VZV Reactivation Is Driving CNS Infections

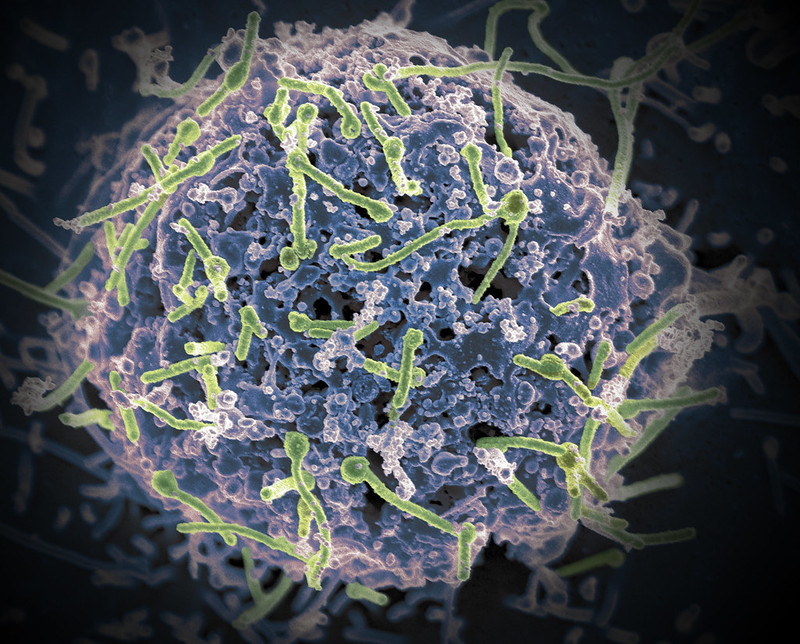

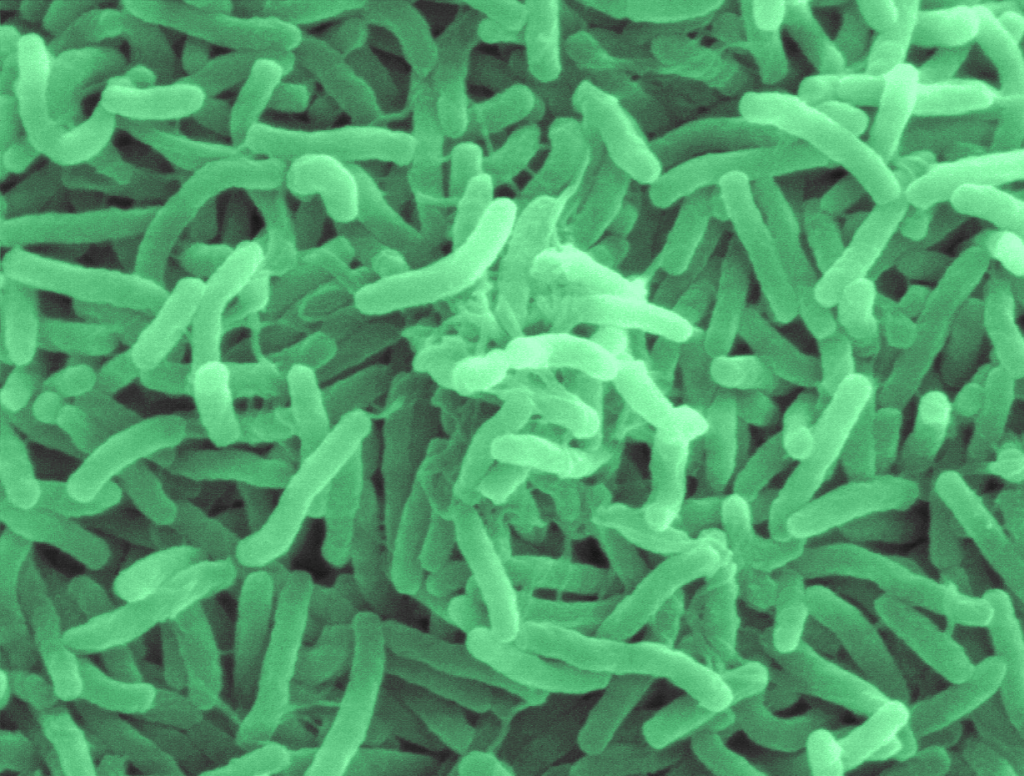

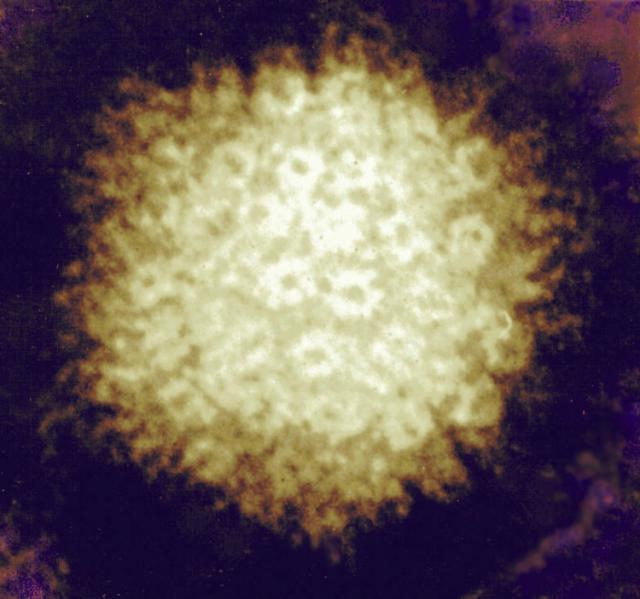

The varicella zoster virus (VZV), an infectious virus from the herpes virus family, is primarily known to cause varicella in children and shingles in adults. But lately, this virus has also been reported to trigger severe complications like central nervous system (CNS) infections. Researchers from Fujita Health University, Japan, conducted a comprehensive study spanning 10 years (2013–2022), to identify the VZV-related infections affecting the CNS. Their study reveals a marked increase in adult VZV-related CNS infections, particularly since 2019. The findings were published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The study was led by Professor Tetsushi Yoshikawa, along with Hiroki Miura and Ayami Yoshikane from the Department of Pediatrics, Fujita Health University School of Medicine. The researchers analysed cerebrospinal fluid samples of 615 adult patients with suspected CNS infections. VZV DNA was most frequently detected in these patients, with its presence in 10.2% of the cases, and aseptic meningitis being the most common infection.

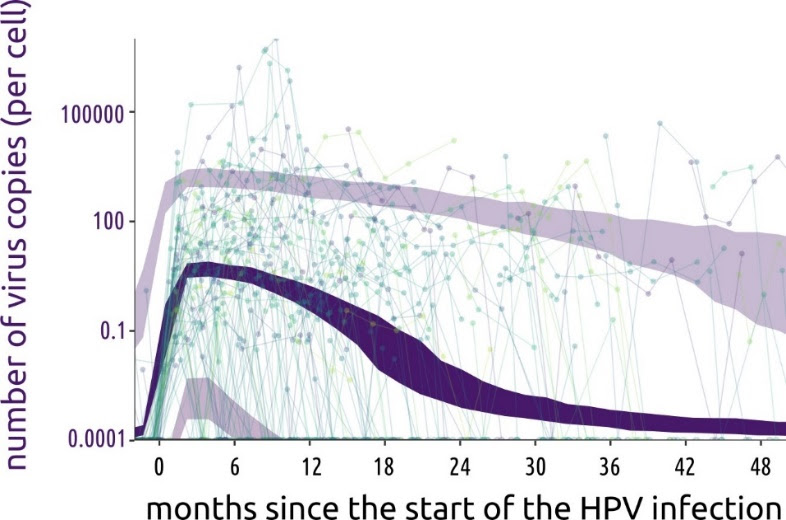

The data from 2019 to 2022 revealed that there was a noticeable rise in VZV DNA-positive cases, forming a distinct temporal cluster during this period. Professor Yoshikawa highlighted the results of the patient demographic analysis, reporting that “the proportion of aseptic meningitis increased from 50% between 2013 and 2018 to 86.8% between 2019 and 2022.” He further adds, “Similar to the rise in herpes zoster cases through VZV reactivation in the elderly, we believe this increase is also linked to VZV reactivation.”

The universal varicella vaccination, introduced in Japan in 2014, has reduced the natural booster effects from re-exposure to the virus. This potentially accelerates the immunity decline, leading to VZV reactivation, especially in cases like shingles. The researchers highlight the connection between the vaccination and the current scenario, saying, “The increase in VZV-induced CNS infections coincides with changes in varicella vaccination programs and emphasises the need for better preventive strategies.”

Furthermore, the researchers examined trends in VZV-induced CNS infection throughout the observation period using Kulldorff’s circular spatial scan statistics. As a result, it was confirmed that there was an accumulation of VZV-related CNS infections from 2019 to 2022. Although no direct causation was established, six patients did develop CNS infections after receiving COVID-19 vaccines.

“Further studies are needed to understand these interactions,” Yoshikawa notes. None of the eligible patients in this study had received the zoster vaccine, which was introduced in Japan in 2016. Increasing the number of VZV-related CNS infections underscores the importance of zoster vaccination in adults.

The research team stresses the broader implications of their findings, stating that the reactivation of VZV in the CNS is linked to an increased risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. They hypothesize, “If the prevention of VZV-related aseptic meningitis through herpes zoster vaccination is possible, these vaccinations could play a pivotal role in mitigating these risks of dementia.”

To address the growing concern, the research team advocates expanding public health initiatives to promote zoster vaccination among at-risk populations. “Our research underscores the necessity of proactive measures to prevent not just shingles, but also severe neurological complications associated with VZV,” explains Yoshikawa.

With the rise of the aging population and CNS infections, the study calls for urgent action to evaluate and implement comprehensive vaccination strategies to prevent CNS infections in the future.

Source: Fujita Health University