Caner Signals may Promote Blood Clot Formation in the Lungs

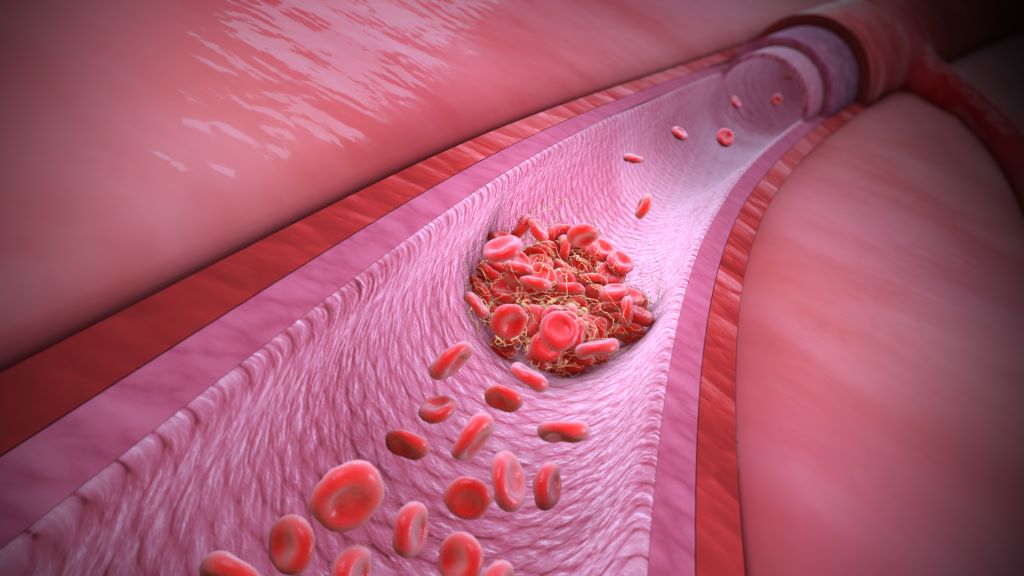

Blood clots form in response to signals from the lungs of cancer patients—not from other organ sites, as previously thought—according to a preclinical study. Clots are the second-leading cause of death among cancer patients with advanced disease or aggressive tumours.

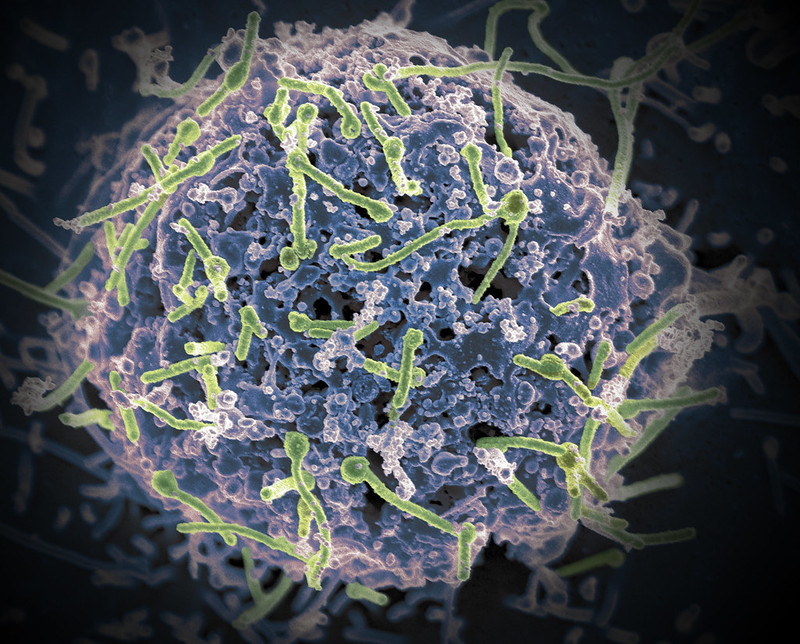

While blood clots usually form to stop a wound from bleeding, cancer patients can form clots without injury, plugging up vessels and cutting off circulation to organs. The study, published in Cell, shows that tumours drive thrombosis by releasing chemokines, secreted proteins which then circulate to the lung. Once there, the chemokines prompt macrophages to release small vesicles that attach to platelets, forming life-threatening clots.

The findings may lead to diagnostic tests to determine blood clotting risk and safer therapies that target the root of the problem to prevent blood clots.

“This work redefines the concept of how thrombosis develops in cancer patients, compared to the traditional view that factors on blood vessel walls or tumour cells themselves are responsible,” said study lead Dr David Lyden, professor in paediatric cardiology, and cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It’s a revolutionary concept that thrombosis is initiated in the lung, which wasn’t appreciated before.”

Tumors in the Driver’s Seat

“We reviewed post-mortem studies and found that up to 60% of cancer patients died because of clots rather than cancer itself,” said first author Dr Serena Lucotti, instructor of cell biology in paediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It is unfortunate because we have drugs that can prevent clots, but we can’t give them unconditionally to all patients because they can cause excessive bleeding in some. At the same time, we can’t predict who is at high risk for clots and would benefit from the drugs.”

In a series of experiments in mice and human tissues, the researchers showed that different tumours release varying amounts of the chemokine CXCL13. Breast cancers and melanomas release relatively small quantities of CXCL13. However, if these tumour cells spread to the lung, they can trigger clot formation by releasing CXCL13 and locally influencing interstitial macrophages. “In contrast, pancreatic cancer secretes high levels of CXCL13 into the bloodstream,” said Dr Lyden. “It’s so high that it circulates all the way to the macrophages in the lung, so these tumour cells don’t need to be close by.”

Blocking Clots—and Metastases

Other experiments revealed that after interacting with CXCL13, lung interstitial macrophages send out small vesicles loaded with an adhesion molecule, integrin β2, on their surface. The integrin β2 is in an open conformation that can attach to platelets and trigger clot formation.

Mice treated with an antibody that blocks vesicle-bound integrin β2 from binding to platelets had no side effects and didn’t have excessive bleeding. Strikingly, mice with early or advanced cancers that were treated with the antibody not only had fewer clots, but also had significantly fewer metastases than untreated controls. “This is important because there aren’t effective treatments for patients with metastases and will be further investigated,” Dr Lucotti said. She is developing a human antibody to block the integrin β2-platelet interaction in patients.

The researchers are also hopeful that integrin β2 can be a biomarker that indicates a patient’s risk for developing clots. As proof of concept, the team analyzed blood samples from some pancreatic cancer patients from Moores Cancer Center at the University of California San Diego Health. By analyzing blood samples collected before and after the patients experienced blood clots, the authors could easily and accurately distinguish between low-risk and high-risk patients based on integrin β2 levels on extracellular vesicles in the blood.

The study highlights that cancer is a disease that can affect many parts of the body. “Cancer is a systemic disease. We have to pay attention to not only future sites of metastasis, but other organs that may be affected independent of metastasis by systemic complications such as thrombosis, leading to morbidity and mortality,” Dr Lyden said.

Source: Weill Cornell Medicine