An Experimental Drug to Prevent Post-heart Attack Heart Failure

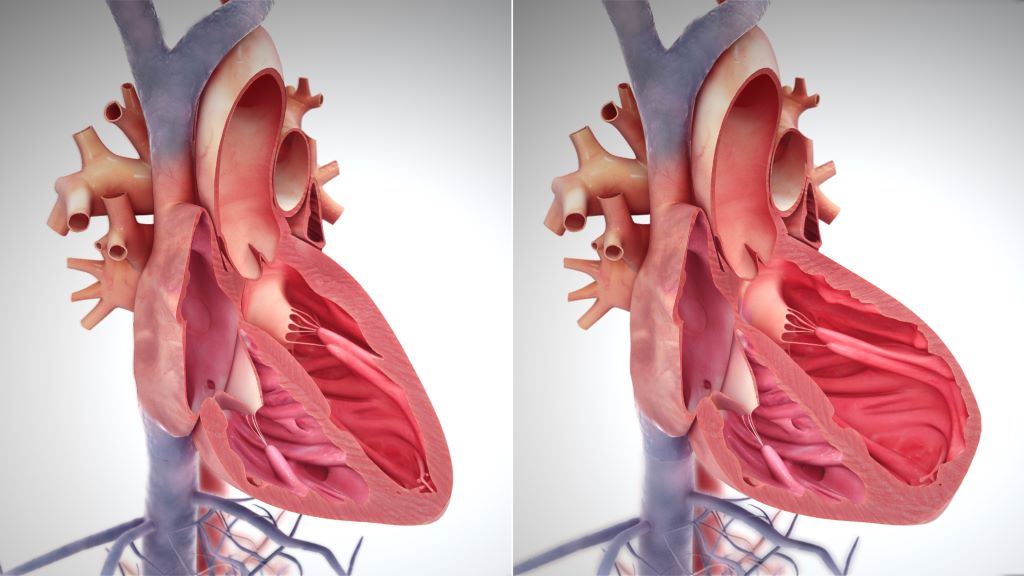

Scientists at UCLA have developed a first-of-its-kind experimental therapy that has the potential to enhance heart repair following a heart attack, preventing the onset of heart failure. After a heart attack, the heart’s innate ability to regenerate is limited, causing the muscle to develop scars to maintain its structural integrity. This inflexible scar tissue, however, interferes with the heart’s ability to pump blood, leading to heart failure in many patients – 50% of whom do not survive beyond five years.

The new therapeutic approach aims to improve heart function after a heart attack by blocking a protein called ENPP1, which is responsible for increasing the inflammation and scar tissue formation that exacerbate heart damage. The findings, published in Cell Reports Medicine, could represent a major advance in post-heart attack treatment.

The research was led by senior author Dr Arjun Deb, a professor of medicine and molecular, cell and developmental biology at UCLA.

“Despite the prevalence of heart attacks, therapeutic options have stagnated over the last few decades,” said Deb, who is also a member of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center. “There are currently no medications specifically designed to make the heart heal or repair better after a heart attack.”

The experimental therapy uses a therapeutic monoclonal antibody engineered by Deb and his team. This targeted drug therapy is designed to mimic human antibodies and inhibit the activity of ENPP1, which Deb had previously established increases in the aftermath of a heart attack.

The researchers found that a single dose of the antibody significantly enhanced heart repair in mice, preventing extensive tissue damage, reducing scar tissue formation and improving cardiac function. Four weeks after a simulated heart attack, only 5% of animals that received the antibody developed severe heart failure, compared with 52% of animals in the control group.

This therapeutic approach could become the first to directly enhance tissue repair in the heart following a heart attack; an advantage over current therapies that focus on preventing further damage but not actively promoting healing. This can be attributed to the way the antibody is designed to target cellular cross-talk, benefitting multiple cell types in the heart, including heart muscle cells, the endothelial cells that form blood vessels, and fibroblasts, which contribute to scar formation.

Initial findings from preclinical studies also show that the antibody therapy safely decreased scar tissue formation without increasing the risk of heart rupture – a common concern after a heart attack. However, Deb acknowledges that more work is needed to understand potential long-term effects of inhibiting ENPP1, including potential adverse effects on bone mass or bone calcification.

Deb’s team is now preparing to move this therapy into clinical trials. The team plans to submit an Investigational New Drug, or IND, application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration this winter with the goal of beginning first-in-human studies in early 2025. These studies will be designed to administer a single dose of the drug in eligible individuals soon after a heart attack, helping the heart repair itself in the critical initial days after the cardiac event.

While the current focus is on heart repair after heart attacks, Deb’s team is also exploring the potential for this therapy to aid in the repair of other vital organs.

“The mechanisms of tissue repair are broadly conserved across organs, so we are examining how this therapeutic might help in other instances of tissue injury,” said Deb, who is also the director of the UCLA Cardiovascular Research Theme at the David Geffen School of Medicine. “Based on its effect on heart repair, this could represent a new class of tissue repair-enhancing drugs.”