Intermuscular Fat Raises the Risk of Heart Attack or Failure

People with intermuscular fat are at a higher risk of dying or being hospitalised from a heart attack or heart failure, regardless of their body mass index, according to research published in the European Heart Journal.

This intermuscular fat is highly prized in beef steaks for cooking but little is known about it in humans, and its impact on health. This is the first study to comprehensively investigate the effects of fatty muscles on heart disease.

The new finding adds evidence that existing measures, such as body mass index or waist circumference, are not adequate to evaluate the risk of heart disease accurately for all people.

The new study was led by Professor Viviany Taqueti, Director of the Cardiac Stress Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA. She said: “Obesity is now one of the biggest global threats to cardiovascular health, yet body mass index – our main metric for defining obesity and thresholds for intervention – remains a controversial and flawed marker of cardiovascular prognosis. This is especially true in women, where high body mass index may reflect more ‘benign’ types of fat.

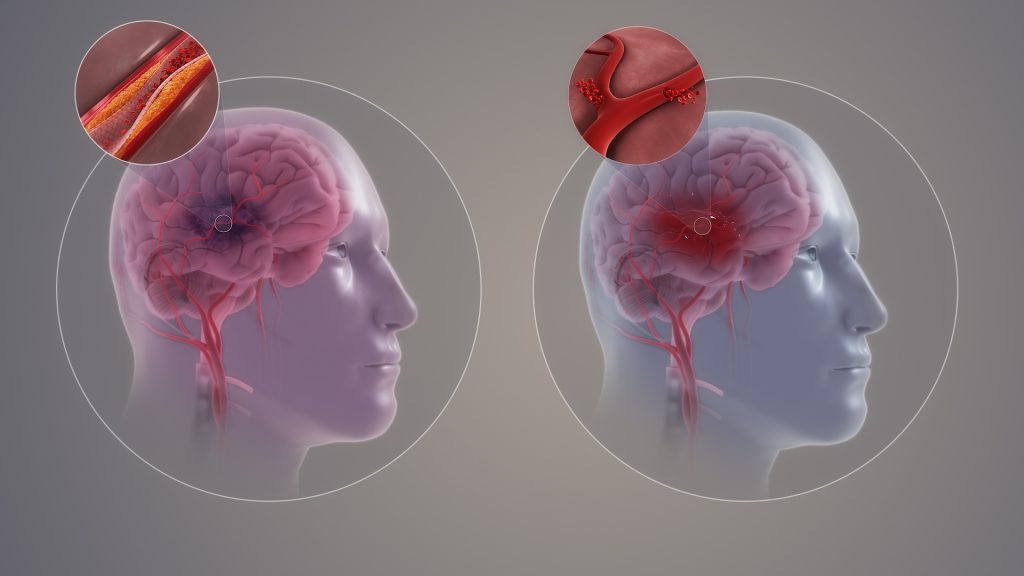

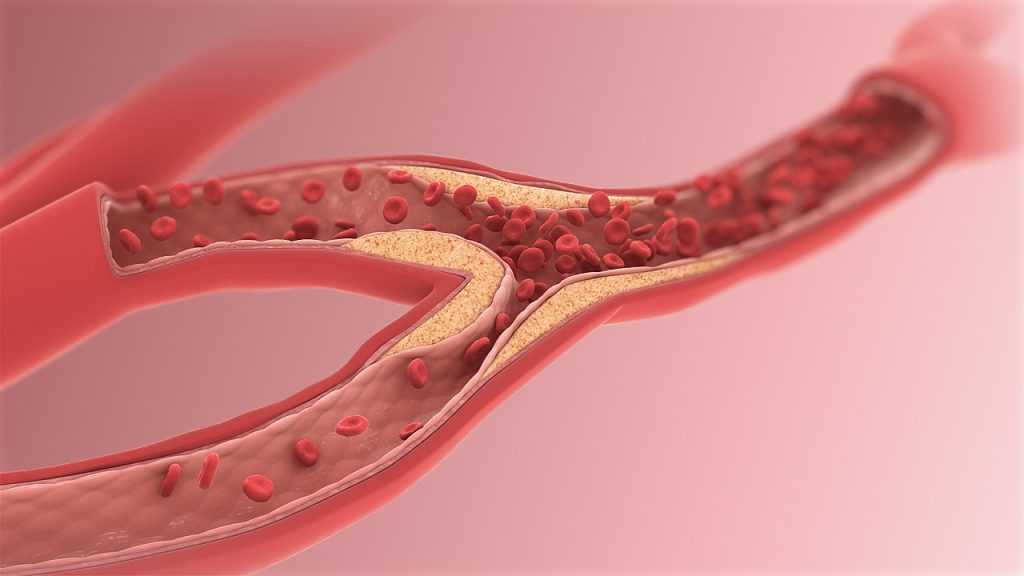

“Intermuscular fat can be found in most muscles in the body, but the amount of fat can vary widely between different people. In our research, we analyse muscle and different types of fat to understand how body composition can influence the small blood vessels or ‘microcirculation’ of the heart, as well as future risk of heart failure, heart attack and death.”

The new research included 669 people who were being evaluated at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for chest pain and/or shortness of breath and found to have no evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease (where the arteries that supply the heart are becoming dangerously clogged). These patients had an average age of 63. The majority (70%) were female and almost half (46%) were non-white.

All the patients were tested with cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning to assess how well their hearts were functioning. Researchers also used CT scans to analyse each patient’s body composition, measuring the amounts and location of fat and muscle in a section of their torso.

To quantify the amount of fat stored within muscles, researchers calculated the ratio of intermuscular fat to total muscle plus fat, a measurement they called the fatty muscle fraction.

Patients were followed up for around six years and researchers recorded whether any patients died or were hospitalised for a heart attack or heart failure.

Researchers found that people with higher amounts of fat stored in their muscles were more likely to have damage to the tiny blood vessels that serve the heart (coronary microvascular dysfunction or CMD), and they were more likely to go on to die or be hospitalised for heart disease. For every 1% increase in fatty muscle fraction, there was a 2% increase in the risk of CMD and a 7% increased risk of future serious heart disease, regardless of other known risk factors and body mass index.

People who had high levels of intermuscular fat and evidence of CMD were at an especially high risk of death, heart attack and heart failure. In contrast, people with higher amounts of lean muscle had a lower risk. Fat stored under the skin (subcutaneous fat) did not increase the risk.

Professor Taqueti said: “Compared to subcutaneous fat, fat stored in muscles may be contributing to inflammation and altered glucose metabolism leading to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. In turn, these chronic insults can cause damage to blood vessels, including those that supply the heart, and the heart muscle itself.

“Knowing that intermuscular fat raises the risk of heart disease gives us another way to identify people who are at high risk, regardless of their body mass index. These findings could be particularly important for understanding the heart health effects of fat and muscle-modifying incretin-based therapies, including the new class of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

“What we don’t know yet is how we can lower the risk for people with fatty muscles. For example, we don’t know how treatments such as new weight-loss therapies affect fat in the muscles relative to fat elsewhere in the body, lean tissue, and ultimately the heart.”

Professor Taqueti and her team are assessing the impact of treatments strategies including exercise, nutrition, weight-loss drugs or surgery, on body composition and metabolic heart disease.

In an accompanying editorial, Dr Ranil de Silva from Imperial College London and colleagues said: “Obesity is a public health priority. Epidemiologic studies clearly show that obesity is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, though this relationship is complex.

“In this issue of the Journal, Souza and colleagues hypothesise that skeletal muscle quantity and quality associate with CMD and modify its effect on development of future adverse cardiovascular events independent of body mass index (BMI).

“In this patient population who were predominantly female and had a high rate of obesity, the main findings were that increasing levels of intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) were associated with a greater occurrence of CMD, and that the presence of both elevated IMAT and CMD was associated with the highest rate of future adverse cardiovascular events, with this effect being independent of BMI.

“The interesting results provided by Souza et al are hypothesis generating and should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. This is a retrospective observational study. Whilst a number of potential mechanisms are suggested to explain the relationship between elevated IMAT and impaired coronary flow reserve, these were not directly evaluated. In particular, no details of circulating inflammatory biomarkers, insulin resistance, endothelial function, diet, skeletal muscle physiology, or exercise performance were given.

“The data presented by Souza et al. are intriguing and importantly further highlight patients with CMD as a population of patients at increased clinical risk. Their work should stimulate further investigation into establishing the added value of markers of adiposity to conventional and emerging cardiac risk stratification in order to identify those patients who may benefit prognostically from targeted cardiometabolic interventions.”

Source: European Society of Cardiology