Sound is known to suppress the sensation of pain, and now scientists have identified the neural mechanisms through which sound blunts pain in mice. The findings, which could inform development of safer methods to treat pain in humans, were published in Science.

“We need more effective methods of managing acute and chronic pain, and that starts with gaining a better understanding of the basic neural processes that regulate pain,” said the director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), Rena D’Souza, DDS, PhD. “By uncovering the circuitry that mediates the pain-reducing effects of sound in mice, this study adds critical knowledge that could ultimately inform new approaches for pain therapy.”

Studies as far back as 1960, have shown that music and other kinds of sound can help alleviate acute and chronic pain in humans, including pain from dental and medical surgery, labour and delivery, and cancer. Yet the mechanism behind this remained elusive.

“Human brain imaging studies have implicated certain areas of the brain in music-induced analgesia, but these are only associations,” said co-senior author Yuanyuan (Kevin) Liu, PhD, at NIDCR. “In animals, we can more fully explore and manipulate the circuitry to identify the neural substrates involved.”

The researchers first exposed mice with inflamed paws to three types of sound: a pleasant piece of classical music, an unpleasant rearrangement of the same piece, and white noise. Surprisingly, all three types of sound, when played at a low intensity relative to background noise (about the level of a whisper) reduced pain sensitivity in the mice. Higher volume had no effect on their pain sensitivity.

“We were really surprised that the intensity of sound, and not the category or perceived pleasantness of sound would matter,” Dr Liu said.

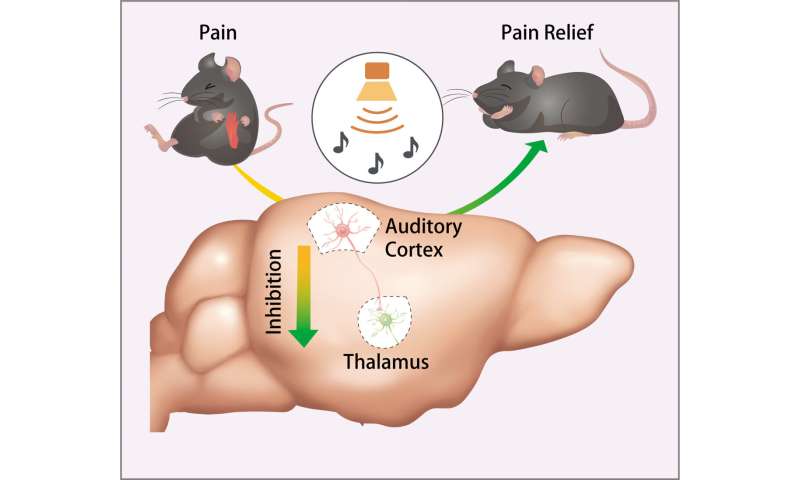

To explore the brain circuitry underlying this effect, the researchers trace connections between brain regions using fluorescent protein-tagged viruses. They identified a route from the auditory cortex to the thalamus, which relays sensory signals, including pain, from the body. In freely moving mice, low-intensity white noise reduced the activity of neurons at the receiving end of the pathway in the thalamus.

Without sound, suppressing the pathway with light- and small molecule-based techniques mimicked the pain-blunting effects of low-intensity noise, while turning on the pathway restored animals’ sensitivity to pain.

Dr Liu said it is unclear if similar brain processes are involved in humans, or whether other aspects of sound, such as its perceived harmony or pleasantness, are important for human pain relief.

“We don’t know if human music means anything to rodents, but it has many different meanings to humans – you have a lot of emotional components,” he said.

The results could give scientists a starting point for studies to determine whether the animal findings apply to humans, and ultimately could inform development of safer alternatives to opioids for treating pain.

Source: National Institutes of Health