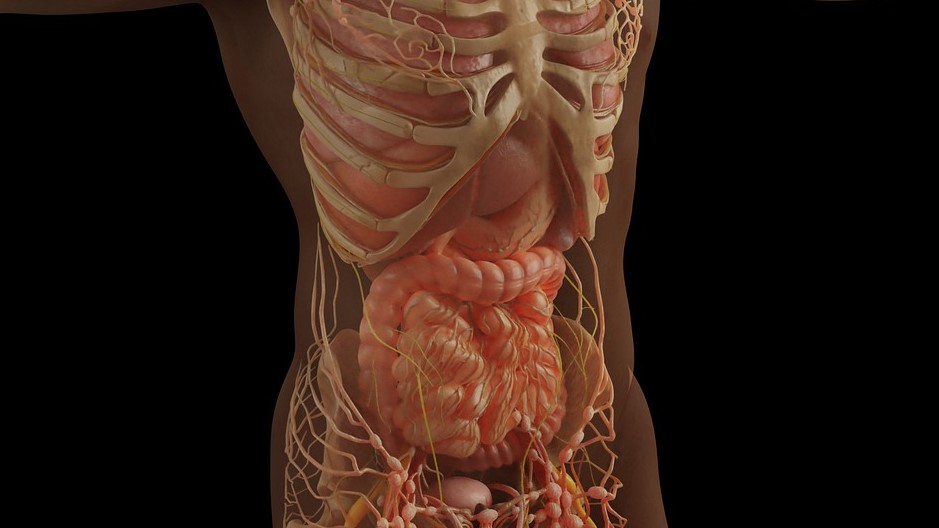

Since ulcerative colitis is caused by inflammation of the inner lining of the colon and rectum, Dr Kim and his colleagues looked for ways to calm the inflamed tissue.

They focused on a group of immune cells called T-regulatory (T-reg) cells, which can help break the cycle of inflammation. They reasoned that getting more T-reg cells to the colon might reduce the inflammation that causes colitis.

Dr Kim’s team thought about how to attract the T-reg cells, and found a specific receptor, CPR15, on the surface of T-reg cells that acts like a magnet for the colon. The more CPR15 the T-reg cells have, the more strongly they are attracted to the colon.

So they searched for molecules that could make T-reg cells produce more GPR15 to turn up the power of the magnet. They found tryptophan – specifically, one of the molecules that tryptophan breaks down into in the body – could increase these receptors called GPR15.

To test whether these molecules could control colitis, the researchers supplemented tryptophan in the diet of mice over a period of two weeks.

They saw a doubling in the amount of inflammation-suppressing T-reg cells in the colon tissue compared to mice that weren’t fed extra tryptophan.

Dr. Kim’s team also saw a reduction in colitis symptoms, which seemed to last for at least a week after tryptophan was removed from the diet.

“In human time that might translate to about a month of benefit,” explained Dr Kim.

However, when tryptophan was given to mice during a colitis flare, it provided little benefit, suggesting this dietary change might only be effective at preventing future flares rather than treating them.

In a chance finding, while looking for molecules that could increase GPR15, the researchers also stumbled across a molecule that helps explain why smoking seems to be protective against colitis. Researchers have long observed that people who smoke cigarettes have a lower incidence of ulcerative colitis than the general public.

Dr. Kim’s team found a molecule that is prevalent in smoke – from cigarettes and barbeque alike – that can also increase GPR15 levels on T-reg cells “Although both might help protect against colitis, tryptophan is obviously the much safer and healthier option,” says Dr Kim.

In the future, the researchers plan to test whether these results can be translated to people with colitis. Tryptophan supplement is considered safe, as long as the dose doesn’t exceed 100mg per day. Using the mouse data as a guide, Dr Kim expects that 100mg could be enough to see an effect in humans, and is planning further testing in clinical trials.

Source: Thomas Jefferson University