Soccer Headers may be More Damaging to Brain than Thought

Soccer heading may cause more damage to the brain than previously thought, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

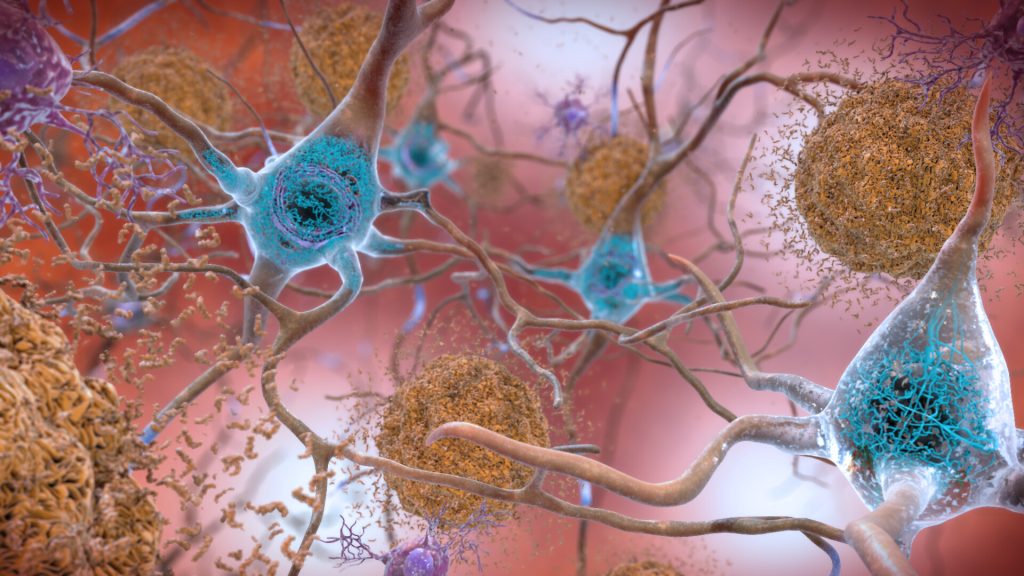

Heading is a widely used technique in soccer where the players control the direction of the ball by hitting it with their head. In recent years, research has been done that suggests a link between repeated head impacts and neurodegenerative diseases, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

“The potential effects of repeated head impacts in sport are much more extensive than previously known and affect locations similar to where we’ve seen CTE pathology,” said study senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, professor of radiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “This raises concern for delayed adverse effects of head impacts.”

While prior studies have identified injuries to the brain’s white matter in soccer players, Dr Lipton and colleagues used a new approach in diffusion MRI to analyse microstructure close to the surface of the brain.

To identify how repeated head impacts affect the brain, the researchers compared brain MRIs of 352 male and female amateur soccer players, ranging in age from 18 to 53, to brain MRIs of 77 non-collision sport athletes, such as runners.

Soccer players who headed the ball at high levels showed abnormality of the brain’s white matter adjacent to sulci, which are deep grooves in the brain’s surface. Abnormalities in this region of the brain are known to occur in very severe traumatic brain injuries.

The abnormalities were most prominent in the frontal lobe of the brain, an area most susceptible to damage from trauma and frequently impacted during soccer heading. More repetitive head impacts were also associated with poorer verbal learning.

“Our analysis showed that the white matter abnormalities represent a mechanism by which heading leads to worse cognitive performance,” Dr Lipton said.

Most of the participants of the study had never sustained a concussion or been diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury. This suggests that repeated head impacts that don’t result in serious injury may still adversely affect the brain.

“The study identifies structural brain abnormalities from repeated head impacts among healthy athletes,” Dr Lipton said. “The abnormalities occur in the locations most characteristic of CTE, are associated with worse ability to learn a cognitive task and could affect function in the future.”

The results of this study are also relevant to head injuries from other contact sports. The researchers stress the importance of knowing the risks of repeated head impacts and their potential to harm brain health over time.

“Characterising the potential risks of repetitive head impacts can facilitate safer sport engagement to maximise benefits while minimising potential harms,” Dr Lipton said. “The next phase of the study is ongoing and examines the brain mechanisms underlying the MRI effects and potential protective factors.”