Person with Tetraplegia Pilots Drone with Brain-computer Interface

A brain-computer interface, surgically placed in a research participant with tetraplegia, paralysis in all four limbs, provided an unprecedented level of control over a virtual quadcopter – just by thinking about moving his unresponsive fingers.

The technology divides the hand into three parts: the thumb and two pairs of fingers (index and middle, ring and small). Each part can move both vertically and horizontally. As the participant thinks about moving the three groups, at times simultaneously, the virtual quadcopter responds, manoeuvring through a virtual obstacle course.

It’s an exciting next step in providing those with paralysis the chance to enjoy games with friends while also demonstrating the potential for performing remote work.

“This is a greater degree of functionality than anything previously based on finger movements,” said Matthew Willsey, U-M assistant professor of neurosurgery and biomedical engineering, and first author of a new research paper in Nature Medicine. The testing that produced the paper was conducted while Willsey was a researcher at Stanford University, where most of his collaborators are located.

While there are noninvasive approaches to allow enhanced video gaming such as using electroencephalography to take signals from the surface of the user’s head, EEG signals combine contributions from large regions of the brain. The authors believe that to restore highly functional fine motor control, electrodes need to be placed closer to the neurons. The study notes a sixfold improvement in the user’s quadcopter flight performance by reading signals directly from motor neurons vs. EEG.

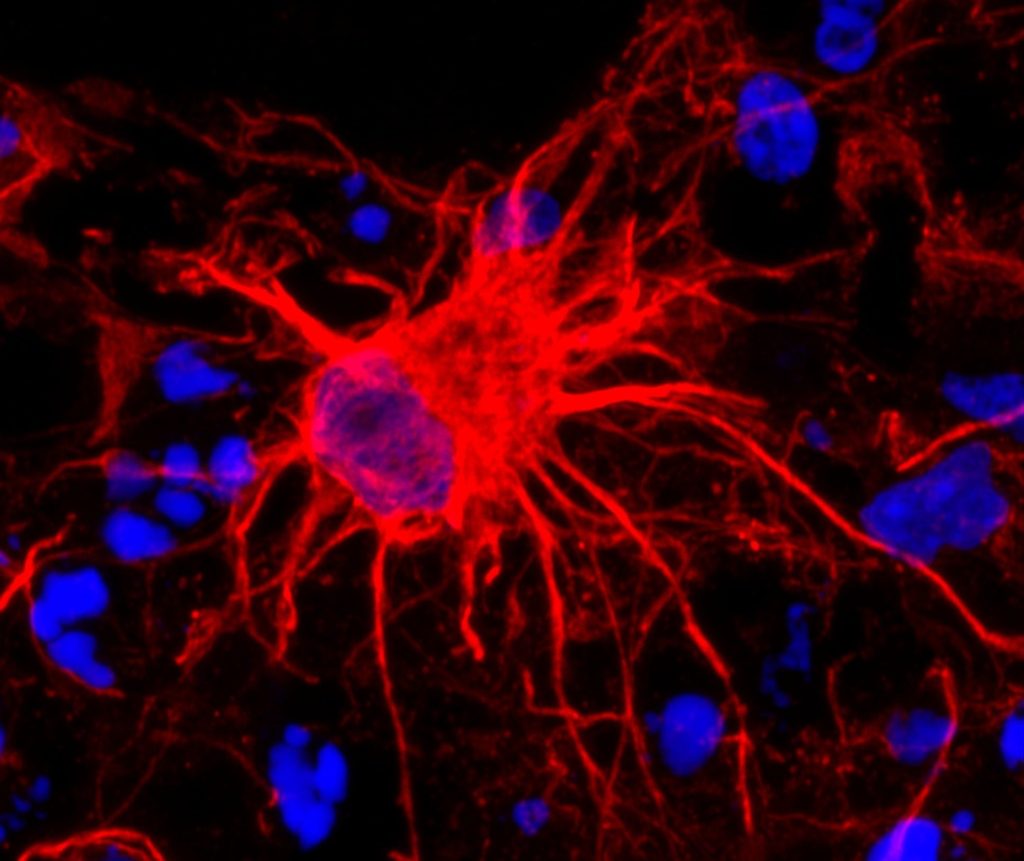

To prepare the interface, patients undergo a surgical procedure in which electrodes are placed in the brain’s motor cortex. The electrodes are wired to a pedestal that is anchored to the skull and exits the skin, which allows a connection to a computer.

“It takes the signals created in the motor cortex that occur simply when the participant tries to move their fingers and uses an artificial neural network to interpret what the intentions are to control virtual fingers in the simulation,” Willsey said. “Then we send a signal to control a virtual quadcopter.”

The research, conducted as part of the BrainGate2 clinical trials, focused on how these neural signals could be coupled with machine learning to provide new options for external device control for people with neurological injuries or disease. The participant first began working with the research team at Stanford in 2016, several years after a spinal cord injury left him unable to use his arms or legs. He was interested in contributing to the work and had a particular interest in flying.

“The quadcopter simulation was not an arbitrary choice, the research participant had a passion for flying,” said Donald Avansino, co-author and computer scientist at Stanford University. “While also fulfilling the participant’s desire for flight, the platform also showcased the control of multiple fingers.”

Co-author Nishal Shah, incoming professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rice University, explained, “controlling fingers is a stepping stone; the ultimate goal is whole body movement restoration.”

Jaimie Henderson, a Stanford professor of neurosurgery and co-author of the study, said the work’s importance goes beyond games. It allows for human connection.

“People tend to focus on restoration of the sorts of functions that are basic necessities – eating, dressing, mobility – and those are all important,” he said. “But oftentimes, other equally important aspects of life get short shrift, like recreation or connection with peers. People want to play games and interact with their friends.”

A person who can connect with a computer and manipulate a virtual vehicle simply by thinking, he says, could eventually be capable of much more.

“Being able to move multiple virtual fingers with brain control, you can have multifactor control schemes for all kinds of things,” Henderson said. “That could mean anything, from operating CAD software to composing music.”

Source: University of Michigan