RSV Easier to Inactivate than Many Other Viruses

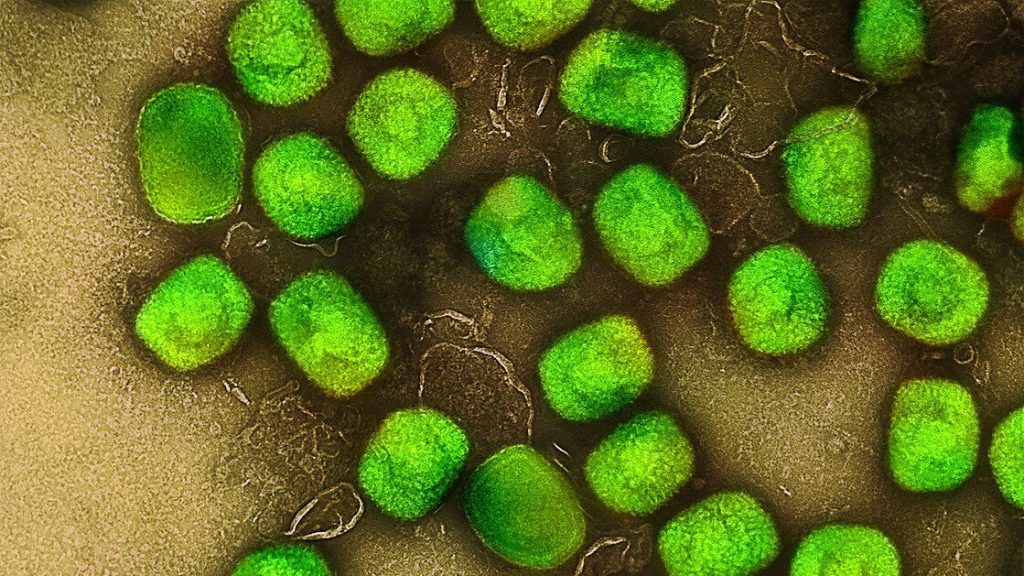

Every year, respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV) cause countless respiratory infections worldwide. For infants, young children and people with pre-existing conditions, the virus can be life-threatening and so clinicians are always on the look-out for ways to reduce infections. New research published in the Journal of Hospital Infection shows that, when used correctly, alcohol-based hand sanitisers and commercially available surface disinfectants provide good protection against transmission of the virus via surfaces.

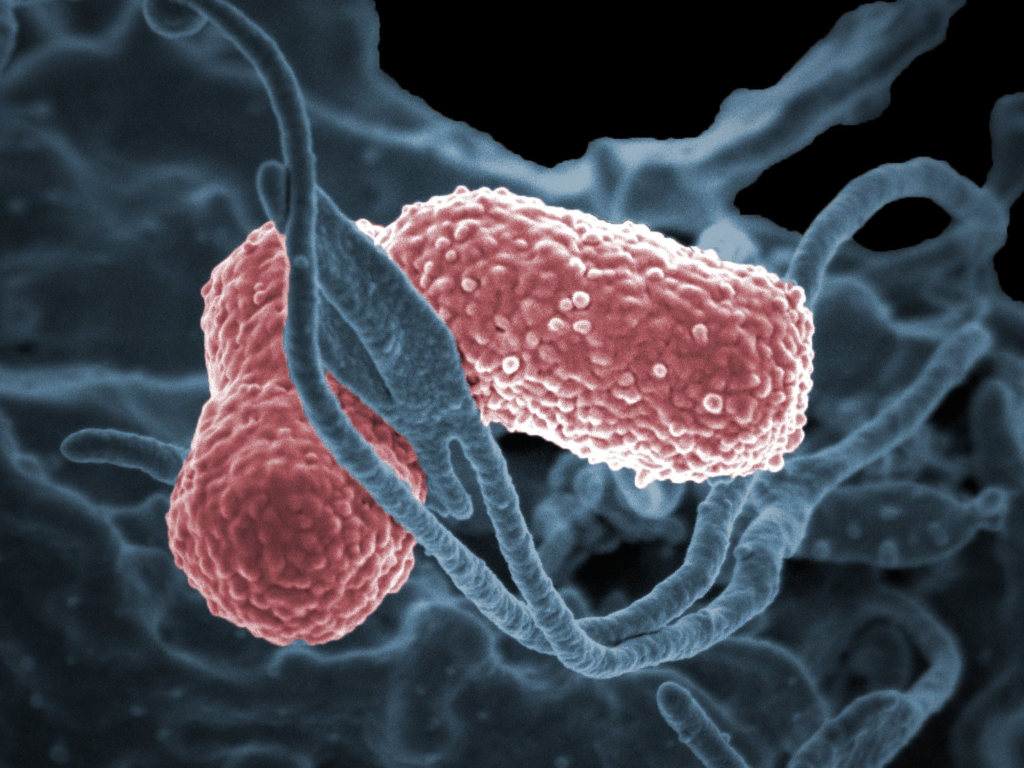

Some viruses are known to remain infectious for a long time on surfaces. To determine this period for RSV, the Ruhr-University Bochum virology team examined how long the virus persists on stainless steel plates at room temperature. “Even though the amount of infectious virus decreased over time, we still detected infectious viral particles after seven days,” says Dr Toni Luise Meister. “In hospitals and medical practices in particular, it is therefore essential to disinfect surfaces on a regular basis.” Five surface disinfectants containing alcohol, aldehyde and hydrogen peroxide were tested and found to effectively inactivate the virus on surfaces.

RSV is easier to inactivate than some other viruses

Hand sanitisers recommended by the WHO also showed the desired effect. “An alcohol content of 30 percent was sufficient: we no longer detected any infectious virus after hand disinfection,” said Toni Luise Meister. RSV is thus easier to render harmless than some other viruses, such as mpox (formerly monkeypox) virus or hepatitis B virus.

Still, most infections with RSV are transmitted from one person to another, via airborne droplets. The risk of contracting the virus from an infected person decreases if that person rinses their mouth for 30 seconds with a commercial mouthwash. The lab tests showed that three mouthwashes for adults and three of four mouthwashes designed specifically for children reduced the amount of virus in the sample to below detectable levels.

“If we assume that these results from the lab can be transferred to everyday life, we are not at the mercy of seasonal flu and common cold, but can actively prevent infection,” concludes Toni Luise Meister. “In addition to disinfection, people should wash their hands regularly, maintain a proper sneezing and coughing etiquette, and keep their distance from others when they’re experiencing any symptoms.”

Source: Ruhr-University Bochum