#InsideTheBox with Dr Andy Gray | Essential Medicines – Essential to Whom?

By Andy Gray

In the first of a new series of monthly columns for Spotlight, Dr Andy Gray considers what we mean when we refer to medicines as “essential” – something that is routinely done by the WHO and health authorities in many countries.

That every health system needs medicines, including vaccines, to treat and prevent and at times to cure diseases is obvious. However, that immediately begs a series of questions – which medicines, where, and for whom?

For nearly 50 years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has provided guidance in the form of the Model List of Essential Medicines. For almost 20 years, WHO has also provided a Model List of Essential Medicines for Children. The most recent version, issued in 2023 and due to be revised in 2025, lists over 500 medicines, including 361 specifically for children.

Those figures draw attention to a core principle that not all medicines approved by national medicines regulatory authorities, and therefore legally marketed, are considered necessary.

The WHO defines essential medicines as “those that effectively and safely treat the priority healthcare needs of the population”. It adds that the primary drivers for selecting a limited list of medicines are efficiency and effectiveness: “The use of a limited number of carefully selected medicines can lead to improved supply, better prescribing practices and lower costs.”

The initial essential medicines definition contains a highly contested component – how does one determine the “priority healthcare needs of the population”?

One element should surely be the prevalence of the condition for which the medicine is indicated. However, that alone is insufficient. The common cold is, as the name implies, ubiquitous. Should that mean that cough mixtures are essential? If the evidence of a clinically relevant health benefit from the use of cough mixtures is lacking, that should surely rule them out. The common cold is also self-limiting, without long-term consequences.

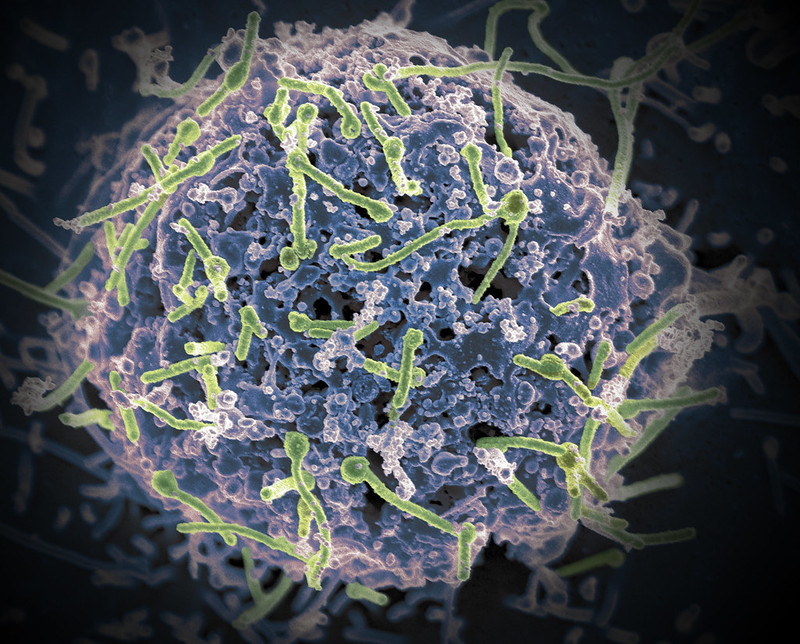

By contrast, infection with hepatitis C virus can result in serious illness and death, but also spread to others, and in some patients become a chronic disease associated with increased risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis. In that case, treating the condition not only benefits the patient, but also prevents others from being infected with the same virus. For many years, the available treatments for hepatitis C were not very effective and associated with severe adverse effects. Once new, highly effective and safer treatments became available around a decade ago, the pressure was on to consider them as essential.

That is where another part of the WHO definition comes into play: “Essential medicines should always be available within functioning health systems, in sufficient quantities to meet patient needs. They should be available in appropriate dosage forms for the intended uses and patients, be of assured quality, and be affordable for both individuals and the health system.”

But how can affordability be measured?

One approach is to consider whether the added benefits are worth the extra cost, compared to existing medicines. That approach, based on a technique called incremental cost-effectiveness analysis, does not consider the possible impact of a new medicine on the total pharmaceutical or health budget. A stunningly effective new medicine may simply be unaffordable if needed by a large number of patients, unless additional resources can be secured for the health system. In an era of fiscal restraint and shifting donor priorities, “new money” is increasingly unlikely to be found.

An even more pressing problem is posed when a new medicine becomes available that makes a significant difference to clinical outcomes, for example changing a previously fatal condition into a manageable chronic condition. The new medicine may only be needed by a few patients, but if it is very expensive it may pose a threat to available budgets and be unaffordable to individual patients and their families. Rare diseases, and the medicines to treat them, ask uncomfortable questions about how public health priorities are decided, how affordability is assessed, and how society as a whole values access to medicines. The population level perspective runs headlong into the individual.

How it works in SA

South Africa, like more than 150 other countries, has established medicines selection structures and procedures and developed a national essential medicines list (EML). The medicines selected for the EML inform the state tender system, allowing the state to use its buying power to exert downward pressure on medicine prices. Medicines procured in that way are used almost exclusively in the public sector, in health facilities operated by provincial and local government.

However, the separation between public and private sectors is not that simple. Medical schemes use similar considerations of cost effectiveness and budget impact to determine the reimbursement rules and formularies for each of their benefit options. In some cases, there are nationally-determined algorithms for specific conditions – the Chronic Disease List – that have to be covered as prescribed minimum benefits. Those algorithms have not been updated as frequently as might be desired, and certainly not as frequently as the standard treatment guidelines and EML applied in the public sector. As a result, when challenged regarding denial of coverage, the medical schemes regulator has tended to look to the state’s position as defining a standard of care. However, the reduced prices available to the state may not be accessible to the private sector.

In other words, and even before National Health Insurance is implemented, the questions of which medicines, where, and for whom remain vexing. They have to be faced, however, if any health system is to ensure the progressive realisation of the right of access to healthcare services, responsibly and effectively using the available resources.

*Gray is a Senior Lecturer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and Co-Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Pharmaceutical Policy and Evidence Based Practice. This is the first of a new series of #InsideTheBox columns he is writing for Spotlight.

Note: Spotlight aims to deepen public understanding of important health issues by publishing a variety of views on its opinion pages. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily shared by the Spotlight editors.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.