These Newly Discovered Brain Cells Enable us to Remember Objects

Discovery of ‘ovoid cells’ reshapes our understanding of how memory works, and could open the door to new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and more.

Take a look around your home and you’ll find yourself surrounded by familiar comforts – photos of family and friends on the wall, well-worn tekkies by the door, a shelf adorned with travel mementos.

Objects like these are etched into our memory, shaping who we are and helping us navigate environments and daily life with ease. But how do these memories form? And what if we could stop them from slipping away under a devastating condition like Alzheimer’s disease?

Scientists at the University of British Columbia have just uncovered a crucial piece of the puzzle. In a study published in Nature Communications, the researchers have discovered a new type of brain cell that plays a central role in our ability to remember and recognise objects.

Called ‘ovoid cells,’ these highly-specialised neurons activate each time we encounter something new, triggering a process that stores those objects in memory and allowing us to recognise them months, even years, later.

“Object recognition memory is central to our identity and how we interact with the world,” said Dr Mark Cembrowski, the study’s senior author, and an associate professor of cellular and physiological sciences at UBC and investigator at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health. “Knowing if an object is familiar or new can determine everything from survival to day-to-day functioning, and has huge implications for memory-related diseases and disorders.”

Hiding in plain sight

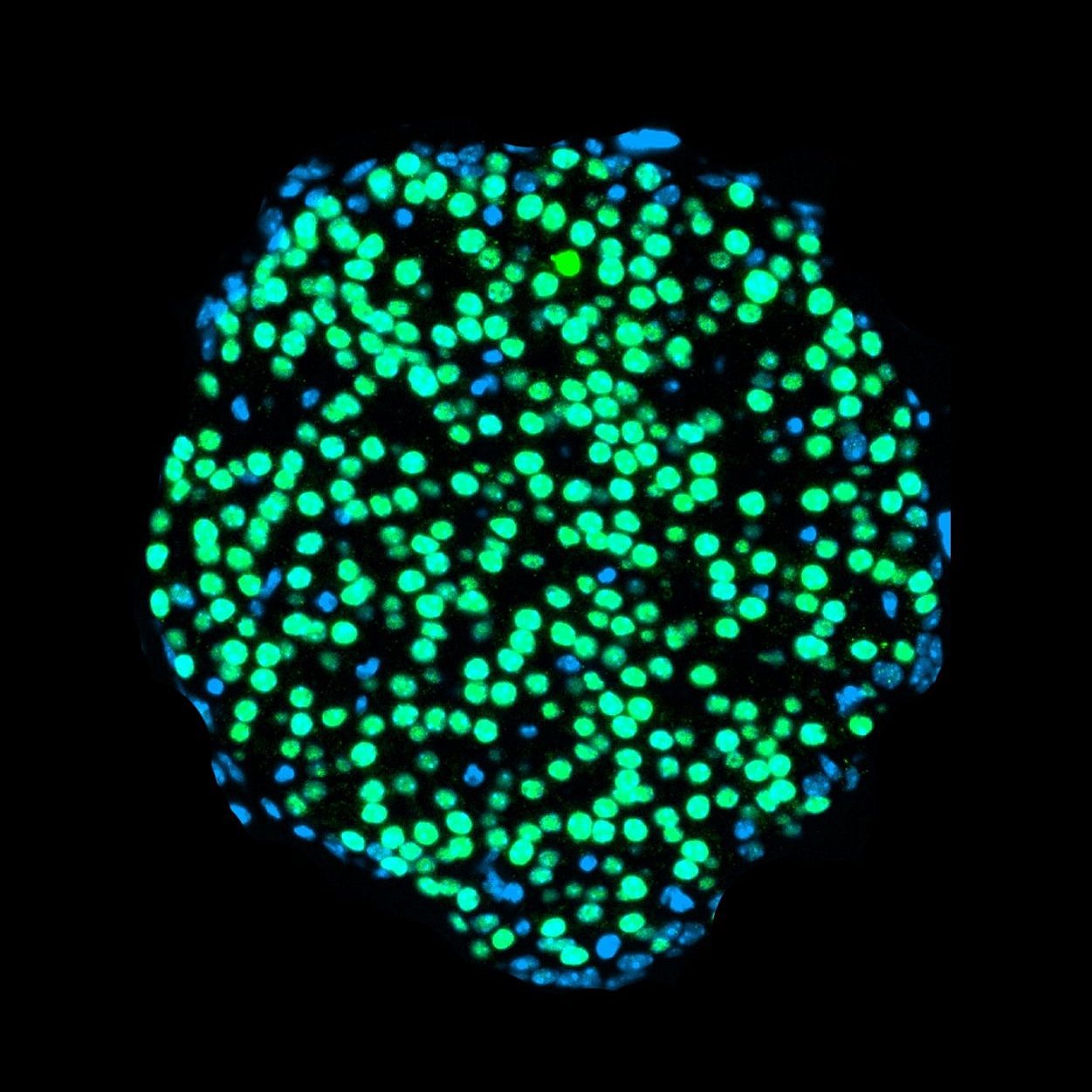

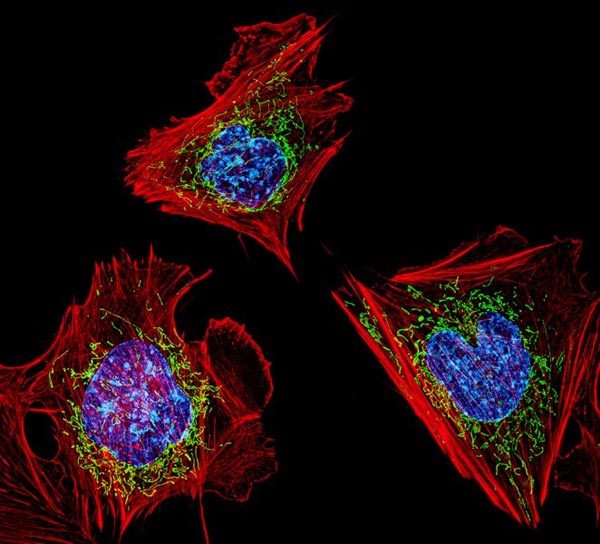

Named for the distinct egg-like shape of their cell body, ovoid cells are present in relatively small numbers within the hippocampus of humans, mice and other animals.

Adrienne Kinman, a PhD student in Dr Cembrowski’s lab and the study’s lead author, discovered the cells’ unique properties while analysing a mouse brain sample, when she noticed a small cluster of neurons with highly distinctive gene expression.

“They were hiding right there in plain sight,” said Kinman. “And with further analysis, we saw that they are quite distinct from other neurons at a cellular and functional level, and in terms of their neural circuitry.”

To understand the role ovoid cells play, Kinman manipulated the cells in mice so they would glow when active inside the brain. The team then used a miniature single-photon microscope to observe the cells as the mice interacted with their environment.

The ovoid cells lit up when the mice encountered an unfamiliar object, but as they grew used to it, the cells stopped responding. In other words, the cells had done their jobs: the mice now remembered the objects.

“What’s remarkable is how vividly these cells react when exposed to something new. It’s rare to witness such a clear link between cell activity and behaviour,” said Kinman. “And in mice, the cells can remember a single encounter with an object for months, which is an extraordinary level of sustained memory for these animals.”

New insights for Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy

The researchers are now investigating the role that ovoid cells play in a range of brain disorders. The team’s hypothesis is that when the cells become dysregulated, either too active or not active enough, they could be driving the symptoms of conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy.

“Recognition memory is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease – you forget what keys are, or that photo of a person you love. What if we could manipulate these cells to prevent or reverse that?” said Kinman. “And with epilepsy, we’re seeing that ovoid cells are hyperexcitable and could be playing a role in seizure initiation and propagation, making them a promising target for novel treatments.”

For Dr Cembrowski, discovering the highly specialised neuron upends decades of conventional thinking that the hippocampus contained only a single type of cell that controlled multiple aspects of memory.

“From a fundamental neuroscience perspective, it really transforms our understanding of how memory works,” he said. “It opens the door to the idea that there may be other undiscovered neuron types within the brain, each with specialised roles in learning, memory and cognition. That creates a world of possibilities that would completely reshape how we approach and treat brain health and disease.”

Source: University of British Columbia